Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Abby Kelley Foster .

Article

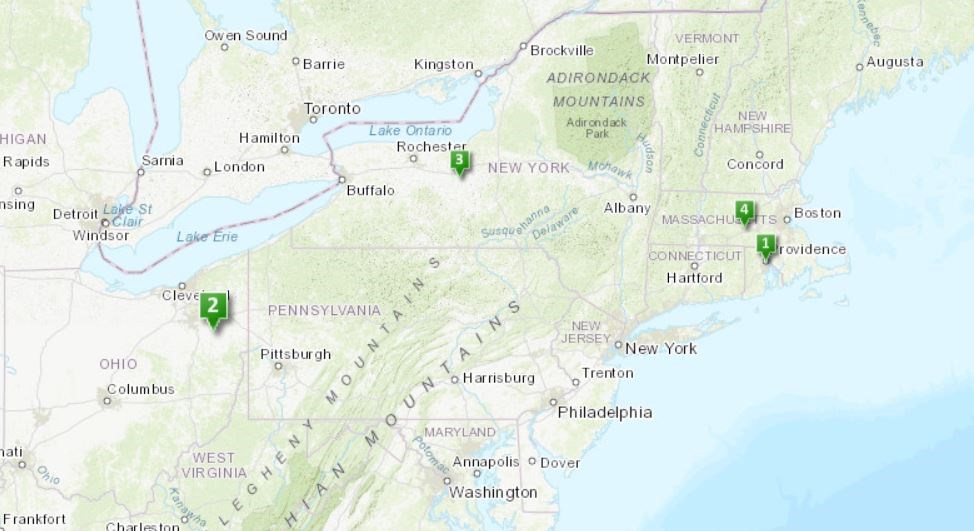

Places of Abby Kelley Foster

“Abby Kelley earned for us all the right of free speech. The movement for equal rights of women began directly and emphatically with her.” -Lucy Stone ¹

Born in 1811 in Pelham, Massachusetts, Abby Kelley Foster was an educator and lecturer. She dedicated her life to abolitionism (a collective effort to end slavery). She also advocated for the equal treatment of women and influenced suffragists like Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone with her ideas on women’s voting rights.

Kelley’s life was defined by her Quaker education and upbringing. She received the best education a woman could in 19th century New England. Her parents taught her that all people should be treated equally.

This article explores some of the places associated with Kelley’s life, from her childhood education at an experimental Quaker school to her adulthood home where she helped freedom seekers on their journey out of slavery.

1. New England Friends Boarding School/Moses Brown School (Providence, Rhode Island)

As a girl, Kelley was educated in a one-room schoolhouse in Worcester, Massachusetts.th century, girls typically only attended elementary school (if that). Receiving all the knowledge she could from the local school, Kelley had the option to begin work at the mills or become a teacher. Wanting to become an educator, Kelley needed more advanced training. As the local high school was only open to boys, Kelley attended the New England Friends Boarding School in Providence, Rhode Island. This school is now known as the Moses Brown School and is listed ion the National Register of Historic Places.

Opened in 1819, the boarding school was housed in a red brick building on a hill overlooking the city of Providence. It’s founder, Quaker abolitionist Moses Brown, tried for years to establish an educational facility in Rhode Island. He felt that the state lacked adequate schools, and he decided to found his own. Both girls and boys were invited to attend, but all facilities were segregated by gender. The school had separate playgrounds, lunch halls, classrooms, and dormitories.

In 1826, Kelley made the approximately forty-mile carriage ride to the New England Friends Boarding School. The building was plain with no decorations, paint, wallpaper, carpets, pictures, or any luxuries. Kelley was instructed to pack only essential items and wear simple clothing. She and the other students awoke before sunrise and began their studies. They spent the end of their day in evening study. Twice a week water was boiled in basins for bathing.²

Although separated into different classrooms, both the boys and the girls received similar instruction. Quakers valued educated women and provided rigorous coursework. Kelley studied spelling, grammar, algebra, botany, astronomy, and accounting,

After her first year at the school, Kelley had to take a leave of absence. She could not afford the tuition. She spent the next several years teaching to earn enough money. She returned to the school for a final year in 1829.

2. Haines House (Alliance, Ohio)

In addition to her captivating speeches, Abby Kelley was known for her ability to organize and mobilize networks of abolitionists. She worked with like-minded thinkers in New England and the Midwest to establish newspapers, found anti-slavery societies, and host informative lectures and conferences. In the 1840s and 1850s, Kelley visited Ohio frequently as she wanted to strengthen anti-slavery sentiments in the state. At the time, Ohio still observed Black Laws which were enacted by the state’s constitution. These laws made it difficult for free Black Americans to participate in society. For example, they could not vote, testify in court against whites, or serve in the state militia. These laws also made it difficult for Black Americans to settle in the state. Black Laws also discouraged those fleeing slavery from staying in the region. Abolitionists like Kelley hoped to repeal Ohio’s Black Laws.

Kelley developed friendships with a number of anti-slavery advocates in Ohio, including the Haines family. Sarah and Ridgeway Haines lived in a federal-style house built by Sarah’s parents, John and Nancy Grant. Construction of the house began in the 1820s and continued into the 1840s. The Grants passed the property on to their daughter and son-in-law who were Quaker abolitionists. The Haines used their home to hide freedom seekers escaping via the Underground Railroad.

Daniel Howell Hise, an abolitionist from Salem, Ohio, recorded Abbey Kelley’s presence at the house. In 1857, he documented in his journal that Kelley and her husband, Stephen Symonds Foster, stayed with the Haines. They were accompanied by several other abolitionists who were lecturing throughout Ohio.³

3. Women’s Rights National Historical Park (Seneca Falls, New York)

Abby Kelley traveled throughout New England and the Midwest lecturing about the horrors of slavery. One of her stops was Seneca Falls, New York. On her trip in 1843, she planned to lecture to the town, which she considered a “stronghold for the cause.”𝟺 The leaders of the churches in town disapproved of her speeches. They believed it was not socially acceptable for a woman to give public speeches – especially in front of men. Unable to find a venue, Kelley spoke at Ansel Bascom's orchard on Ovid and Bayard Streets.𝟻 The property is located between what is today the Women’s Rights National Historical Park and the Elizabeth Cady Stanton House.

In her speech, Kelley talked about how slavery was a sin. She argued that a true Christian would be against slavery. Christianity, according to Kelley, was about treating all people as equals, including women and African Americans. She held six other meetings in Seneca Falls during her stay. Her ideas had a big impact on the community, including several women.

Five years after Kelley’s visit, the women of Seneca Falls (including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Mary Ann M'Clintock) hosted the first women’s rights convention. Historians consider this event, known as the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, the start of the women’s rights movement in the US.

4. Liberty Farm (Worcester, MA)

In 1845, Kelley married fellow abolitionist Stephen Symonds Foster. Several years later, the couple jointly purchased Liberty Farm in Massachusetts. Around the time they bought the property, Kelley gave birth to their only child, Alla. Even as parents, the couple continued to travel and give speeches. They hoped to convince other Americans about the evils of slavery.

When they were not traveling, the Kelley Foster family was aiding freedom seekers traveling the Underground Railroad. They used their home to hide those fleeing bondage. Liberty Farm also served as a meeting place where Kelley Foster hosted other abolitionists.

Abby Kelley Foster was often ill in her later years and did not travel or lecture. She did, however, continue to advocate for women’s rights. As Kelley did not have the legal right to vote on how her tax money was spent, she refused to pay property taxes from 1874 to 1879 as a form of protest. As a result, her house and cows were seized by the state and auctioned off several times. To show their support, Kelley’s friends purchased Liberty Farm and gifted it back to her.

Abby Kelley Foster lived at Liberty Farm until her death in 1887. The property was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1974.

1. Dorothy Sterling, Ahead of Her Time: Abby Kelley and the Politics of Antislavery, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991), 3.

2. Ibid, 18-25.

3. “Haines House,” The Alliance Area Preservation Society, http://www.haineshouse.org/haines-house.html

4. Sterling, Ahead of Her Time, 182.

5. Judith Wellman, “How Abby Kelley Turned Seneca Falls on Its Ear Five Years Before the Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention,” Worcester Women’s History Project, (May 29, 2004), http://www.wwhp.org/Resources/akfoster.html

Bibliography:

Sterling, Dorothy. Ahead of Her Time: Abby Kelley and the Politics of Antislavery. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991.

Wellman, Judith. “How Abby Kelley Turned Seneca Falls on Its Ear Five Years Before the Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention” Worcester Women’s History Project, (May 29, 2004), http://www.wwhp.org/Resources/akfoster.html

http://www.haineshouse.org/haines-house.html

“Abby Kelley Foster,” National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum,

https://www.nationalabolitionhalloffameandmuseum.org/abby-kelley-foster.html

“Abby Kelley Foster: Anti-Slavery, Women’s Rights, and Seneca Falls,” Women’s Rights National Historical Park, accessed June 05, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/upload/abby-kelley-foster-siteb_bl.pdf

“Black Laws,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, accessed June 03, 2021, https://case.edu/ech/articles/b/black-laws

“Black Laws of 1807,” Ohio History Central, accessed June 03, 2021, http://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Black_Laws_of_1807

“Education,” Exhibit Panel, Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park, National Park Service,

“Haines House,” The Alliance Area Preservation Society, http://www.haineshouse.org/haines-house.html

Haines House National Register of Historic Places Nomination, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/71991432

Liberty Farm National Register of Historic Places Nomination, https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/74002046

“Who was Abby Kelley Foster?” Worcester Women’s History Project, http://www.wwhp.org/activities-exhibits/yours-humanity-abby/who-was-abby-kelley-foster

Tags

- women’s history

- women’s rights

- women’s suffrage

- abolitionists

- abolitionist

- abolitionism

- massachusetts

- massachusetts history

- ohio

- ohio history

- new york

- new york history

- rhode island

- rhode island history

- underground railroad

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- national historic landmark

- places of article

- places of...

Last updated: July 30, 2021