Last updated: January 20, 2026

Article

Biocontrols in NCR

Tom Potterfield, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The NPS recently approved plans to use an insect (knotweed psyllid, Aphalara itadori) as a biological control against the highly invasive plant Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) at the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park. So, what exactly is biological control and why don’t we hear more about this method of management?

Biocontrol Agents

Biological control (biocontrol) is a pest management strategy that involves introducing a natural enemy (biocontrol agent) to an area to suppress and control a non-native pest. Biological control agents can include predators, parasites, parasitoids (i.e., insects that are parasitic in their larval stage and free-living as adults), and pathogens (bacteria, protists, fungi, and viruses).

A Brief History of Biocontrols

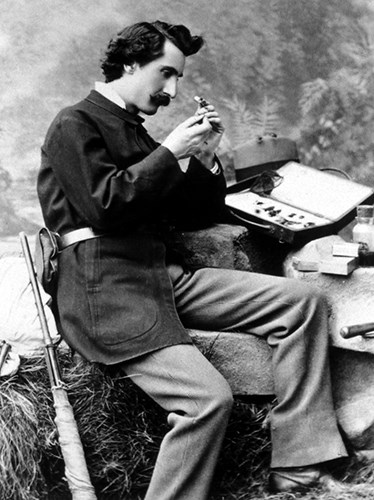

Special Collections, USDA National Agricultural Library. https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/speccoll/items/show/323

The practice of using biocontrols dates back centuries. The first written documentation in 304 AD describes how farmers used ants to protect their citrus trees from pest infestations in China.

The development of modern biological control techniques can be attributed to Charles Valentine Riley, a British-born American entomologist who studied agricultural pests. Riley is known as the “Father of Biological Control.” He studied and released numerous biological control agents, and is responsible for the first example of achieving complete control of a pest with a biocontrol agent.

In the late 1800s, cottony-cushion scale (Icerya purchasi) was a major pest of citrus trees. It was accidentally introduced to California from Australia in a nursery tree shipment. At the time, many citrus growers were so desperate to get rid of it they resorted to using cyanide fumigation and burning their orchards, but without long-term success. In an effort to control the pest, Riley and his colleagues identified two natural enemies of cottony-cushion scale in Australia that had the potential to serve as effective biocontrol agents in the U.S. In 1888, they released a parasitic fly species, Cryptochaetum iceryae, and the Australian Vedalia beetle (Rodolia cardinalis) in San Mateo, CA. Within two years, cottony-cushion scale was completely controlled and no longer posed a threat to citrus production.

Since then, numerous species have been released around the world to control various agricultural and environmental pests. More than 200 non-native invasive insects and 50 plant species have been partially or completely controlled with biocontrol agents (Heimpel & Cock 2018). Although there have been many success stories in the history of biological control, there have also been failures, some of which have caused incalculable ecological and economic damages.

U.S. Geological Survey

Among the most notorious is the cane toad (Rhinella marina). In 1935, 102 cane toads, riding in suitcases, were introduced from Puerto Rico to Australia to control greyback cane beetles (Dermolepida albohirtum), that were destroying sugar cane—a major agricultural export of Australia. Once introduced, the toads quickly outcompeted native species and began feeding on a wide variety of native insects, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals, driving many of Australia’s endemic species to the brink of extinction. The toad’s defense mechanism, toxic venom secreted from glands behind its eyes, also impacted native predators, killing birds, snakes, and even full-grown crocodiles that attempted to eat the toads. Today, the cane toad is considered one of the world’s top 100 invasive species; there are an estimated 200 million cane toads in Australia today and the government has spent more than $20 million on management and research to combat this invasive species.

A.V. Evans

In the U.S., harlequin lady beetles (Harmonia axyridis) were introduced from Asia around the start of the 20th century to control aphids on crops. These beetles are dominant aphid predators and quickly displaced native lady beetles (family Coccinellidae) in agricultural systems. Harlequin lady beetles also carry a microsporidia parasite, which doesn’t harm them but does kill many native lady beetles, of which there are more than 400 species in North America. Experts today are still debating the effect of the harlequin lady beetle on native lady beetles in their native natural habitat.

Modern Biocontrol & USDA Review Process

These early failures stigmatized classical biocontrol. That, combined with the widespread production of inexpensive synthetic pesticides, has resulted in decreased reliance on alternative methods like biocontrols for managing pests. However, when used properly, biological control can be a safe and very effective pest management strategy.

Many lessons have been learned from the long history of biocontrol use. The modern process of evaluating biocontrols is rigorous and incorporates these early lessons.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Plant Protection and Quarantine division (USDA-APHIS-PPQ) is the federal entity responsible for providing testing guidelines and authorizing the importation of biocontrol agents into the U.S. PPQ works with various organizations, including universities, local districts, and federal, tribal, and state agencies, to identify and assess potential biocontrol agents. Evaluating an organism as a potential biocontrol for a plant pest takes an average of 10 to 15 years and costs $1-2 million.

Once a target pest has been identified, USDA follows a series of steps before approving a potential biocontrol agent for the target pest:

-

Reviewing of the scientific literature and consulting with subject-matter experts to identify natural enemies (potential biocontrols) from the target pest’s native range. This step may result in a list of 5 to 10 organisms.

-

Assessing the survival and performance of each natural enemy under different environmental conditions found in the pest’s introduced range; e.g., temperature, degree days, moisture, drought, season, habitat, etc. (Only those organisms that pass move on to the next step.)

-

Collecting the natural enemies in their native range and rearing them in a secure lab to prepare them for additional testing.

-

Testing for host specificity. The natural enemy is raised with the target pest (plant or insect), along with native non-target species, commercial species, and any related threatened and endangered (T&E) species. Tests include all life stages (e.g., egg, larva, adult) of the hosts and natural enemy. Potential biocontrol agents must show high specificity for the target pest; i.e., they must attack or infect the target pest 99.99% of the time. If there are any direct or indirect impacts to T&E species, the natural enemy is immediately eliminated as a candidate.

-

For biocontrol candidates that target plant pests, approval must be given by the APHIS Technical Advisory Group (TAG). TAG is comprised of 15 federal and state agencies who evaluate proposed introductions of weed biocontrol agents in the U.S. and provide an exchange of views, information, and advice to researchers. Only after approval by TAG, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Tribal Councils does USDA-APHIS-PPQ officially approve a candidate weed biocontrol agent for release.

- APHIS-PPQ consults with state departments of agriculture, and completes an Environmental Assessment or Environmental Impact Statement. If the process is successful, APHIS recommends use of the biocontrol by issuing a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI).

- USDA-APHIS-PPQ releases biocontrol permits to states.

Biocontrols in National Parks

In the National Capital Region, biocontrol use has been limited. In addition to the approved the release of knotweed psyllid (Aphalara itadoria) to suppress the invasive Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) at the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park, biological controls have only been used twice in the region. The first was in 1982, when NPS resource staff, Jim Sherald and Dick Hammerschlag, attempted to inoculate American elms (Ulmus americana) on the National Mall against Dutch Elm Disease (Ceratocystis ulmi) with isolates of Pseudomonas syringae—a bacterium known to be antagonistic to the disease in a laboratory setting. Unfortunately, the bacterium did not inhibit the disease, but this was the first time in the NPS that a pathogen was used as a biological control agent. The second was in 2019 when the a predatory mite (Amblyseius andersoni) was released at Rock Creek Park’s Meridian Hill Park to treat boxwood spider mites (Eurytetranychus buxi).

Slow adoption of biocontrols in the region is in part due to the approval process required for biocontrol use (it is simpler to get approval for pesticide use) and the fact that many managers are not as familiar with the use and potential effectiveness of biocontrols as an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategy. The NPS IPM program is currently working to reduce the paperwork burden that parks face when seeking to use federally approved biocontrols and has held public webinars to increase awareness about biocontrols. The goal is that these efforts will help parks adopt a more integrated approach to effectively and safely managing pests in the region. Stay tuned for future articles about biocontrols in this publication.

Learn More

Milan, Joseph. “Fundamentals of Biocontrol and Their Efficacy on Select Species” An NPS Integrated Pest Management webinar touching on target specificity and the safety of biocontrol use. NPS-only Link. External YouTube Link.

Biocontrol of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, Forest Service fact sheet

Biological Control of Emerald Ash Borer, USDA APHIS fact sheet

References

Heimpel, George & Matthew Cock. 2018. Shifting paradigms in the history of classical biological control. BioControl (2018) 63:27–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10526-017-9841-9