Last updated: September 22, 2023

Article

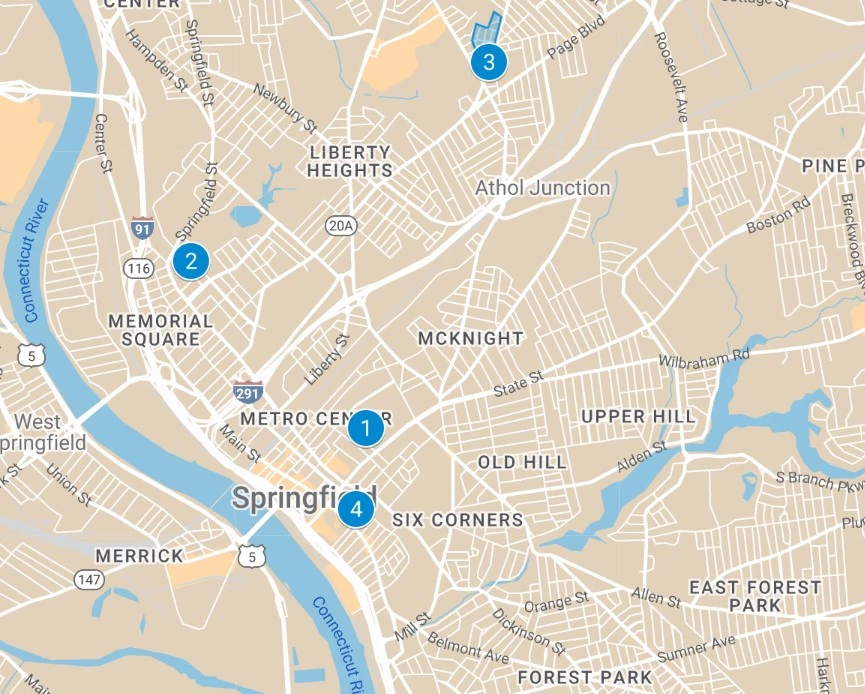

Places of World War II History in Springfield, MA

© 2008-2023 TownMapsUSA.com

The city of Springfield, Massachusetts has a history of contributing to America’s military efforts, including World War II. Designated by George Washington, the Springfield Armory is the United States’s first national armory. It produced several models of rifles during World War II. The Armory employed 13,500 people during the war, 43% of whom were women. Springfield residents also worked in factories, producing other war-time necessities; and in hospitals, training to be nurses and doctors abroad. Segregated working and living conditions led to racial tension in the city and protests from the African American community.

The Secretary of the Interior designated Springfield an American World War II Heritage City in December 2022.

This article showcases four of the many important places that comprise Springfield's WWII heritage:

“Springfield Armory Museum–Springfield Massachusetts.” September 5, 2015. Wikicommons.

1. Springfield Armory

The main building of the Springfield Armory was built in 1847. The site, however, was declared the first national Armory –a place to manufacture weapons– by George Washington in 1794. Prior to that, it was one of the new country's arsenals–a place to store weapons. Residents in Springfield built guns and munitions for US conflicts, including World War II, over the course of 150 years. The site's production was shut down in 1968 when private companies made most of the military’s weapons.

During World War II, when many other types of manufacturing turned towards war production, the Armory was already set up to increase its output of firearms. Workers at the Armory produced small rifles for individual soldiers to carry--most famously, the M1 Garand Rifle. Invented in 1932 by Canadian-American John Garand, the M1 Garand was a light semi-automatic rifle for soldiers to carry on the battlefield. General George Patton described it as “the greatest battle implement ever devised” [1]. Factory workers made the M1 in Building 104, a state-of-the-art manufacturing facility started in October 1940 and completed in February 1941. The new facilities allowed workers to produce between 1000 and 1,100 M1 Rifles in an 8-hour day, compared with 200 in an 8-hour day before they built the new facility. The Springfield Armory supplied over 3.7 million rifles to the US military over the course of World War II.

The Armory was one of the largest employers in Springfield. Over 13,500 people worked there during the war. Nearly half were women. The facility hired many women under the “Woman Ordnance Worker” program, including Black women. The overall Black population of Springfield grew rapidly during the war, as African Americans came from the South seeking economic opportunity. African Americans made up 8% of the Armory’s workforce. While the jobs were legally desegregated, several Black workers filed complaints of discrimination and harassment. Tensions were also high in 1944 as unionized workers with the American Federation of Government Employees went on an illegal strike protesting wage cuts. Their grievances were never addressed because World War II ended shortly after the strike began. Despite their hard work during the war, over 4,500 Armory workers were laid off after V-E Day in May of 1945.

National Park Service, Springfield Armory NHS, Neg 4729-SA.

As the armory closed, some workers reflected on their friendships. Marion Wimberly, a Black worker, composed a poem for her friend Nellie Doty, who was white.

“The experience I’ve gained can ne’re be lost

The cross I’ve had to bear was worth the cost

You too, I know forgot, amid the fight

That we were different hues: I black, you white…”

Marion Wimberly to Nellie Doty, 1945. Quoted in Wilson, “Crossing Gender and Color Lines at the Springfield Armory.”

The last manufacturing building was closed in 1968, but the Armory continued to house a local television studio until 1980. Despite the closure, Springfield and its environs are still known as “Gun Valley” for the number of weapons invented and manufactured there. The Armory was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960 and became part of the National Park System in 1974 as the Springfield Armory National Historic Site. The Main Arsenal building is now a museum and can be visited today.

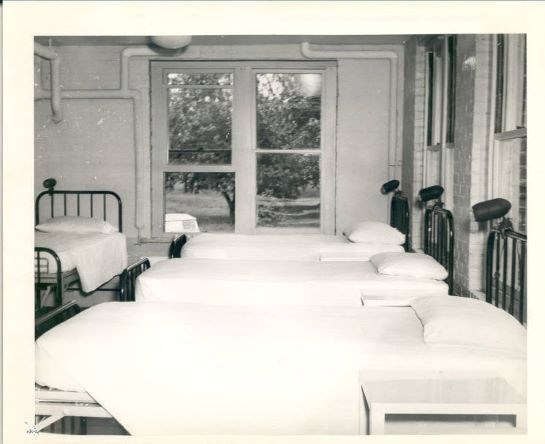

“Infirmary Ward at the US Naval Special Hospital at Springfield College.” Springfield College 1944-45. Armed Forces Collection. Courtesy of Springfield College, Archives and Special Collections.

2. Baystate Medical Center (formerly Springfield Hospital)

Springfield City Hospital was founded in 1870. It moved into its current location on Chestnut Street in 1889. Trustee Lucinda Howard convinced the rest of the Hospital’s Board to add a training school for nurses in 1892. It was among the first nursing schools to be formally accredited by the American Medical Association in 1914. The facility merged to form the Baystate Medical Center in 1974,

Springfield City Hospital became a training site for the United States Cadet Nurse Corps (CNC) during World War II. Congress created the CNC in 1943 to address the nursing shortage at home and abroad. The CNC oversaw 1,125 nursing schools across the U.S. Participating programs were open to all women between the ages of 17 and 35, regardless of race. During their training, women would complete a slightly abbreviated nursing program, with required clinical experiences in surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics, and other medical areas.

“Cadet Nurse Ad- LIFE” January 24, 1944. Life Magazine Vol 16, No 4, pg 31. Wikicommons

The Cadet Nurse Corps took advantage of existing nursing schools, federal resources, and patriotic fervor to recruit and retain nurses. Participants received housing and a modest stipend from the government, in addition to free education, the first for women in the nation. Crucially, 73% of cadet nurses practiced in local hospitals, rather than military posts. On its first anniversary, the Holyoke Telegram described it as “the youngest of the women-in-uniform organizations,” but “also the largest.” By the end of the war, the CNC would help provide training for 15,000 nurses. The Telegram and other newspapers attributed this popularity to “the inestimable value [of the skills] to them as homemakers later on.” But the CNC also trained many women to work outside the home in a career available to women beyond wartime.

When the war ended, the program continued because, as one participant noted, the U.S. still needed nurses. Cadet Nurse Kiyo Sato remembers her motivation to get out of the Japanese incarceration camps but continued the program because "You're making things better and that’s probably what it is, it's something that’s helpful for the community.”

World War II also saw the expansion of employer-provided health insurance, particularly important in a manufacturing center like Springfield. The income generated by fully insured patients accelerated the growth of the hospital after the war, allowing it to offer more services after a period of rationing and personnel shortages.

Though the CNC would continue after the war to meet the challenges of the Baby Boom and other post war medical needs. The program ended in 1948. Springfield City Hospital and nearby Mercy Hospital, which also participated in the CNC, continue offering Nurse Training Programs through the 20th century. Baystate Medical Center sits on the same site and continues to serve as nurse residency program.

3. Springfield Housing Project: Lucy Mallory Village

Springfield is known as the "City of Homes" for its neighborhoods filled with rich Victorian architecture. But Springfield has also worked to provide housing to all residents across the economic range, with varying degrees of success. During World War II, workers and their families moved to Springfield to work at the Springfield Armory and other manufacturing plants. In 1940, Smith & Wesson relocated its headquarters to East Springfield, joining Westinghouse, the Indian Motorcycle Factory, and other companies increasing production for the war effort. To meet the new demand, the federal government helped fund a housing complex under the newly created United States Housing Authority (USHA).

Well-respected New England architect Royal Barry Wills designed the Springfield project. Wills was well known for popularizing and perfecting the Cape Cod Revival Style and writing extensively on historical architecture. Usually, the houses he and his firm designed were single-family homes, drawing on New England nostalgia. Unlike any of his previous work, he designed the units in Springfield for two or four families. Wills drew on familiar colonial styles and early nineteenth-century mill buildings to invoke the industrial work of the city. Springfield built three hundred units before the end of the war in 1945.

The project was named after Lucy Walker Mallory, or “Mother Mallory,” a local missionary and philanthropist who worked with immigrant families in Springfield. After the war and Westinghouse's move to Ohio, the city repurposed Lucy Mallory Village as affordable housing. It was Springfield’s first affordable housing community. Having undergone “urban renewal” renovation in the early 1990s, Lucy Mallory Village is no longer a Federal or State subsidized housing project.

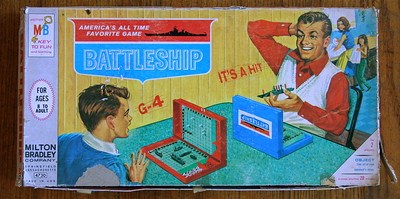

“357/365-‘G-4!’ ‘It’s a Hit!’” November 20, 2009. | Milton Bradley "Battleship"… | Flickr

4. Milton-Bradley Company Factory

The Milton Bradley Company was founded by the eponymous inventor in 1860 in Springfield. Originally, the company produced color lithographs for local businesses and their advertisements. Bradley used his printing machines to make “The Checkered Game of Life,” meant to teach game-players Christian morals and warn of the dangers of vice. As the company grew, Bradley became involved in the Kindergarten Movement. After Bradley died in 1911, the company continued to produce games and educational materials but faltered without its founder and fell into debt during the Great Depression.

In 1940, the Milton Bradley Board appointed Springfield businessman James J. Shea to turn the company around. Among other improvements, Shea renovated the Milton Bradley plant just in time to pivot for World War II production. To help the war effort, Milton Bradley manufactured a universal joint for Army fighter planes and wooden gun stocks.

But Milton Bradley also continued to produce games during the war. Although the company cut the number of games it produced, particularly those that needed metal pieces or other rationed materials, Milton Bradley had several commercial successes during the war. Among the most popular was the updated Milton Bradley Game Kit for Soldiers, which sold $2 million worth of kits over the war (International Directory). The company also introduced the Game of States and Chutes and Ladders. Many of these games tried to inspire patriotism and support for the war.

“Courtyard, Milton Bradley Company Building, Springfield MA” John Phelan September 4, 2013. Wikicommons

The Milton Bradley Factory, which had come to occupy an entire city block, moved to suburban East Longmeadow, Massachusetts in the 1960s. Hasbro bought Milton Bradley in 1984. The Springfield site has been converted to housing and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.

____

This article was written by Alison Russell, a consulting historian with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History’s cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

____

“Dorothy Pryor-1941-1945: Working at the Springfield Armory During World War II.” Deerfield, MA: American Centuries. 2014.

“Forging Arms for the Nation: Springfield Armory” National Park Service. February 4, 2023.

Gebhard, David. “Royal Barry Wills and the American Colonial Revival.” Winterthur Portfolio 27, no. 1 (1992): 45–74.

International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 21. St. James Press, 1998. Printed

Kalisch, Beatrice J., and Philip A. Kalisch. “Nurses in American History: The Cadet Nurse Corps -- in World War II.” The American Journal of Nursing 76, no. 2 (1976): 240–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/3423810.

“Milton Bradley and Life’s Checkered Past.” New England Historical Society.

Snyder, Pam. “The History of Baystate Medical Center.” Baystate Health. January 14, 2019.

“The Springfield Armory: Forge of Innovation.” University of Massachusetts, Amherst and the National Park Service. Accessed June 22, 2023.

Whitehill, Bruce “A Brief History of American Games.” 2002. Excerpt from “Toy Shop” 1997.

Willever, Heather and John Parascandola. “The Cadet Nurse Corps, 1943-48.” Public Health Reports (1974-) 109, no. 3 (1994): 455–57.

Wilson, Rob. “Crossing Gender and Color Lines at Springfield Armory: Women and African Americans Changing the WWII Industrial Workplace.” Past@Present. University of Massachusetts, Amherst. March 24, 2016.

Wilkinson, Jeff. “Who They Were: Royal Barry Wills” Old House Journal 20, No4. July, 1992. 28

Tags

- world war ii

- world war 2

- wwii

- ww2

- springfield armory national historic site

- springfield armory

- springfield

- medical history

- wwii homefront

- wwii home front

- american world war ii heritage city program

- american world war ii heritage city

- awwiihc

- toy

- urban america

- urban history

- women's history

- places of article