Last updated: December 8, 2021

Article

The Superpower of Singing: Music and the Struggle Against Slavery

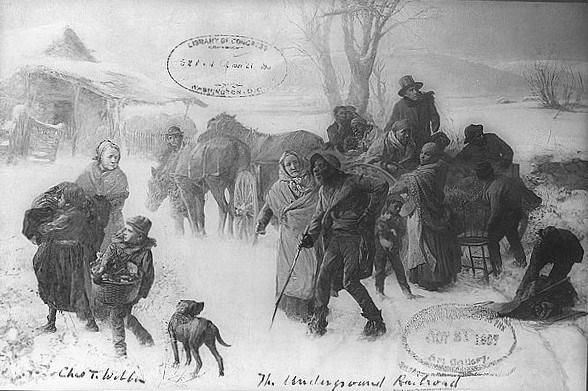

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

When spoken words are impossible or inadequate vessels, singing is a superpower, resonating through the body, shifting the atmosphere, and communicating beyond the words. This superpower was critical to Africans enslaved in the United States. They found solace and strength in African song as well as songs birthed from the trauma of chattel slavery. Through forceful removal from Africa, the dangerous middle passage, to inhumane treatment on the plantation, song served important purposes including recreation, prayer and worship, and work songs or field hollers. Beyond the musical aspects, singing provided religious and social commentary. All were cultural repositories connecting people from various African tribes. As Folklorist, Ralph Metcalfe observed, music is and was one of the most stable aspects of West African culture because of a reasonably cohesive musical system and the function of music at the core of African society.[1] For Frederick Douglass, the deep, soul-stirring singing he grew up hearing “was a testimony against slavery and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains….. To those songs I trace my first glimmering conceptions of the dehumanizing character of slavery.”[2]

Because of its association with resistance, slaveholders attempted to destroy African culture, yet resilience and creativity persisted. After the 1739 Stono Rebellion[3] in South Carolina, drums, considered dangerous communication tools, were prohibited.[4] Unfazed, the rhythmic power transferred to the body and voice. Singing also played an important role in the quest for freedom. The Underground Railroad, defined by the Network To Freedom Program as “resistance to enslavement through escape and flight,”[5] was dangerous for everyone involved, including those who assisted.

-

Music and the Underground Railroad: Talking Drum

Many people attempted to regulate the expression of those they enslaved. For example: some socieities banned the use of drums, which could be used as a means of communication that enslavers often could not understand. Despite this: Black creativity and expression persisted. In this video, musician Bruce Barnes shows us how a talking drum, used in some Nigerian societies, was used to communicate.

- Duration:

- 2 minutes, 6 seconds

-

Music and the Underground Railroad: the Hand Drum

African American communities used music and song, sometimes in place of written communication, to discuss life, death, spiritual philosophies, and emotions: all of which helped individuals cope with the traumas that came with being enslaved. In this video, musician Bruce Barnes sings "Brotherly John is Gone" while playing an African hand drum to illustrate one way song was used for self expression.

- Duration:

- 4 minutes, 43 seconds

Library of Congress Photographs and Prints Division

Being able to carry messages without suspicion was critical. Since most enslaved were illiterate, singing was a powerful tool. Sarah Bradford in her 1886 book, Harriet, The Moses of Her People, explains how Harriet Tubman conveyed “something more than met the ear” to friends the night she planned her escape. With surreptitious looks Harriet sang, "When dat ar ole chariot comes I'm gwine to lebe you, I'm boun' for de promised land. Frien's, I'm gwine to lebe you… Farewell ! … I'll meet you in de mornin'… when you reach de promised land on de oder side of Jordan, for I'm boun' for de promised land."[6] For some, Jordan meant heaven, but for Harriet and many others it declared “a speedy pilgrimage toward a free state, and deliverance from all the evils and dangers of slavery."[7]

-

Music and the Underground Railroad: Harmonica and Washboard

In Africa, people often used coded language in music. This tradition continued in communities of African descent in the United States. This coded language in music provided people with an outlet to discuss topics of social justice, political philosophy, or even express emotions that would otherwise be frowned upon by enslavers and people who sympathized with the institution of slavery. In this video, musician Bruce Barnes sings the song "Run Mary Run (You've Got the Right to the Tree of Life)."

- Duration:

- 4 minutes, 12 seconds

Resistance took many forms. For some, choosing not to attempt physical escape meant finding freedom in other ways. Singing was the superpower that freed their souls. It reaffirmed their ‘somebodiness’ in a world that treated them like animals. Just as some chose the dangers of the Underground Railroad or the perils of remaining, others took advantage of natural resources and unexpected alliances. In Louisiana, escaping Africans commonly went into the Native American-based bayou cypress swamp camps where they lived as Maroons (uncaught runaways) and waged guerilla warfare against slaveholders. Similarly, those in southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina built communities in the Great Dismal Swamp.[8] Songs in these communities maintained African musical aesthetics while blending diverse traditions with stories of flight, struggle, hope, and justice.[9]

-

Music and the Underground Railroad: Tambourine

In Louisiana, enslaved and free Black Americans met once per week in Congo Square, or Place de Congo, to express themselves through song and dance. The legacy of the kinds of music they created then still exists today, in Gospel music and spirituals. Our final video shows musician Bruce Barnes singing "Got on my Rockin' Shoes in the Morning (Hallelu, Hallelu)."

- Duration:

- 4 minutes

-

Music and the Underground Railroad: Mules Jawbone

All people can feel the power of music, regardless of where you are from or what language you speak. The international slave trade transported African people all over the world. Africans passed their cultural traditions to their children, and as a result, African influence can be seen in cultures all around the world. In this video, musician Bruce Barnes sings a song in Louisiana Creole - a unique language native to Louisiana which was heavily influenced by French and African languages.

- Duration:

- 3 minutes, 19 seconds

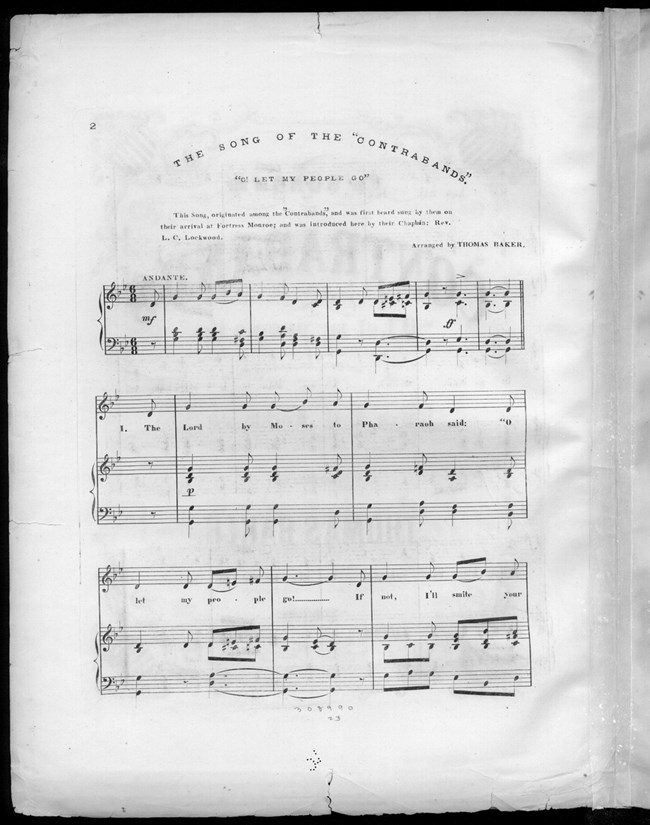

Library of Congress Photographs and Prints Division

Library of Congress

While the country was enmeshed in the Civil War, the music kept playing. In 1861 three freedom seekers, Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory, and James Townsend, boldly sought refuge at the Union Army’s Fort Monroe and were declared “contraband of war.” Their bold act of resistance opened the floodgate. Between four and five hundred thousand formerly enslaved individuals fled to Union-occupied areas, where they lived and worked as “refugees” in contraband camps. In these camps, two streams of singing existed. The formerly enslaved continued to sing spirituals as they navigated the gray area between slavery and freedom. It was not unusual to hear voices plaintively singing, There is a balm in Gilead to make the wounded whole; there is a balm in Gilead to heal the sin-sick soul at the Mansion House Hospital, the Union military hospital in Alexandria.[10] At the same time, contraband songs emerged.[11] A chaplain at Fort Monroe, Rev. L.C. Lockwood, wrote down the words and music for “Go Down Moses” which arranger Thomas Baker used as the basis for his 1861 publication.[12] Baker noted in the music score that freedom seekers were singing it as they approached Ft. Monroe. Yet, the phrase, let my people go, was extracted and became an emancipation slogan for rallies. Contraband songs, though rooted in slave culture, even borrowing slave “voice,” were mostly created by Northern Whites. These detached creations, which circulated widely in both the north and south, were used by both sides for their competing political and ideological purposes.

The power of singing and collaborative resistance are superpowers that we, in the 21st century, would do well to remember as we pursue the full realization of freedom and justice for all. The fight belongs to everyone, people of different races and faiths working together and singing with one voice.

This article was contributed by Rev. Dr. Donna Cox.

Footnotes

[1] Ralph H. Metcalfe, "The Western African Roots of Afro-American Music," The Black Scholar 1.8 (1970): 17, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41206250.

[2] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself, edited by Benjamin Quarles (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, [1845]1960), 99.

[3] Claudia Sutherland, “Stono Rebellion (1739),” Black Past.org, September 18, 2018, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/stono-rebellion-1739/.

[4] Banning of drums was not consistent throughout young America. African drumming continued unabated in places like Congo Square in New Orleans. See Drumming for Peace, “African Drumming in Early America (Part 1),” Drumming for Peace, January 1, 1970, http://drummingforpeace.blogspot.com/2009/02/african-drumming-in-early-colonial.html.

[5] “What Is the Underground Railroad?,” National Parks Service (U.S. Department of the Interior), https://www.nps.gov/subjects/undergroundrailroad/what-is-the-underground-railroad.htm.

[6] Bradford, Sarah (1886). Harriet The Moses of Her People, Lockwood & Son, NY. 28

[7] Douglass, An American Slave, 98.

[8] Archaeologist Daniel Sayers has explored and written about many of the remaining 112,000 acres of swamp and shares his discoveries. See Sandy Hausman, “Fleeing To Dismal Swamp, Slaves And Outcasts Found Freedom,” NPR (NPR, December 28, 2014), https://www.npr.org/2014/12/28/373519521/fleeing-to-dismal-swamp-slaves-and-outcasts-found-freedom#:~:text=Most%20Americans%20know%20about%20the%20Underground%20Railroad%2C%20the%20route%20that,Virginia%20and%20northeastern%20North%20Carolina.

[9] Communities of people of African descent not born on the continent have been formed with the intention of reclaiming what was lost in the middle passage. They continue to create new songs using African languages even as the members attempt to learn to speak different African tongues

[10] Kenyatta D. Barry, “Singing in Slavery: Songs of Survival, Songs of Freedom,” PBS (Public Broadcasting Service), http://www.pbs.org/mercy-street/blogs/mercy-street-revealed/songs-of-survival-and-songs-of-freedom-during-slavery/.

[11] Michael Cohen has written a rich article on the social history of contraband song. See Michael Cohen, “Contraband Singing: Poems and Songs in Circulation During The Civil War,” American Literature 82. 2 (2010): 271-304.

[12] Sacvan Bercovitch and Cyrus R. K. Patell, eds, Nineteenth-Century Poetry, 1800-1910, Vol. 4 (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 202; “Image 2 of The Song of the Contrabands,” The Library of Congress, accessed June 10, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/resource/ihas.200001991.0/?sp=2. The song was arranged by Thomas Baker and published by Horace Waters, New York, 1861.

Additional Reading

Cox, Donna M. “The Power of a Song in a Strange Land.” The Conversation, September 3, 2020. https://theconversation.com/the-power-of-a-song-in-a-strange-land-129969.

Tags

- music

- black music month

- african american culture

- underground railroad

- network to freedom

- ugrr

- women's history

- african american history

- african american history and culture

- music history

- arts culture and education

- women and the arts

- cultural history

- slavery

- slavery and abolition

- singers

- singer

- performing arts