Last updated: June 25, 2025

Article

What's Bugging our Forests 2024: Effects of Pests and Pathogens in NCR

By Emma Brentjens, NCRN I&M Science Communications Intern

USDA

Stressed by Pests

National Capital Region (NCR) national parks are part of the Eastern Deciduous Forest, one of the most biologically rich and ecologically important forest biomes in North America. Stretching from southern Canada through the Eastern United States, this forest type supports an extraordinary diversity of native plants, animals, and fungi. However, the health of Eastern Deciduous Forests is increasingly threatened by invasive species, non-native pests, and emerging pathogens.In the NCR, these threats come from both long-established pests and newly introduced organisms. While most forest pests come and go like the common cold, causing only minor and temporary damage, a small number can lead to severe and lasting ecological impacts. Managing these threats is essential to conserving the biodiversity and ecological integrity of these iconic forests.

Here we present the latest data on damage to and death of trees from various pests and pathogens documented by long-term forest vegetation monitoring (2006-2024) by the NCR Inventory & Monitoring Network (NCRN I&M). This includes the lingering effects of emerald ash borer and the expanding potential damage of beech leaf disease. Other forest pests and pathogens observed during forest monitoring are described.

Emerald Ash Borer: “Peak Dead Ash” Passed?

Emerald Ash Borer (EAB, Agrilus planipennis) is a beetle that was first detected in NCR parks in 2014. Since then, it has killed most of the region’s ash trees (Fraxinus spp.). Parks with historically high numbers of ash trees that have suffered major losses include:- Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park (CHOH)

- National Capital Parks- East (NACE), along the Anacostia River

- George Washington Memorial Parkway (GWMP)

- Manassas National Battlefield Park (MANA)

NPS

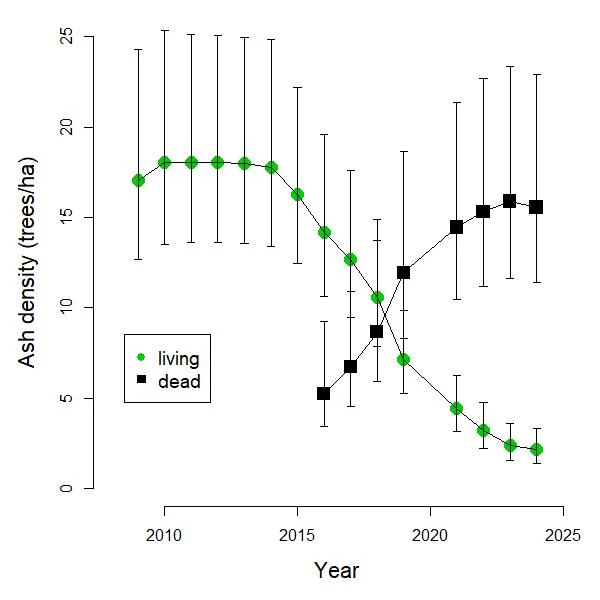

Line graph showing the density per hectare of live ash trees, shown as green circles, and dead ash trees, shown as black squares. Year from 2010 to 2025 is on the x-axis, while trees per hectare is on the y-axis ranging from 0 to 25.

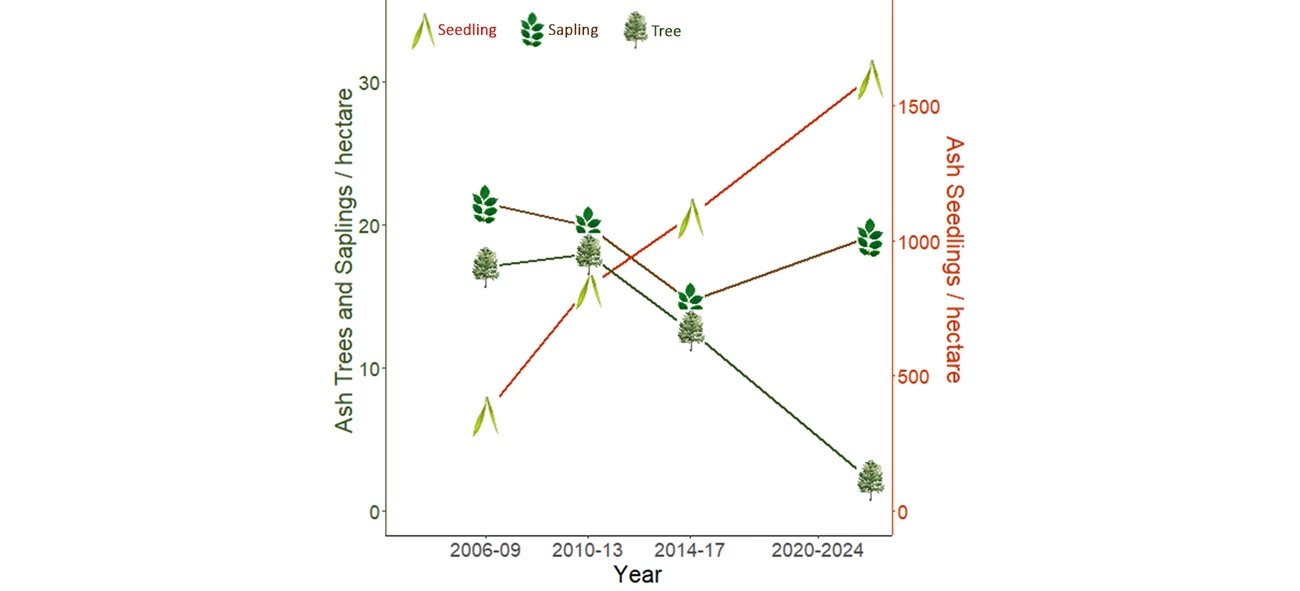

Across the NCR, while the density of living ash trees appears to have stabilized at a low level, the number of ash seedlings and saplings is increasing (Figure 2). Ash seedlings at Catoctin Mountain Park (CATO) make up approximately half of all seedlings recorded. Likewise, ash saplings commonly resprout from the stumps of green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) and pumpkin ash (Fraxinus profunda) in wetland areas at other parks. However, these seedlings and stump resprouts will likely succumb to EAB once they grow large enough to provide good habitat for the beetles.

Line graph showing ash tree, sapling, and seedling density per hectare over time. The monitoring cycles are listed on the x-axis are as follows: 2006–2009, 2010–2013, 2014–2017, 2020–2024. On the left y-axis, trees and saplings per hectare are plotted on a scale of 0 to 30. On the right y-axis, seedlings per hectare is plotted on a scale of 0 to 1500. Tree density points are represented by tree icons, saplings are represented by leaf icons, and seedlings are represented by seed icons.

Beech Leaf Disease Spreading

NPS

- GWMP

- CHOH, particularly in the Potomac Gorge

- Monocacy National Battlefield (MONO)

- NACE, especially in Greenbelt and Piscataway Parks

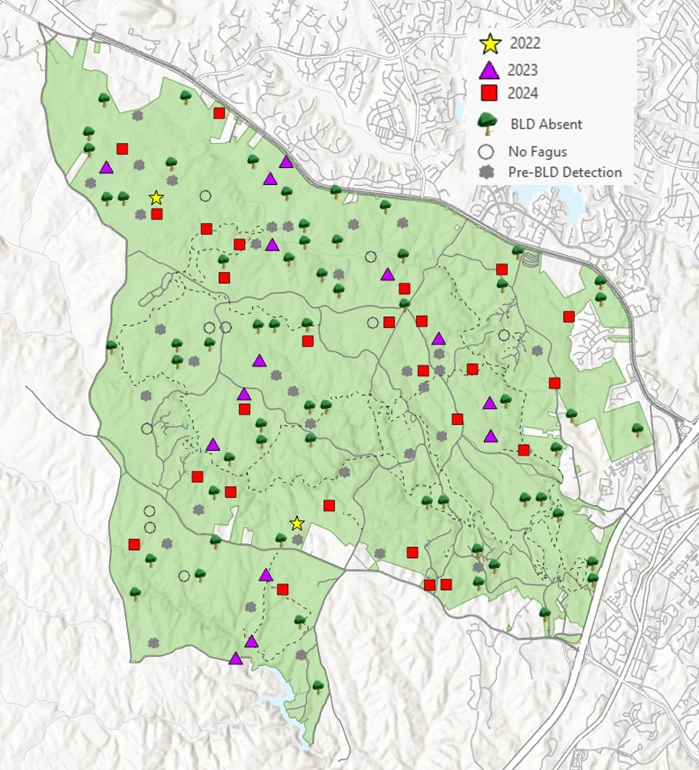

At PRWI’s 145 forest plots, most (133) have American beech trees present. Since initial detection, BLD has been observed in 42 of these plots, 26 of which were confirmed in 2024 (Figure 3).

Topographic map of Prince William Forest Park with the extent of the park shaded green. Each point represents a forest monitoring site. There are 145 sites total. BLD was detected at two sites in 2022 (represented by yellow stars), 14 sites in 2023 (represented by purple triangles), and 26 sites in 2024 (represented by red squares). Tree icons represent plots where BLD is absent (to date), clouds show plots not yet monitored for BLD, and open circles indicate plots with no beech trees.

NPS / Megan Nortrup

Spotted Lanternfly

Spotted lanternfly (SLF, Lycorma delicatula) was first found in the NCR in 2021. Current research suggests that SLF do not typically kill healthy trees but may contribute to decline in trees already stressed by other factors. While the NCRN I&M forest monitoring crew records SLF presence in parks, their overall impact on tree mortality is difficult to assess. These insects are highly mobile, and their presence on a tree does not necessarily indicate active feeding. In the NCR, they are most often observed clustering on tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) and native grapevines.Hemlock Woolly Adelgid and Elongate Hemlock Scale

Despite the effects of hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA, Adelges tsugae) and elongate hemlock scale (Fiorinia externa), eastern hemlock trees (Tsuga canadensis) remain an important species in the region. Hemlocks grow near streambeds and help maintain cool water temperatures by shading the water in winter and spring when many other tree species have no leaves. While Eastern hemlock was never common in the NCR—this is the eastern edge of their range—it has become increasingly scarce as a result of attacks from two non-native insect pests.While many of the hemlock trees once in NCR parks have already succumbed to these pests, surviving hemlock patches were identified at six parks in 2015: CATO, CHOH, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park (HAFE), MANA, MONO, and PRWI. In many cases, active management, such as insecticides and biological controls, have helped maintain those surviving hemlock stands.

Spongy Moth

Spongy moth (Lymantria dispar dispar) larvae feed on deciduous trees, particularly oaks, leaving them vulnerable to other stressors. The last major outbreak in the NCR occurred in 2007-09.Oak Decline

Oak decline is caused by multiple factors (climate change, invasive species, physical damage, etc.) that interact to cause death in oak trees. Oak decline is a major challenge and is the subject of ongoing analysis of oak data by NCRN collaborators at Virginia Tech.Watchlist Pests

In addition to the pests listed above, forest monitoring crews record signs of existing pests chestnut blight and dogwood anthracnose, and keep an eye out for potential emerging pests including:- Elm zigzag sawfly (Aproceros leucopoda): First detected in Virginia in 2021, this non-native insect feeds on elm leaves in a distinctive zigzag pattern, weakening the tree over time.

- Beech bark disease: This complex disease results from the combined effects of an invasive scale insect (Cryptococcus fagisuga) and two fungal pathogens (Neonectria faginata and Neonectria ditissima). It causes cankers, bark damage, and eventual tree death.

- Oak wilt: Caused by a fungus (Bretziella fagacearum) that is transmitted by an insect. The fungus causes wilting leaves by infecting a tree’s vascular system.

- Southern pine beetle (Dendroctonus frontalis): These tiny beetles attack pine trees by tunnelling under the bark to lay their eggs.

Parks Taking Action

With the support of regional experts and federal partners, national parks in the NCR are actively working to mitigate the threat of forest pests and pathogens. These efforts reflect a coordinated, science-based approach to protecting forest health across the region.To address hemlock woolly adelgid, CATO has conducted targeted and preventative insecticide treatments on vulnerable hemlock trees. With assistance from regional specialists, the park is also planning to release Laricobius nigrinus and Laricobius osakensis beetles as biological control agents, or organisms used to suppress invasive pests. These predatory beetles—native to the Pacific Northwest and Japan, respectively—feed exclusively on adelgids and have shown success in keeping HWA populations at levels that minimize damage to trees. Likewise, MANA is working with the U.S. Forest Service’s Forest Health Protection team and NCR regional experts to conduct a detailed biological evaluation of their hemlock trees to help guide future management decisions.

To address the threat of emerald ash borer, the Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has extensively studied and approved the use of four species of parasitoid wasp as biological control agents. These include three species that eat EAB larvae—Tetrastichus planipennisi, Spathius galinae, and Spathius agrili—and one that eats EAB eggs, Oobius agrili. The larval wasps lay their eggs inside EAB larvae tunneling beneath the bark, while Oobius agrili parasitizes EAB eggs laid on tree surfaces. Research has shown that these wasps can significantly reduce EAB populations over time. APHIS has released wasps in 34 states and DC with the goal of establishing self-sustaining populations in their release sites. Recoveries of wasp larvae in several states including DC indicate that the populations are successfully reproducing in the wild. However, the long-term effects of these biocontrol agents on ash tree regeneration in NCR parks are not yet known.

Everyone Can Help

Anyone can play a role in reducing the spread of forest pests and pathogens. Here are some steps you can take to protect our parks:- Don’t transport firewood. Buy wood 10 miles or less from where you burn it.

- Stay on marked trails and always keep your dog on leash.

- Clean off your shoes after visiting a park or between visits to different parks.

- Report any pest sightings to your local county authorities or department of agriculture and report them on iNaturalist.

- To learn more about caring for trees, check out resources from the International Society of Arboriculture.

Further Reading

- Borowy, Dorothy. 2020. Oak Decline.

- Borowy, Dorothy. 2021. Biocontrols in NCA.

- Duan, J.J., Van Driesche, R.G., Schmude, J., Crandall, R., Rutlege, C., Quinn, N., Slager, B.H., Gould, J.R. and Elkinton, J.S., 2022. Significant suppression of invasive emerald ash borer by introduced parasitoids: potential for North American ash recovery. Journal of Pest Science, 95(3), pp.1081-1090.

- Harkness, Hannah. 2024. Beech Leaf Disease: Mistaken Identity.

- Harkness, Hannah. 2024. When Forests Come Down with a Bug: Forest Pests in the Greater DC Area.

- Tait, Nicholas. 2023. Ash Tree Update 2022.

Tags

- anacostia park

- antietam national battlefield

- baltimore-washington parkway

- catoctin mountain park

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- fort dupont park

- fort foote park

- fort washington park

- george washington memorial parkway

- glen echo park

- great falls park

- greenbelt park

- harpers ferry national historical park

- kenilworth park & aquatic gardens

- manassas national battlefield park

- monocacy national battlefield

- national capital parks-east

- oxon cove park & oxon hill farm

- piscataway park

- prince william forest park

- rock creek park

- theodore roosevelt island

- wolf trap national park for the performing arts

- anacostia park

- antietam national battlefield

- baltimore-washington parkway

- catoctin mountain park

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- fort dupont park

- fort foote park

- fort washington park

- george washington memorial parkway

- glen echo park

- great falls park

- greenbelt park

- harpers ferry national historical park

- kenilworth park & aquatic gardens

- manassas national battlefield park

- monocacy national battlefield

- national capital parks-east

- oxon cove park & oxon hill farm

- piscataway park

- prince william forest park

- rock creek park

- theodore roosevelt island

- wolf trap national park for the performing arts

- ncrn

- ncrn im

- forests

- pests

- forest pests

- pathogen

- resilient forest management

- resilient forests

- trees

- emerald ash borer

- beech leaf disease

- spotted lanternfly

- hemlock woolly adelgid

- elongate hemlock scale

- spongy moth

- oak decline

- forest