Last updated: January 8, 2026

Article

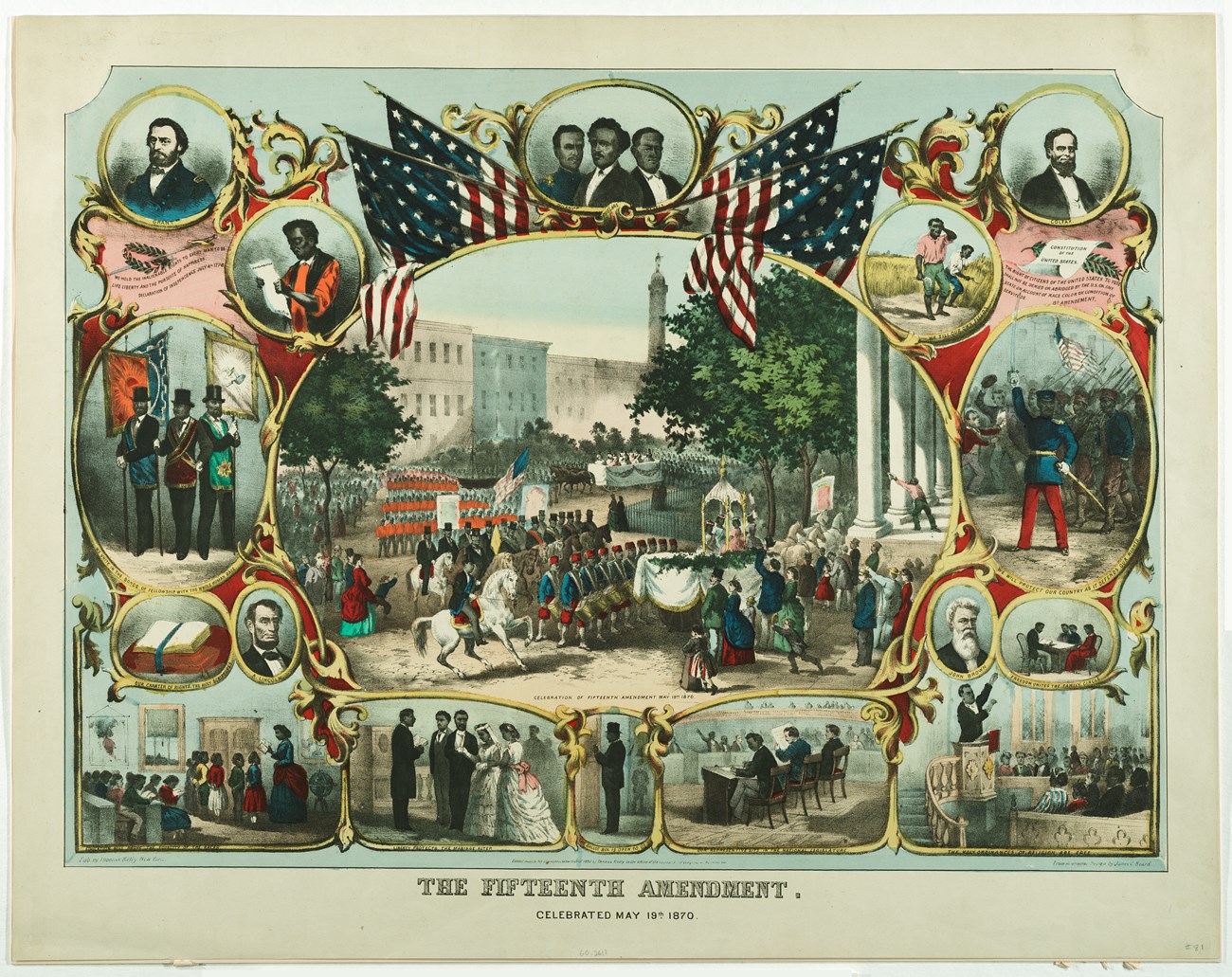

The Day of Jubilee: Celebrating the 15th Amendment in Boston

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Thus, the greatest day for the American black man, in Boston, that history has ever recorded, was Thursday, April 14, 1870. It can't be forgotten.[1]

In the spring of 1870, people gathered in massive celebrations across the United States just like the one depicted above. On April 14 thousands in Boston celebrated the ratification of the:

The words may seem simple today, but in 1870 both supporters and opponents viewed them as truly (and perhaps dangerously) revolutionary. Before the 15th Amendment, each state decided for itself who could vote. Most barred African Americans from the voting booth. Only eight states allowed unrestricted Black male suffrage. In the 1857 Dred Scott case, the Supreme Court declared that African Americans had no right to citizenship, or any other rights for that matter. Even those states which permitted Black voting were not so willing to allow African Americans a public voice. When the young Black abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond attempted to speak in Faneuil Hall in 1842, he was silenced by a wave of racist insults and threats.[2]

After the Civil War the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution (often called the Reconstruction Amendments) directly attacked that organized racial exclusion. The 13th Amendment, ratified in 1860, banned slavery in America. In 1867 the 14th Amendment overturned Dred Scott by defining birthright citizenship and granting equal rights to naturalized citizens. And in 1870 the 15th Amendment granted universal manhood suffrage. These amendments drew strong opposition. Many Americans continued to argue that Black Americans should, indeed must, be excluded from full citizenship.[3] But for the present, the cause of African American rights was victorious.

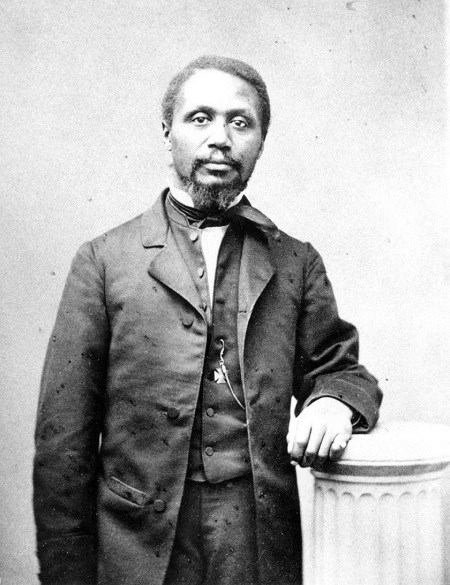

The thousands of people who gathered in Boston on April 14 celebrated that victory and trampled down that exclusion. On that day African Americans organized and led a celebration of African American citizenship, filling the public heart of Boston. Lewis Hayden, radical abolitionist and Underground Railroad operative, chaired the organizing committee. Charles Lenox Remond, once silenced in Faneuil Hall, now presided over the day. And the city and state governments not only allowed it, they gave full support. The Boston Post said it clearly, "The ratification of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution was commemorated in this city yesterday by our colored citizens."[4] [emphasis added by the author.] Nothing like it had ever before happened in Boston.

According to Black newspaperman Benjamin Roberts, the weather that day was "most beautiful." The celebration began with a grand parade in which "upwards of three thousand people" marched from Boston Common to Faneuil Hall. By the time the marchers crowded the main floor of the Hall, "the galleries were filled to their utmost capacity by an audience composed mostly of ladies." What followed was a day of great joy. Charles Lenox Remond set the tone in his opening remarks. According to the Boston Post, he said that:

…in the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment there was glory enough for one day; he could not possibly call to his lips language which would do justice to his heart or his feelings… this was the proudest day in all his experience, and he doubted not that all present felt that it was the crowning joy of our life.

Courtesy of the Social Law Library, Boston, Massachusetts.

That joy flowed from a great sense of inclusion and victory. African American attorney Robert Morris exclaimed to great applause, "Fellow citizens! How good that word sounds to-day. It is the first time I have been privileged to say that in this hall." The Boston Post reported that abolitionist and woman's rights activist William Henry Channing sounded the same note in his speech,

He said it was the first time he was ever fully at home in Faneuil Hall. He had always thought when we made the old Cradle of Liberty rock with our boasted professions of Liberty, the amens stuck in our throats. But to-day we are at home in Faneuil Hall, as one great family in the old Bay State.

Those assembled declared that victory completed, even perfected the republic. New Bedford abolitionist Rodney French said that the Civil War found "its consummation in the Fifteenth Amendment." Channing declared "the 'glittering generalities' of the Declaration of Independence, 'all men are created free and equal,' are true now." The first resolution adopted by the gathering saw the amendment as "the continuation and completion of the work commenced by the fathers of the Republic" which would lead to "the full realization of a democratic form of government, and will place our country before the nations of the earth in her true light, a living example of a great and free republic."

The celebrants did acknowledge that the nation had not yet achieved that "full realization." While the 15th Amendment guaranteed the vote for all men, women were still excluded. Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others were so angered by this that they simply condemned the amendment. Lucy Stone was one of those who took a different tact. She saw the amendment as one necessary step towards full freedom. According to the Boston Post, Stone

made a brief but spirited address, congratulating the colored citizens upon the success of their vital measure, and expressing hope for the speedy extension of the suffrage to woman. Her remarks were applauded, and a hearty 'yes' accorded to the proposition that the colored men should join hands with the women in the movement.

The celebrants also recognized that the "living example of a great and free republic" was by no means a given thing. One resolution called upon the newly enfranchised "to guard with ceaseless vigilance and jealousy the priceless boon of liberty and the valued privilege we here celebrate." That guardianship would be sorely needed. Despite Lucy Stone's "hope for the speedy extension of the suffrage," women would not win the vote for themselves until 1920. Opponents of the three Reconstruction Amendments used fraud, trickery, and open violence combined to steal African Americans' hard-won citizenship away from them. But while that call to "guard with ceaseless vigilance and jealousy" went underground it never died. It was taken up again by the physical and spiritual descendants of these 1870 celebrants as they fought to make the nation "enforce this article." The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were both the continuation and the outcome of the great struggle celebrated in Faneuil Hall 150 years ago.

Wendell Phillips gave the last speech of the day. He said that the 15th Amendment was a matter of simple justice rather than a gracious gift. He described white Americans as "Bankrupt debtors, [who] can give nothing" to African Americans. Instead, "penitent for past crimes we welcome a wronged partner to an equal share in the privileges we enjoy." For us, those words contain joy and a great challenge. Where do you see "wronged partners" struggling for inclusion today? How do you think we should respond, keeping in our minds the words of our forebears 150 years in Boston’s own "Cradle of Liberty?" We leave it to all of you to discover your own answers to those questions.

Footnotes

[1] Benjamin Roberts, “Celebration of the 15th Amendment in Boston,” The New Era (Washington, D.C.) April 28, 1870.

[2] “The Abolition Meeting in Faneuil Hall,” The Liberator, Nov. 4, 1842.

[3] For example, see “White and Black,” The Waukesha Plaindealer (Waukesha, WI), April 12, 1870, p. 2: “The alleged adoption of the 15th Amendment, is a triumph of the black race over the white…”

[4] This and all further quotations are from “The Fifteenth Amendment,” The Boston Post, April 15, 1870.