Part of a series of articles titled Coastal Geohazards.

Article

Coastal Geohazards—Landslides, Slumps & Block Fall

Waves, currents, and storm surges coupled with sea level rise act to modify sediment supply along our parks’ coasts. This in turn slowly alters the morphology of coastal landforms such as bluffs. Over time, currents and waves may steepen adjacent and unconsolidated shores leading to bluff retreat and landslides (Bush & Young, 2009, Monitoring Coastal Geologic Features and Processes).

For example, nearshore currents and wind at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore carry sediment to Sleeping Bear Point where it accumulates until it becomes unstable. The sloping lakebed of Sleeping Bear Bay can tolerate only a limited amount of accumulation. When too much sand builds up, storms or saturation with melting snow can trigger a landslide. In a cycle, this process has repeated here in 1914, 1971, and again in 1995.

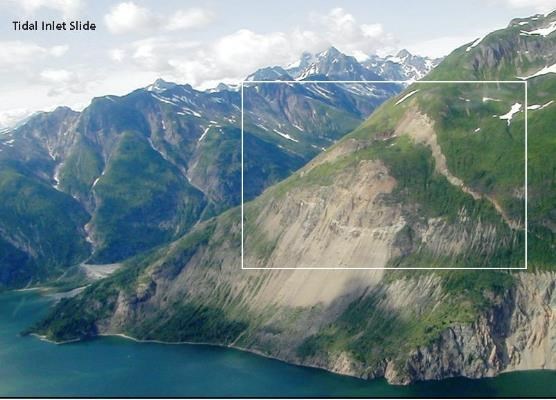

Landslides and unstable cliff faces occur throughout the Alaskan coast. They are inherently unpredictable, and major events may occur at any time. Recently released from the grip of glacial ice, this newly exposed landscape is being shaped by water, ice, gravity, as well as biological and tectonic processes. This process occurred at Taan Fiord, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve in October 2015. A mass of rock, perched 2800 ft above sea level gave way, unleashing over 150 million tons of debris. The landslide triggered a 600 ft tsunami that extended the 8-mile length of Taan Fiord and into Icy Bay. When these processes coincide with human activities they can present potential hazards to human safety. This is the case for a large landslide feature in Tidal Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park which has been creeping downslope at an average of 1.2-1.6 inches per year. If triggered, the landslide could generate a dangerous wave up to 250 feet high through Tidal Inlet and into nearby portions of Glacier Bay’s western arm, presenting a significant hazard to boaters and beach campers.

Hillslope hazards at Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore range from dramatic block falls to slower slumping. Block fall and collapse are responsible for the formation of the cliffs of Pictured Rocks. There are hundreds of block falls every year and significant events every five to seven years, typically occurring in the spring and fall due to freezing and thawing action. These block falls, although natural, are of concern to some park features. For instance, one of the two turrets at Miners Castle, a notable landmark in the park, collapsed into Lake Superior in April 2006. Like Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, many coastal locations are actively being shaped and morphed by these processes. Although natural, coastal landslides, slumping, and block fall can pose threats to our parks visitors and resources.

- Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska [Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Michigan [Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Michigan [Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

Last updated: September 10, 2018