Part of a series of articles titled Suffrage in America: The 15th and 19th Amendments.

Previous: The Nineteenth Amendment

Article

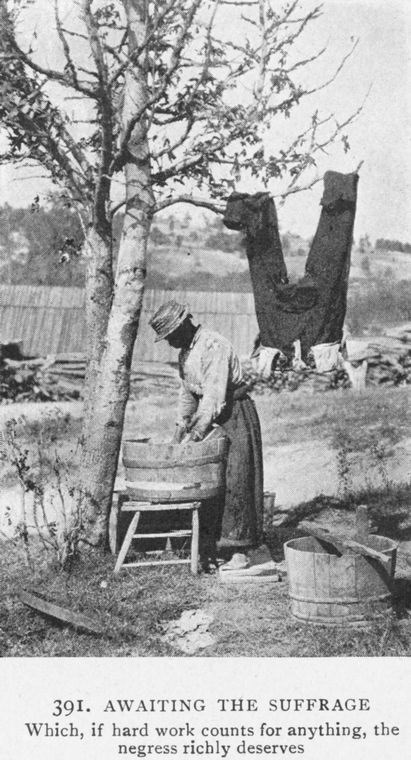

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Black women played an active role in the struggle for universal suffrage. They participated in political meetings and organized political societies. African American women attended political conventions at their local churches where they planned strategies to gain the right to vote. In the late 1800s, more Black women worked for churches, newspapers, secondary schools, and colleges, which gave them a larger platform to promote their ideas.

But in spite of their hard work, many people didn’t listen to them. Black men and white women usually led civil rights organizations and set the agenda. They often excluded Black women from their organizations and activities. For example, the National American Woman Suffrage Association prevented Black women from attending their conventions. Black women often had to march separately from white women in suffrage parades. In addition, when Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony wrote the History of Woman Suffrage in the 1880s, they featured white suffragists while largely ignoring the contributions of African American suffragists. Though Black women are less well remembered, they played an important role in getting the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments passed.

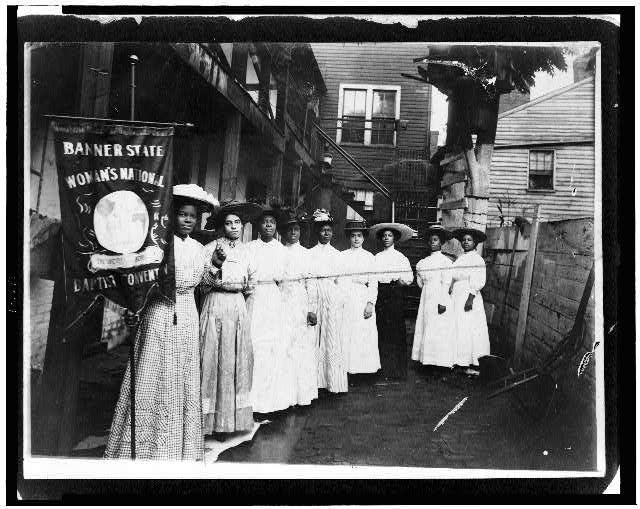

Library of Congress, Lot 12572, https://www.loc.gov/item/93505051/

Black women found themselves pulled in two directions. Black men wanted their support in fighting racial discrimination and prejudice, while white women wanted them to help change the inferior status of women in American society. Both groups ignored the unique challenges that African American women faced. Black reformers like Mary Church Terrell, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Harriet Tubman understood that both their race and their sex affected their rights and opportunities.

Because of their unique position, Black women tended to focus on human rights and universal suffrage, rather than suffrage solely for African Americans or for women. Many Black suffragists weighed in on the debate over the Fifteenth Amendment, which would enfranchise Black men but not Black women. Mary Ann Shadd Cary spoke in support of the Fifteenth Amendment but was also critical of it as it did not give women the right to vote. Sojourner Truth argued that Black women would continue to face discrimination and prejudice unless their voices were uplifted like those of Black men.

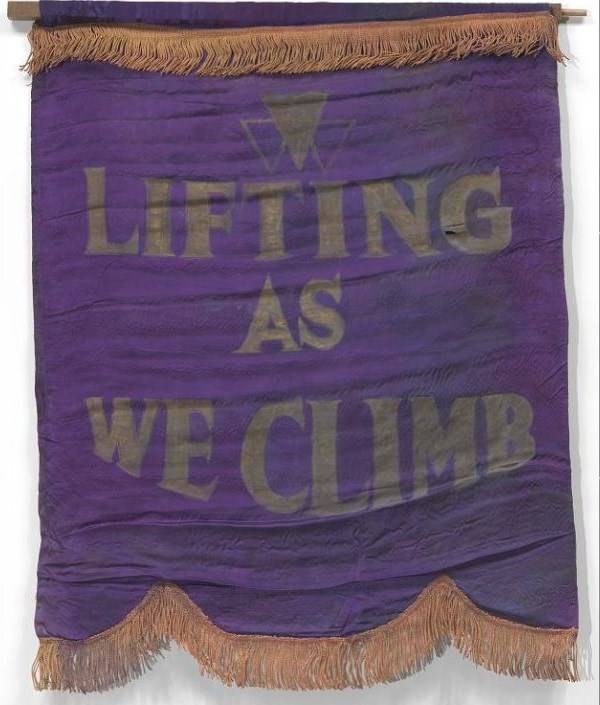

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-70ac-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a9

African American women also believed that the issue of suffrage was too large and complex for any one group or organization to tackle alone. They hoped that different groups would work together to accomplish their shared goal. Black suffragists like Nannie Helen Burroughs wrote and spoke about the need for Black and white women to cooperate to achieve the right to vote. Black women worked with mainstream suffragists and organizations, like the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

However, the mainstream organizations did not address the challenges faced by Black women because of their race, such as negative stereotypes, harassment, and unequal access to jobs, housing, and education. So in the late 1800s, Black women formed clubs and organizations where they could focus on the issues that affected them.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

In Boston, Black reformers like Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and Charlotte Forten Grimke founded the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896. During their meetings at the Charles Street Meeting House, members discussed ways of attaining civil rights and women’s suffrage. The NACW’s motto, “Lifting as we climb,” reflected the organization’s goal to “uplift” the status of Black women. In 1913, Ida B. Wells founded the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago, the nation's first Black women's club focused specifically on suffrage.

After the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920, Black women voted in elections and held political offices. However, many states passed laws that discriminated against African Americans and limited their freedoms. Black women continued to fight for their rights. Educator and political advisor Mary McLeod Bethune formed the National Council of Negro Women in 1935 to pursue civil rights. Tens of thousands of African Americans worked over several decades to secure suffrage, which occurred when the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965. This Act represents more than a century of work by Black women to make voting easier and more equitable.

LBME3-037a, Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection, 1920-1976. Photographic Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

http://digitalcollections.library.gsu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/lane/id/1580

Part of a series of articles titled Suffrage in America: The 15th and 19th Amendments.

Previous: The Nineteenth Amendment

Last updated: September 13, 2022