Last updated: January 8, 2026

Article

Charles Street Meetinghouse: Historic Safe Haven for Radical Thinkers

Boston Public Library

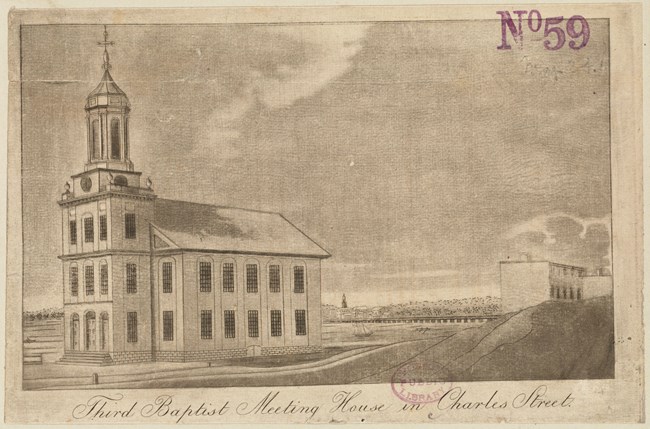

Located on the corner of Mt. Vernon and Charles Streets since 1807, the Charles Street Meetinghouse served as a home to several different communities over the past 200 years.[1] Over the course of its existence, the Meeting House became a platform and safe haven for some of Boston’s radical thinkers.

The Third Baptist Church, the original congregation of the Meetinghouse, embodied the traditional New England mindset of the early 1800s. As a segregated church, White members owned pews and forced their Black peers to sit in the galleries above.

In 1836, congregation member Timothy Gilbert challenged this segregated practice and invited several of his Black peers to join him in the pew that he owned. In response, the church congregation kicked Gilbert out, who elected to form his own church, Tremont Temple. Tremont Temple became the first church in Boston to abolish the practice of buying pews.[2] Although this original congregation rejected the radical actions of Gilbert, he stood as one of the first radical thinkers of the Charles Street Meetinghouse, using his voice to advocate for change.

When the First African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) bought the Meetinghouse for $40,000 in 1876, they transformed it into a church led by Black people for Black people. These Black Bostonians created a thriving community that welcomed new thinkers and radical ideas.[3]

The AME at the Charles Street Meetinghouse hosted events that defined the building as a safe space. In 1895, the First National Conference of Colored Women of America held a special session at the Meetinghouse to form the National Federation of Afro-American Women.[4] The Conference consisted of Black women from across the country seeking to organize a movement of Black clubwomen with shared goals. The Meetinghouse gave them space to discuss and promote their groundbreaking plans.

The AME Church moved to Boston’s South End in 1939 as the population of Beacon Hill began to change. The Charles Street Meetinghouse stood as the last Black institution to leave Beacon Hill, outlasting both the African Meeting House and Twelfth Baptist Church[5] For the duration of the AME’s time in the Meetinghouse, it provided a home to a thriving community of radical thinkers. This legacy continued into the twentieth century as the Charles Street Meetinghouse became a safe space for the gay community.

The Charles Street Meetinghouse first gained recognition for its historic value after the AME congregation left. Following the change in congregation, the Charles Street Meetinghouse Society purchased the Charles Street Meetinghouse. Shortly after, in 1947, the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (today known as Historic New England) acquired it through a grant.

Following the departure of an Orthodox Armenian congregation in 1949, it served as a Universalist Church, and in 1960, it became a Unitarian Universalist Church.

Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections

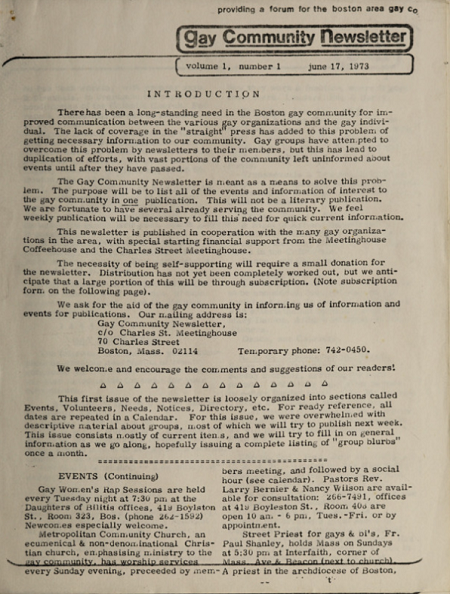

Reverend Randall Gibson, who joined the Unitarian Universalist Church at the Charles Street Meetinghouse in 1968, welcomed a new congregation and new ways of thinking.[6] Characterized as experimental and radical, the new congregation welcomed the gay, lesbian, and bisexual community. Under Gibson’s leadership, the Meetinghouse hosted Boston’s first gay dance in 1970. At the time, two people of the same gender were not allowed to dance together at bars.[7] Unfortunately, organizers cancelled the next gay dance scheduled at the Meetinghouse due to pressure from Mayor Kevin White. Despite these setbacks, the Charles Street Meetinghouse became synonymous with radical acceptance. The Meetinghouse hosted events such as poetry nights, film showings, athletic organizations, Pride planning, dances, and victory celebrations for Elaine Noble, the first elected openly Lesbian politician in Boston.[8]

The Unitarian Universalist Church at the Charles Street Meetinghouse continued to substantially support the gay community by housing Gay Community News, the first newspaper for the gay community that served the Boston area. With support from the community, Gay Community News grew from a 4 page newsletter shared only in Boston to a 16 page newspaper circulated throughout New England.

"Seven Hired to Help Gay Youth," Gay Community News vol. 2, no. 32 (February 1, 1975), Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

In 1973, at the time of the creation of Gay Community News, a rise in anti-gay crimes and moral panic made life difficult for the gay community. During its first year, Gay Community News found refuge in the Charles Street Meetinghouse. After Gay Community News relocated in 1974 to 22 Bromfield Street, the Meetinghouse kept providing a safe space for the gay community to thrive. Similarly to its time as the AME, the Meetinghouse’s congregation continued to advocate for the community it served. In 1974, Rev. Gibson created Project Lambda, a gay youth advocacy group and the first of its kind to be nationally funded. The “Youth Advocacy Commission of Treatment Alternatives to Street Crime-Juvenile” awarded this program $52,371 to fund ongoing programming for the gay youth community.[9] Project Lambda hired young adults to act as mentors, host events, and help cultivate a sense of community for the gay youth at the Charles Street Meetinghouse.

Since 1807, the Charles Street Meetinghouse evolved from a segregated church to a safe space for those traditionally unwelcome elsewhere in society. While the first congregation rejected Timothy Gilbert for striving to integrate the church, the later AME congregation endured as a Black institution on Beacon Hill. In the 1970s, it transitioned into a safe space for the gay, lesbian, and bisexual community, hosting the first gay dances and gay youth advocacy programs in Boston. In 1973, Gay Community News reflected, “But the fact remains that CSMH is not a Gay Community Center, and in fact, not even a gay church. Our usage of the church is part of an historical progression, with another group filling our place as soon as we depart and further fulfilling the Meetinghouse’s historical role.”[10] Today, the Charles Street Meetinghouse stands as a witness to these communities through its recognition on the National Register of Historic Places and its inclusion on the Black Heritage Trail®.

Footnotes:

[1] The Charles Street Meetinghouse has been spelled a few different ways over the course of its history. This article will be using the one word ‘Meetinghouse’ spelling based on the Gay Community News articles.

[2] “Tremont Temple,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/places/tremont-temple.htm.

[3] Kathryn Grover and Janine V. da Silva, "Historic Resource Study Boston African American National Historic Site," (2002), 118-119.

[4] “Charles Street Meeting House,” Boston African American National Historic Site.

[5] “Charles Street Meeting House,” Boston African American National Historic Site.

[6] “Meetinghouse Receives Grant,” Gay Community News, November 2, 1974, Volume 2 Number 19A, https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/files/neu:m046dx60z.

[7] “Boston and Stonewall 50: Remembering, Celebrating, and Honoring Our Past,” The History Project and Mass Cultural Council, 2019, https://uploads.knightlab.com/storymapjs/72526841f2384b2f30c3b514a37d4887/boston-stonewall-50-commemoration-locations/index.html;

“Love Is All You Need, 1970,” Documented | Digital Collections of The History Project, accessed August 25, 2021, https://historyproject.omeka.net/items/show/879.

[8] “Greetings” Gay Community News, October 5, 1974, Volume 2 Number 15, accessed August 2021, https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/files/neu:m046gk390.

[9] “Meetinghouse Receives $52,371,” Gay Community News, December 21, 1974, Volume 2 Number 26, accessed August 2021, https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/files/neu:m046gk586.

[10] “React,” Gay Community News, July 26, 1973, Volume 1 Number 6, https://repository.library.northeastern.edu/files/neu:m046dx71g.