Last updated: August 7, 2025

Article

Wildfire and Archeology in the Jemez Mountains

This article tells the fire archeology story of the east side of the Jemez Mountains in northern New Mexico, and communicates lessons learned from over 40 years of wildfires in the area. The targeted audience is professional archeologists working in the area, but we hope it is of use to anyone wanting to learn more about fire effects and cultural resources.

Wildfire and its effects to our lives, homes, and landscapes is a shared experience by all who have lived in fire-prone areas from the earliest times through today. In the Jemez Mountains of northern New Mexico, climate change is leading to hotter summers, drought, and even more severe wildfire effects to our environment.

Scientists at the Valles Caldera National Preserve, Bandelier National Monument, and the USGS have been unravelling the story of fire history in the Jemez Mountains in order to understand the ecological processes of fire.

Learn more about the fire ecology of the Jemez Mountains in this storymap, Fire in the Jemez Mountains.

The Jemez Mountains area is a rich cultural landscape comprised of thousands of archeological sites and their related artifacts, rock art, trails, habitations, and countless other features that are vulnerable to wildland fire.

Understanding the effects of high fuel loads and the resultant high heat exposure to archeological resources during fire is one necessary step towards developing a range of climate change responses for land managers to implement on the ground.

The sections below provide links and information about a variety of investigations of fire effects to archeology and lessons learned from over four decades of fire in the Jemez Mountains.

Jemez Mountains Fire Archeology Story

Several “big fires” on the eastern side of the Jemez Mountains over the last forty years have inspired a number of studies focused on fire effects to cultural resources. We have learned through studying the history of fire in the area that these “big fires” in recent times are much bigger and more severe compared to historical fires. This is due to fire suppression management policies causing fuel build up - and due to climate change.

La Mesa Fire - 1977

La Mesa Fire in 1977 was the first time in park or forest management history that archaeologists were sent out on the fire line as part of active fire suppression. As the ~15,000 acre fire burned from June 16-23, archaeologists participated in protecting archaeological sites from damage from the fire as well as impacts from fire suppression activities. The resulting report by Traylor et al. (which was widely shared but not formally published until 1990) documented the results of post-fire surveys, the effects of the fire to masonry, ceramic, stone, and obsidian artifacts, the circumstances of damage caused by suppression activities, along with a variety of analyses including tree-rings and fire scars, ethnobotany, and dating techniques (archeomagnetic, radiocarbon, thermoluminescence, and obsidian hydration). A new term “vesiculated obsidian” was coined by Fred Trembour to describe a peculiar bubbled obsidian noted here for the first time.

The most significant legacy of the La Mesa Fire was that it not only confirmed that the presence of archaeologists in no way hindered the containment of the La Mesa Fire, it demonstrated their value and consequently provided specific recommendations and guidelines that were adopted across several agencies. La Mesa Fire also inspired two symposia; the latter in 1994 (proceedings published in 1996) has been especially influential.

- 1981 La Mesa Fire Symposium - Proceedings

- 1996 Fire Effects in Southwestern Forests: Proceedings from the Second La Mesa Fire Symposium

NPS/ K. Owenby

Dome Fire - 1996

The Dome Fire began on April 25, 1996, when an abandoned campfire on the Santa Fe National Forest flared up and then spread through the Forest to Bandelier National Monument. Strong winds, low humidity, and drought conditions caused the fire to spread quickly. Before it could be contained 10 days later, the Dome Fire burned more than 16,000 acres. Archeologists quickly mobilized to understand the impacts to archeological sites by conducting emergency excavations, survey, and erosion treatment. The Dome Fire presented an excellent opportunity for archeologists to study the effects of the fire on sites because the timing, duration, and severity of the fire was known. The Subsurface Heating Effects (SHE study) was initiated to answer a series of questions related to fire effects, the most prominent question being – how did the Dome Fire affect the subsurface component of ancestral Pueblo sites and how can we apply this knowledge for better management of sites in fire prone areas?

NPS

Conclusions from the SHE study include that under most circumstances, the Dome Fire had negligible impacts to subsurface archeological deposits and features. There was significant damage, however, when a tree or stump on or adjacent to an above ground feature burned out. In other words, if the fire was led underground by woody fuel, then the heat often caused damage to masonry and archeological deposits. The investigations after the Dome Fire led to a change in the management of archeological sites at Bandelier National Monument.

For a summary of the SHE study, see Chapter 7 of the Rainbow Series Volume, linked below.

NPS/ A. Steffen

Obsidian is a volcanic glass found in the Jemez Mountains that formed during some of the most recent vulcanism in the area (ca 1.25 mya – 15 mya). It was used as toolstone by ancestral peoples throughout the area. Immediately after the Dome Fire, archaeologists encountered a startling fire effect: obsidian in a large quarry site had been burned into frothy puffs of bubbled glass. Once it was recognized that the fire had caused this remarkable transformation of the volcanic glass, further examination at the quarry revealed several clusters of the vesiculated obsidian, as well as a wide range of other fire effects to obsidian artifacts and natural nodules at the site. Resulting research provided definitions to identify these obsidian fire effects, showed that forest fire exposure does not interfere with geochemical sourcing of obsidian artifacts but did alter obsidian hydration rinds, and investigated how intrinsic water content of obsidian in these geological deposits contributes to their susceptibility to vesiculation.

NOAA

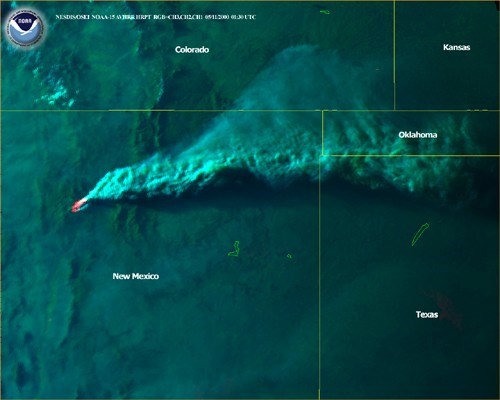

Cerro Grande Fire - 2000

The Cerro Grande Fire began on May 4, 2000 as a prescribed burn near the summit of Cerro Grande in Bandelier National Monument. Overnight, strong winds blew the fire north and east on Santa Fe National Forest lands and it was declared a wildfire on May 5. The fire continued to spread to the north and east onto Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) lands, into the town site of Los Alamos, and onto Santa Clara Pueblo lands. It burned a total of 43,000 acres, becoming the largest historically documented wildfire in the Jemez Mountains. The devastation caused by this “big fire” to homes and LANL property, as well as to the traditional gathering areas of Santa Clara Pueblo and San Ildefonso Pueblo, was unprecedented in the Jemez area. The Cerro Grande Fire resulted in sweeping changes to federal wildland fire management policy.

Locally, LANL archeologists quickly began to assess the damage and describe fire effects to archeological and historic period sites. Using lessons learned from the Dome Fire NPS emergency rehabilitation efforts, they amassed a body of data at the site scale of analysis. The archeologists' report presents summary data on the most common effects observed at Ancestral Pueblo masonry sites and described the loss of historic log cabins and features associated with late 19th and early 20th century homesteading. Importantly, members of the Pueblo of San Ildefonso and the Pueblo of Santa Clara participated in the assessment of archeological sites and other cultural resources, and later, LANL entered into contracts with Tribal crews for post fire rehabilitation and fuel management on LANL lands.

Las Conchas Fire - 2011

In 2011 the Las Conchas fire burned 156,000 acres (243 square miles). In the first 14 hours it burned more than 40,000 acres; this was nearly as many acres as had burned in what previously had been the largest documented fire in the Jemez Mountains. By the time it stopped spreading, Las Conchas fire was more than three times the size of the previous largest forest fire in Jemez Mountains history (the 2000 Cerro Grande Fire).

Check out this short video about the Las Conchas Fire.

R. Pruecel

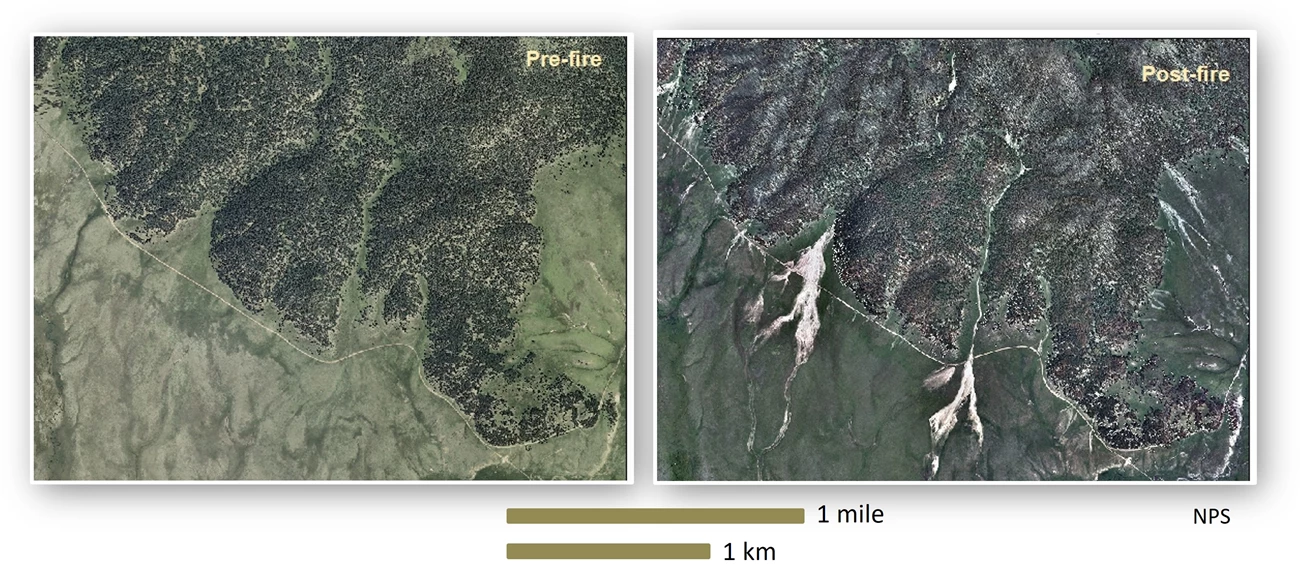

Las Conchas Fire in 2011 was a shock not only because it spread so fast and burned such a large area, but also because the severity of the fire was so high. 45% of the fire area burned with high or moderate severity, meaning that across much of the fire area all or nearly -all trees died over large contiguous areas. The resulting impacts to vegetation succession and watershed functioning were moderate to severe and in many areas significant and long-term. The fire burned a broad range of elevations (6,500 to 10,000 feet amsl) across numerous land managing agencies, including the Santa Fe National Forest, Valles Caldera National Preserve, Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico State Trust Land, and the Pueblos of Santa Clara, Santo Domingo, Cochiti, San Ildefonso, and Jemez.

NPS/ R. Schwab

Within the Las Conchas Fire area, over 2,500 documented archaeological sites were directly impacted, and when previously undocumented sites are included the total likely exceeds 3,000. These include small and large prehistoric pueblo ruins, small masonry 1-2 room “fieldhouse” sites, buried and surface artifact scatters, nearly all the large prehistoric obsidian quarries in the Jemez Mountains, the historic mining ghost towns of Albemarle and Bland, historic corrals, features built by the Civilian Conservation Corps, and a historic cemetery.

Traditional cultural places such as plant gathering areas and sacred springs were affected, causing great concern by numerous Native American pueblo communities.

NPS

By all measures, Las Conchas Fire was a worst-case scenario. At many sites within the Las Conchas Fire, the fire burned hot and long across large areas of the fire.

Ancestral Pueblo sites that burned at high intensity were left denuded of protective vegetation, with spalling masonry stones, and pottery altered and sometimes unidentifiable. Flint artifacts were cracked and crumbled.

Obsidian artifacts were shattered, splintered, and bubbled, destroying the unique potential for dating the age of the artifacts because the obsidian–hydration clock has been reset by the heat of the fire.

The vast acreage of bare, denuded upland canyonlands in the fire footprint was a looming threat to everyone located downstream, especially because the wet “monsoon” season in July was about to begin. In Frijoles Canyon, Bandelier managers recognized the potential for catastrophic flooding in the canyon; it was clear that the visitor center, part of a National Historic Landmark district, was in danger. It is located right next to Frijoles Creek and a historic motor bridge that could act as a debris dam was located directly next to it. In order to protect the Visitor Center, Bandelier managers worked with experts to rapidly document the bridge to Historic American Building Survey (HABS) standards, and then removed it with heavy equipment.

NPS

Once the summer rains arrived, a new round of destruction began. Fire damaged soils and areas without vegetation and roots repel rather than absorb the normal heavy mid-summer rains, resulting in massive surface runoff flows and flooding. Flash floods ripped through Frijoles Canyon, threatening not only the Ancestral Puebloan sites there but also the visitor center, the museum, and visitor safety. Importantly, removal of the motor bridge helped prevent the floodwaters from impacting the visitor center. Check out the 2013 flash flood in Frijoles Canyon.

Torrents of water and mud filled the water reservoirs the Pueblo of Santa Clara depended on and caused devastating and potentially permanent damage to their watershed. Check out the accounts from Santa Clara folks in the storymap, Fire in the Jemez Mountains.

Cochiti Pueblo also witnessed unprecedented flash flooding. Nearby Dixon apple orchard, known to generations of northern New Mexicans, was destroyed - a loss widely shared via a frightening video captured by P. Suina.

NPS

Over the next few seasons of rain after Las Conchas Fire, vast rock and boulder fields formed along the base of hillslopes covering archeological sites. Erosion gullies enlarged into trenches up to 20 feet wide and 12 feet deep, bisecting or washing away deeply buried sites that had previously been stable, many for several thousands of years.

NPS

Kristen Honig

Thompson Ridge Fire - 2013

Before the Jemez Mountains community had a full opportunity to grapple with the impacts of Las Conchas fire, the Thompson Ridge fire began early in the fire season at the end of May, 2013. While it was 24,000 acres in size, entirely on the Valles Caldera National Preserve, we have recently come to accept this as a fire of more “normal” size. Unlike Las Conchas, it burned with a reasonable rate of spread and expansion and resulted in a mosaic of varied fire severity. But it was unusual in that it occurred in high elevation (8,000-11,000 feet amsl) forests where normal fire return intervals are not as frequent and where the fire season usually begins later.

But even this less extraordinary “big” fire took a toll on cherished cultural resources. Atop Redondo, the forest fire burned across several features deeply significant to regional Pueblos, including the landscape eagle-image important in Jemez Pueblo cosmology and migration narratives.

Kristen Honig

Kristen Honig

The historic Baca Ranch Headquarters area burned through not once but twice. The fire fighters, aided by DC-10 aircraft fire-retardant drops, succeeded in protecting every one of the old log cabins and nearly all the majestic old-growth trees that comprise this cultural landscape. But with the onset of summer rains, erosion again wreaked havoc down the slopes, bringing down cobbles and boulders, covering roads and making them impassable. At the Baca Ranch Headquarters cabin district, the historic cabins saved from the flames were at risk from transported rock and meandering floods as La Jara Creek overflowed and threatened the the log structures. Sandbag walls were quickly constructed during post-fire burned area emergency response (BAER) to deflect the potential flooding around the historic cabins.

Kristen Honig

Understanding Archeological Fire Effects

USGS

Rainbow Series Volume

Fire archaeologists today have an excellent “go-to” reference for learning about how fire interacts with cultural resources. This is “Effects of Fire on Cultural Resources and Archaeology”, an edited volume in the Rainbow Series Wildland Fire in Ecosystem”.

The volume introduces archaeologists to the dynamics of fire behavior, and provides individual chapters each covering fire effects for prehistoric ceramics, stone artifacts, rock images, historic artifacts and features, subsurface archaeological materials, and intangible cultural resources.

The Arcburn Project

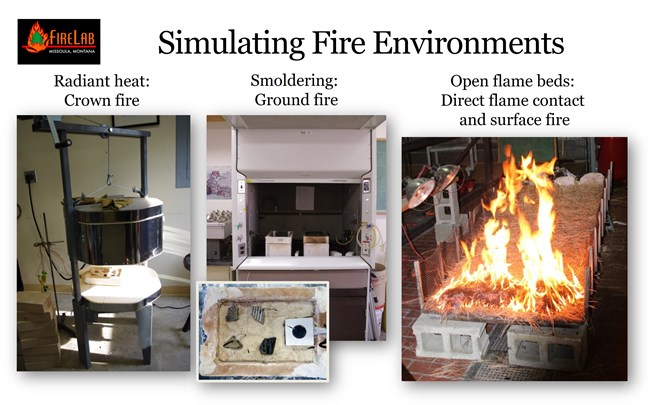

The widespread and extreme fire effects at archaeological sites in Las Conchas Fire prompted development of the ArcBurn Project, a multiagency interdisciplinary effort to quantify archaeological fire effects. ArcBurn was funded by the Joint Fire Sciences Program (JFSP). ArcBurn used controlled lab experimentation informed by fire behavior modeling to provide data on the heating intensities and durations associated with contemporary forest and woodland fuels in the Jemez Mountains.

The lab tests at the Missoula Fire Sciences Lab replicated forest fire conditions for crown fires, surface fires, and smoldering ground fires and examined the resulting effects for a suite of artifact types, including ceramics, obsidian, chert, and architectural stone (“masonry”).

Results in the final report demonstrate that the different artifact types have different responses (tolerances or sensitivity) to the three fire contexts replicated in the lab, and provide key information for resource managers seeking to manage archaeological effects of both wildfires and prescribed fires. Additional details on the experiments conducted for ceramic artifacts are available here.

Check out this online resource library for Fire and Archeology and Fire and Other Cultural Resources, compiled on the ArcBurn project website.

Preparing for More Fire using Lessons Learned

The big fires have influenced the way managers take care of the land in numerous ways. For cultural resource managers, a proactive effort to reduce fuels on the most sensitive resources has become a routine part of work. Forward thinking planning efforts also make use of data sets that have grown exponentially over the past few decades and advanced modelling methodologies that are available. Some examples of how archeologists are managing cultural resources today are included below.

Adaptive Management Responses

Lessons learned from all of the ‘big fires’ were used not only to understand the nature of fire effects to archeological materials like obsidian, masonry, and chert, but the fires also resulted in changes to managing archeological and historic sites in the Jemez Mountains.

- After La Mesa it became a more standard practice for archeologists to be part of the fire suppression response.

- Suppression impacts archeological sites and other resources became more widely known, thereby making mitigation efforts a more routine part of planning and operations.

- Bandelier managers began to routinely remove hazardous fuels off from masonry and other fire sensitive features after the Dome Fire, based the conclusions drawn from the comprehensive survey, assessment, testing, and data recovery projects conducted after the fire.

- The definition of “hazardous fuels” was refined over the years of implementing fuel reduction projects at sites in various fuel types.

- Results from ArcBurn are being used to further refine definitions of site sensitivity for management of sites during prescribed fire.

- LANL managers increased the capacity of their fuel management operations, proactively protecting historic sites with fuel breaks, and created wide fire exclusion zones along road corridors.

- The 2005 Bandelier Fire Management Plan incorporated the management response of ‘wildland fire use for resource benefit,’ one purpose of which was to use natural ignition opportunities to help reduce fuel loads on archeological sites. The archeological sites were considered included in the landscape’s fire prescription; fire was not excluded from them.

- Resource Advisors (position abbreviated as “READ”) and archeologists are included on all Bandelier and Valles Caldera wildfire response teams. Time and resources are committed so that cultural resources staff always include one or more archaeologists qualified and ready to be assigned to active fires.

- All known sites within both parks are assessed for fire sensitivity and this information is readily available during planning for managed-ignition fires (prescribed burning) and response to unplanned ignitions (wildfires).

Fuels Modeling

As part of the ArcBurn project, Friggens and others modelled fuels and other variables to predict impacts to sites. This study analyzed relationships among environmental variables and observed fire effects on archaeological sites, artifacts, and features within diverse burn areas. Results found that topographic predictors were highly important for distinguishing unburned, moderate, and high site burn severity. They conclude that models for predicting where and when fires may negatively affect the archaeological record can be used effectively to prioritize fuel treatments. Read the article, Predicting wildfire impacts on the prehistoric archaeological record of the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico.

And, check out this podcast by the Association for Fire Ecology for an interview with ArcBurn scientists about these site modeling results and the overall ArcBurn project.

Looking to the Future of Burned Landscapes

In the Jemez Mountains, the severity of fires over the past 40 years has caused long-term or permanent vegetation shifts. There are post-fire consequences to archeological sites that come with vegetation loss or shifts: erosion at a variety of scales causes destabilization of soils (e.g., the matrix of archeological deposits and foundations for buildings) and ultimately loss of information and physical structure. In many places, the forests that have existed for thousands of years, let alone our living lifetime, have changed and look and feel very different. How do we move forward?

East Jemez Landscapes Futures Collaborative

This collaborative group was formed in 2017 with the singular goal of bringing together a community of people to reckon with and address the changing post-fire and climate-change affected environment of the east side of the Jemez Mountains. East Jemez Landscapes Futures (EJLF) is a community based project that incorporates both art and science.

Begun as a collaboration with Bandelier National Monument and the USGS New Mexico Landscapes Field Station, EJLF started with a needs assessment to represent a diversity of perspectives from non-profit organizations, tribal representatives, federal, state, and local agencies, scientists, and other communities.There was time to acknowledge deep feelings of grief and a sense of uncertainty and futility or having failed to protect the lands from wildfire. Then they began building a framework for what to do in the face of the loss of a beloved landscape, and how to look forward and build new connections to an altered landscape.

See The Edge Effect, an early EJLF art project.

The collaborative works together to facilitate information sharing and decision making across jurisdictions and considers leadership from tribal partners to be an essential element to the project’s success. Through collaboration, the group focuses on concrete, action-oriented restoration strategies that are scientifically based and culturally appropriate.

Check out this 2020 webinar on the EJLF project.

The recent EJLF Restoration Strategy and Adaptation Plan explicitly applies a Resist-Accept-Direct (RAD) Framework in developing direction for recovery actions.

Additional NPS Resources

Fire and Archeology

- Fire (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

- WF: Learn about Wildland Fire - Fire (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

- Meet the Fire Scientist - Fire (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

- Video (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov) 2009, Featuring fire archeologist Jun Kinoshita

- Series: NPS Archeology Guide: Cultural Resources and Fire (this is a chapter in Archeology Guide - Archeology Program (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov), as directed by https://www.nps.gov/policy/DOrders/DOrder28A.html

- Archeology and Fire (nps.gov) Informational overview from Mesa Verde National Park.

Climate Change and Cultural Resources

- 2016 Cultural Resources Impacts Table - Climate Change (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov). Full table in this info sheet.

Website Development

This pilot version of the website was developed in advance of the symposium, "Archaeology-Climate Narratives: Science-telling for Increased Engagement", sponsored by the Committee on Climate Change Strategies and Archaeological Response (CCSAR)-sponsored Session, at the March 2022 annual meeting of the Society for American Archeology. Materials were compiled by Anastasia Steffen and Jamie Civitello, NPS. Please check back soon for further development and materials.