Last updated: May 22, 2020

Article

Eastern Hemlocks in the National Capital Region

NPS/Thomas Paradis

Importance

- Eastern hemlocks are evergreen trees native to National Capital Region (NCR) parks.

- They often grow in patches along streamsides and provide cooling shade in winter and spring when other trees have no leaves

- Two non-native insect pests have killed many of the Eastern hemlocks in NCR forests.

- Some trees have survived, but many are being replaced by other tree species that can’t shade streams year-round as hemlocks do.

About Eastern Hemlocks

Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) is a long-lived, evergreen tree native to the eastern United States. In the National Capital Region (NCR), naturally occurring stands of Eastern hemlock are usually restricted to stream bottoms and north facing slopes in cool, steep terrain. In stream-side habitats, hemlocks maintain cool water temperatures by shading the water in winter and spring when many other tree species have no leaves.While Eastern hemlock was never common in the NCR—this is the eastern edge end of their range—it has become increasingly scarce as a result of attacks from two non-native insect pests: hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) and elongate hemlock scale (Fiorinia externa). These pests have had devastating impacts on hemlocks across much of their

range, at a time when warming temperatures have already stressed these cool-climate trees. Yet even where the insects have been established for a decade or more, some trees still

survive.

NPS/Thomas Paradis

Mapping Hemlocks

In 2015, the NCR Inventory & Monitoring Network (NCRN I&M) set out to document the location of remaining Eastern hemlock stands and to assess tree condition at these sites. In addition, we collected data to illustrate which tree species are replacing Eastern hemlocks in the forests where they are most impacted by non-native pests.Based on information from parks, regional vegetation maps, and forest-related reports, NCRN I&M staff and interns from University of Maryland, Baltimore County identified areas where naturally occurring hemlocks were once dominant (so-called “hemlock patches”). Potential hemlock patches were identified at 6 parks: Catoctin Mountain Park, Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, Manassas National Battlefield Park, Monocacy National Battlefield, and Prince William Forest Park. A field team then mapped these patches with global positioning systems.

Hemlock-dominated forest patches at C&O Canal, Manassas, and Monocacy were relatively small. We mapped 3.9 hectares (ha) at C&O Canal, 1.3 ha at Manassas, and 0.6 ha at Monocacy. The patches at Catoctin, Harpers Ferry, and Prince William were larger (47, 8, and 7 ha, respectively). At these parks, we collected vegetation data at randomly located inventory plots to better understand current forest structure and diversity and to predict how these forests may change in the future.

Hemlocks in the Capital Region

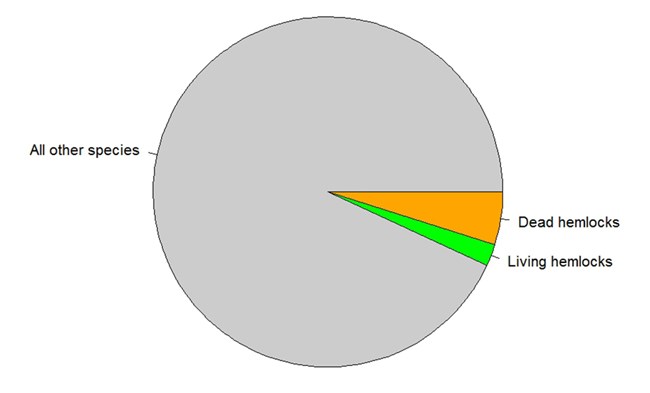

Eastern hemlocks were a significant part of the canopy in hemlock patches where we sampled vegetation plots, accounting for ~8% of the basal area present, including both living and dead trees (Figure 1). Basal area is a measure of the volume of wood in a given area based on tree size, as opposed to the number of trees per area.The plot data were used to determine the condition of hemlocks and to document all tree species of tree, sapling, and seedling size. In the 60 plots sampled, we recorded 112 standing hemlock trees, 34 of which were alive. Among the living hemlock trees, 38% were infected with the adelgid or the scale.

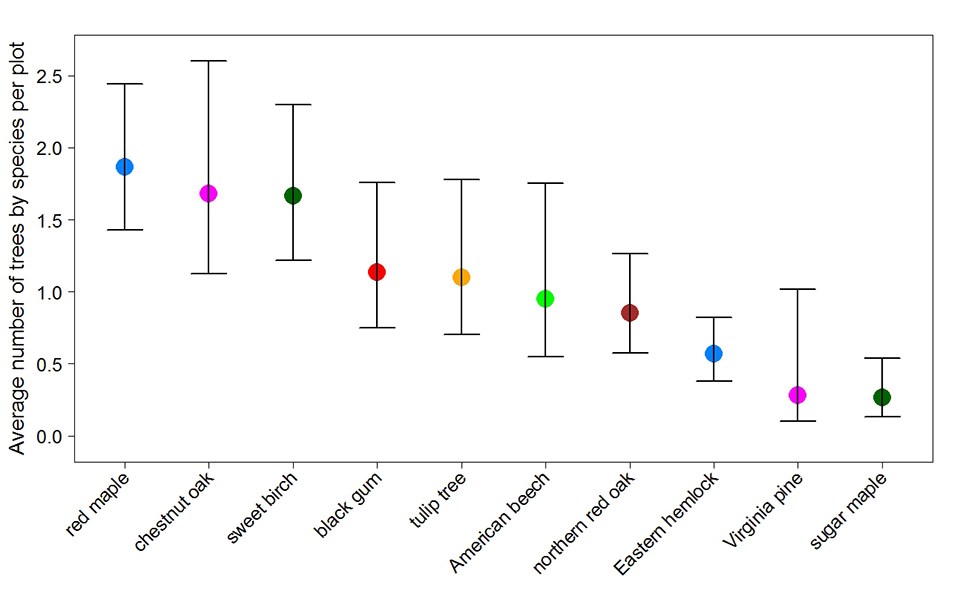

patches, it was only the 8th most common tree species (Figure 2). As hemlocks continue to decline, the other species shown in Figure 2 may take the place of hemlocks in the forest canopy.

However, since few of these species are evergreen, the new canopy will be unable to replace some of the functions of hemlocks in this forest (e.g. the cooling shade hemlocks provided in winter and spring).

Survivors at Prince William Forest Park

Overall, the loss of hemlock trees in the NCR has been profound. Yet, in one small area of Prince William Forest Park, hemlocks remain unscathed. In 2015, prior to any preventative treatments by park staff, hemlocks in that area showed no signs of infection by the adelgid or scale.References

Data from the NCRN Hemlock Inventory Project is available online. A geospatial dataset contains locations of mapped hemlock patches, sampled plots, and individual live and dead trees at Catoctin, C&O Canal, Harpers Ferry, Manassas, Monocacy, and Prince William. In the hemlock patches mapped, data was gathered on infection status of all hemlocks and all tree species present of tree, sapling, and seedling size.Further Reading

Matthews, E. and M. Nortrup, 2017. NCRN Resource Brief: Eastern Hemlocks in Catoctin Mountain Park.Matthews, E. and M. Nortrup, 2017. NCRN Resource Brief: Eastern Hemlocks in Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

Matthews, E. and M. Nortrup, 2017. NCRN Resource Brief: Eastern Hemlocks in Prince William Forest Park.

To learn more about how National Park Service scientists are monitoring the health of parks in the National Capital Region, visit the NCRN I&M website.

Click to access a print-friendly version of this article.

Tags

- catoctin mountain park

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- harpers ferry national historical park

- manassas national battlefield park

- monocacy national battlefield

- prince william forest park

- eastern hemlock

- tsuga canadensis

- forest pests

- invasive pests

- ncrn

- i&m

- hemlock woolly adelgid

- forest