Last updated: July 23, 2024

Article

Theodore Roosevelt's Climate Change Legacy

Learning From the Past to Lead Us Into a Climate Resilient Future

In a world shaped by climate change, we face new challenges and threats daily. As the “conservation president,” Theodore Roosevelt also took on new ecological challenges in a rapidly changing world.

As we reflect on both the history and the future of the climate crisis, what can we learn from Roosevelt’s story? How do these lessons help us move toward a brighter future?

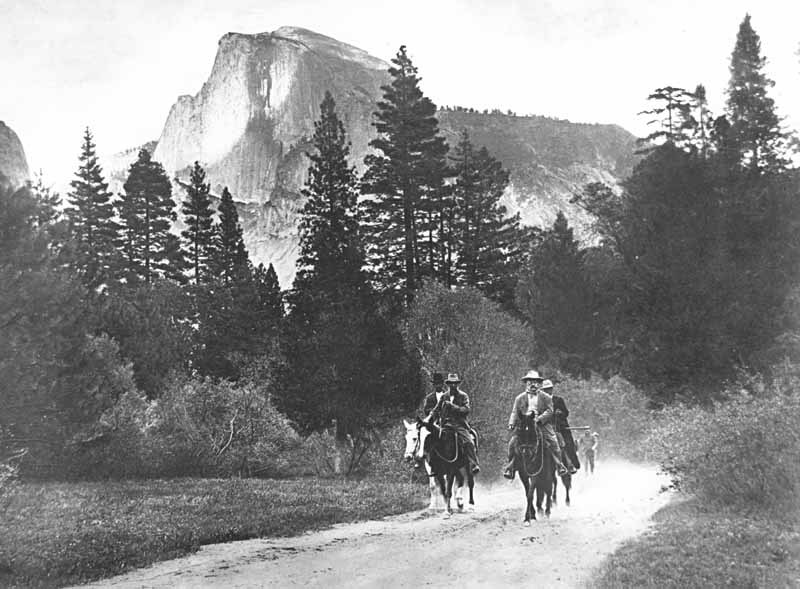

NPS Photo

“Caring about something is the first step toward caring for it.”

— National Park Service1

Roosevelt’s connection to the land sparked his passion for the environment and a whole new era of conservation in America. When a young Roosevelt lived in the North Dakota Badlands, he hunted and enjoyed the solitude the land provided. He felt so inspired that it shaped his values for the rest of his life. He wrote:

“I have always said that I would not have been President had it not been for my experience in North Dakota.”2

— Theodore Roosevelt

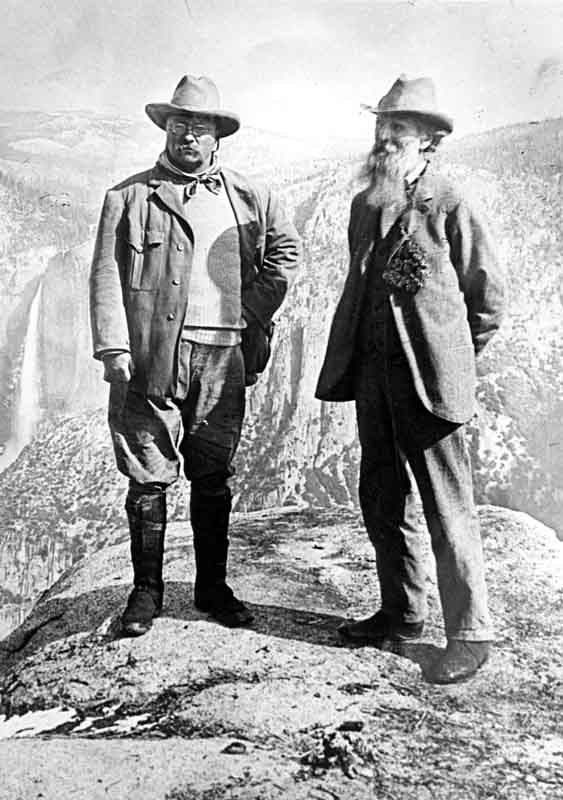

NPS Photo

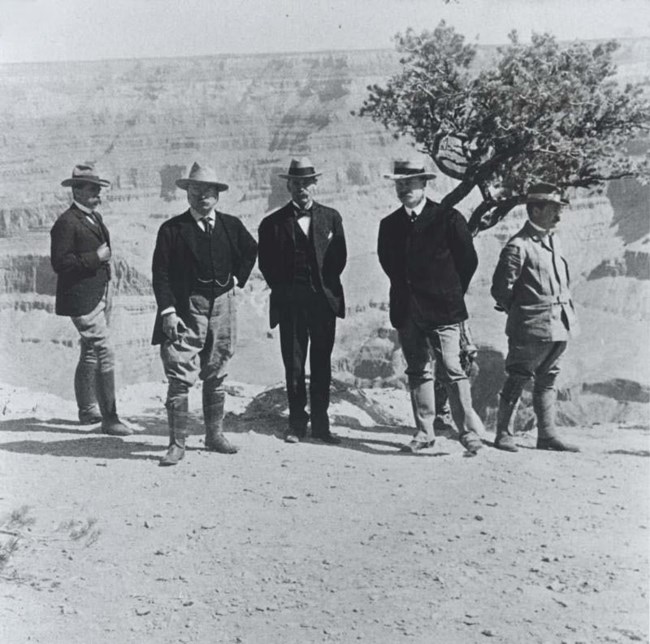

As president, he continued to find ways to connect with land. In 1903, he explored Yosemite with John Muir and visited many other sites around the country like the Grand Canyon. Roosevelt’s experiences in these parks inspired him to pass legislation preserving Yosemite, the Grand Canyon, and many other places around the country. He signed into law 228 federally preserved pieces of land.

But he didn’t do it alone. When Roosevelt was president, millions of people sent him letters and petitions asking him to protect land they loved. The influence of concerned people made it easier for him to pass conservation laws. His policies echoed the perspectives of people he heard from who were fighting for preservation. As a leader, Roosevelt responded—he used his power to translate people’s concerns into action.

Today, the impacts of climate change make Roosevelt's vision and legacy even more important. Park lands act as carbon sinks, meaning they store the carbon we release when we burn fossil fuels, which cause climate change.3 Parks also give wildlife space to adapt as climate change modifies their environment. The land Roosevelt helped conserve has given us an important tool in the fight against climate change, carrying his legacy into the future.

NPS Sean Neilson

Shifting Definitions of “Nature”

Today’s system of public lands is the result of many voices working together. But Roosevelt wasn’t listening to everyone. His vision of conservation echoed the cultural norms of the time, which disregarded Indigenous voices. Ignoring knowledge Indigenous People have developed over millennia, Roosevelt thought natural spaces had to be people-free to be “pristine” wilderness.

NPS Photo

In a speech about the Grand Canyon, he once said: “You cannot improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it.”5 To him, the only impact people could have in natural spaces was to make them worse. This was in line with his perception that wilderness was a place where people were not. And this idea is still very present today: ask the average American what wilderness is, or consult the 1964 Wilderness Act, which asserts that “man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”6

Roosevelt’s view of wilderness was in part inspired by his experience in Yosemite with John Muir. There, he encountered a landscape where the government had violently displaced and killed Indigenous People. Roosevelt’s actions as president were in line with this viewpoint, as he continued to remove Indigenous People from their ancestral homes to create protected land. Historian Theodore Catton noted that Roosevelt “targeted tribal lands for transfer to the US Forest Service... play[ing] a major role in shrinking the Indian estate” and contributed to the disintegration of tribal sovereignty.7 Roosevelt pondered that the “most ultimately righteous of all wars is a war with savages, though it is apt to be also the most terrible and inhuman.”8 He justified the cost, saying:

“I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.”9

— Theodore Roosevelt

Roosevelt violently displaced and decimated Indigenous Peoples. By doing so, he also excluded Indigenous perspectives—and limited his own view on conservation.

Why This Matters for Climate Change

NPS Photo

What Roosevelt was missing was an understanding that the land he was calling “wilderness” had been—and continues to be—stewarded by Indigenous Peoples. In the words of the 19th National Park Service director, Chuck Sams:

“Wilderness is a colonial, Western European ideal. What people call “wild,” we [Indigenous People] have called “home” for thousands of years.”10

— Chuck Sams

As a result, many Indigenous Peoples care for land in reciprocal ways using knowledge developed over millennia.

While Indigenous Peoples have integrated this knowledge into their ways of life since time immemorial, recent non-Indigenous studies have also confirmed that this works. In one 2019 study, researchers compared land managed or co-managed by Indigenous People around the world to other protected areas, like parks. They found that land with Indigenous management was just as biodiverse, if not more so, than other protected land.11 Biodiverse areas are more resilient against extreme conditions, like climate change.12 Lands managed by Indigenous Peoples have seen fewer negative impacts of climate change,12 and have been shown to store more carbon.13 With the rising challenges of biodiversity loss and intensifying climate change, it’s time to apply these practices.

What Roosevelt’s Legacy Teaches Us About Responding to Climate Change

When we recognize Roosevelt’s full legacy, we can reflect better on our own biases and legacies. In what ways do we want to be like Roosevelt? In what ways can we learn from how he caused harm?

It’s important to ask these questions so we can apply the wisdom learned from Roosevelt’s story to our response to climate change. Here are some ways we can think about applying these lessons.

-

It Takes Everyone: Roosevelt didn’t act alone. Millions of people shared their opinions and made preservation possible. In the same way, everyone has a role to play with climate change. When we all work together, we can do amazing things.

-

Conserving Land: We know that park lands—including the areas Roosevelt conserved—hold a lot of carbon. Conserved areas also act as biodiversity havens for wildlife. To respond to climate change, we’ll have to keep adding to the amount of land set aside from development. To work towards this goal, the United Nations and the Biden administration have committed to the 30 by 30 goal, which aims to conserve 30% of the world’s land and ocean by the year 2030.

-

Rethinking Our Relationship with “Nature”: Many people still see wilderness in the way Roosevelt did—thinking that people are completely separate from nature and can only hurt it. However, we know direct stewardship of the land can make it healthier. To keep both ecosystems and people resilient in the face of climate change, ideas around how we relate to nature will have to shift. That shift often starts with giving people opportunities to spend time outside, connect with land, and practice positive stewardship. It also involves adding more public land, especially in places where people have limited access to green spaces.

A 2022 intergovernmental report found that the ways that nature is valued in political and economic decisions has a big influence on biodiversity. As things are, those choices are a major driver of biodiversity loss and climate change. Shifting the way decisions are made around nature could make a significant difference in addressing both.14

Brent Johnson, NPS

-

Centering Indigenous Stewardship: It’s crucial to center Indigenous stewardship and facilitate Indigenous Peoples playing a key role in land management. At some sites, the National Park Service has begun working with Indigenous Tribes to co-steward lands and bring Indigenous practices back into park management.

For example, at Yosemite National Park, managers are working with Indigenous Peoples to bring cultural burns back to the landscape. They're collaborating with the seven traditionally associated tribes and groups, including the American Indian Council of Mariposa County, Inc. (Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation), Bishop Paiute Tribe, Bridgeport Indian Colony, Mono Lake Kootzaduka'a, North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians of California, Picayune Rancheria of the Chuckchansi Indians, and the Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indians.

The practice of cultural burning has a long history and helps ecosystems to thrive, especially in the face of climate change. In California, climate change is making wildfires more common and more intense.15 By partnering with Indigenous stewards to do proactive burns, we are creating a landscape that can thrive into the future. The very place that inspired Roosevelt can now continue to inspire us to work together for a better tomorrow.

Learning from Our History

An old saying, often attributed to Mark Twain, says “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” That is to say, things might not happen in the exact same way, but they follow familiar patterns. In order to break those patterns, we must learn from the past. That way, we can emulate it when we find things we like, and choose an alternative path when we don’t.

We have big challenges ahead of us, but history shows that we’ve risen to challenges like this before. And it shows us that when we work together, we can make a meaningful difference.

As you think about this, what ideas come to mind? How can you learn from Roosevelt’s legacy? Think about ways you do and don’t want to follow in his footsteps—and ways you can put those values into action in your life and community.

NPS Photo; Connar L'Ecuyer

Looking to take action? Here are some ideas:

-

Nurture your connection to land however works best for you. Then, take an active role in stewarding those places by volunteering, advocating for their protection, and sharing them with your loved ones.

-

Learn about the history of places you’re in—especially of the Indigenous Peoples there. Center Indigenous stewardship practices in your interactions with land, as much as you can.

-

Join a local climate action group.

-

Talk to people in your community about climate change and Roosevelt’s story. Your voice has an impact—especially with people you know!

-

Be an active citizen and share your opinions with your representatives—as millions did to encourage Roosevelt to take action.

-

Reduce your carbon footprint, and talk about what you did with your friends and family. Maybe they’ll be inspired to do the same!

1. National Park Service. 2007. Foundations of Interpretation Curriculum Content Narrative. https://www.nps.gov/idp/interp/101/foundationscurriculum.pdf

2. National Park Service. n.d. Theodore Roosevelt Quotes. https://www.nps.gov/thro/learn/historyculture/theodore-roosevelt-quotes.htm

3. Banasiak, Adam, Linda J. Bilmes, and John Loomis. 2015. "Carbon Sequestration in the U.S. National Parks: A Value Beyond Visitation." Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper Series. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/carbon-sequestration-us-national-parks-value-beyond-visitation

4. National Park Service. Updated 2024. Roosevelt Point. https://www.nps.gov/places/000/roosevelt-point.htm

5. National Park Service. 2017. Theodore Roosevelt and Conservation. https://www.nps.gov/thro/learn/historyculture/theodore-roosevelt-and-conservation.htm.

6. United States Congress. 1964 Wilderness Act. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/wilderness/upload/W-Act_508.pdf

7. Miller, Char, and Clay S. Jenkinson. 2020. Theodore Roosevelt, Naturalist in the Arena. University of Nebraska Press.

8. Roosevelt, Theodore. 1906. The Winning of the West, Volume 3.

9. Hagedorn, Hermann. 1921. Roosevelt in the Bad Lands, Volume 1. Houghton Mifflin.

10. Sams, Charles "Chuck", interview by High Country News. 2022. From dominance to stewardship: Chuck Sams' Indigenous approach to the NPS (November 1). https://www.hcn.org/issues/54.11/indigenous-affairs-national-park-service-from-dominance-to-stewardship-chuck-sams-indigenous-approach-to-the-nps

11. Schuster, Richard, Ryan R. Germain, Joseph R. Bennett, Nicholas J. Reo, and Peter Arcese. 2019. "Vertebrate biodiversity on indigenous-managed lands in Australia, Brazil, and Canada equals that in protected places." Environmental Science & Policy 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.07.002

12. The 2022 Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services report states, “in many regions… the lands of indigenous peoples are becoming islands of biological and cultural diversity surrounded by areas in which nature has further deteriorated.”

For more, see:

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Key Messages from the IPBES Global Assessment of particular relevance to Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. 2019. https://files.ipbes.net/ipbes-web-prod-public-files/inline- files/ILK_KeyMessages_IPBES_GlobalAssessment_final_ENGLISH_lo-res.pdf

13. Walker et al. 2020 says “Overall, [Indigenous Territories] (excluding [Indigenous Territory/Protected Natural Area] overlap) had the highest carbon density of any land category” (page 3022).

See: Walker, Wayne S., Seth R. Gorelik, Alessandro Baccini, Jose Luis Aragon-Osejo, Carmen Josse, Chris Meyer, Marcia N. Macedo, et al. 2020. “The role of forest conversion, degradation, and disturbance in the carbon dynamics of Amazon indigenous territories and protected areas.” PNAS. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1913321117

14. Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. 2022. Media Release: IPBES Values Assessment - Decisions Based on Narrow Set of Market Values of Nature Underpin the Global Biodiversity Crisis. July 10. https://www.ipbes.net/media_release/Values_Assessment_Published.

15. Gutierrez, Aurora A., Stijn Hantson, Baird Langenbrunner, Bin Chen, Yufang Jin, Michael L. Goulden, and James T. Randerson. 2021. "Wildfire response to changing daily temperature extremes in California's Sierra Nevada." Science Advances. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abe6417