Last updated: December 17, 2025

Article

Vegetation and Soil Trends, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park and Curecanti National Recreation Area

NPS/Amy Washuta

What We Wanted to Know

At a Glance

- Sagebrush shrublands support Gunnison sage-grouse, but native grasses are declining.

- Pinyon-juniper woodlands are stable but face future risks.

- Aspen forests are declining due to high tree mortality.

- Gambel oak shrublands remain resistant to change, though native grasses are decreasing.

Ecosystems are always shifting—some years bring growth, others loss. To better understand these changes at Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park (BLCA) and Curecanti National Recreation Area (CURE), the Northern Colorado Plateau Network (NCPN) has monitored vegetation and soil conditions since 2011.

These landscapes—from sagebrush shrublands to old-growth pinyon-juniper forests—are facing increasing pressures that cause plant communities to shift and expose various conservation challenges. Are native grasses holding their ground? Can forests recover after drought? The answers to these questions can present options for informed management.

What We Did

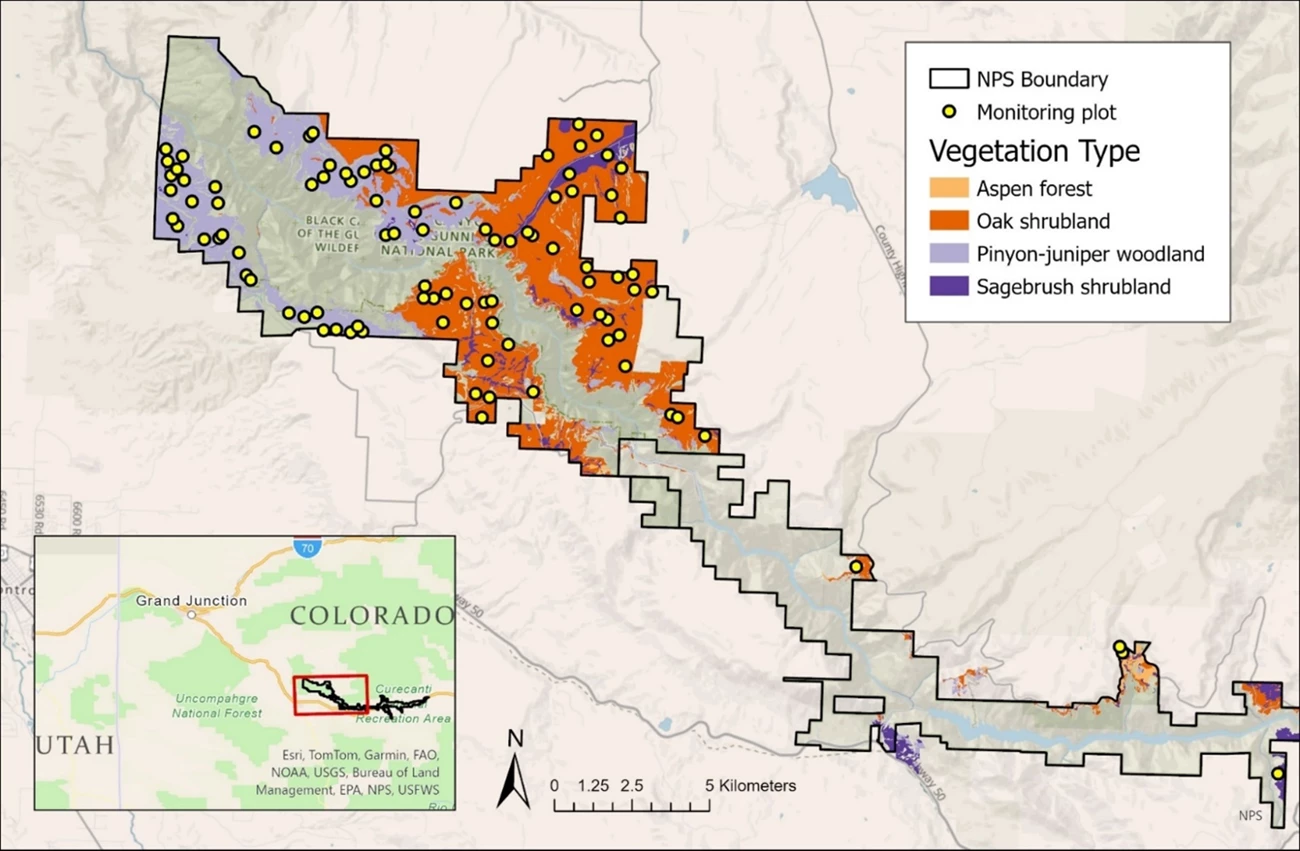

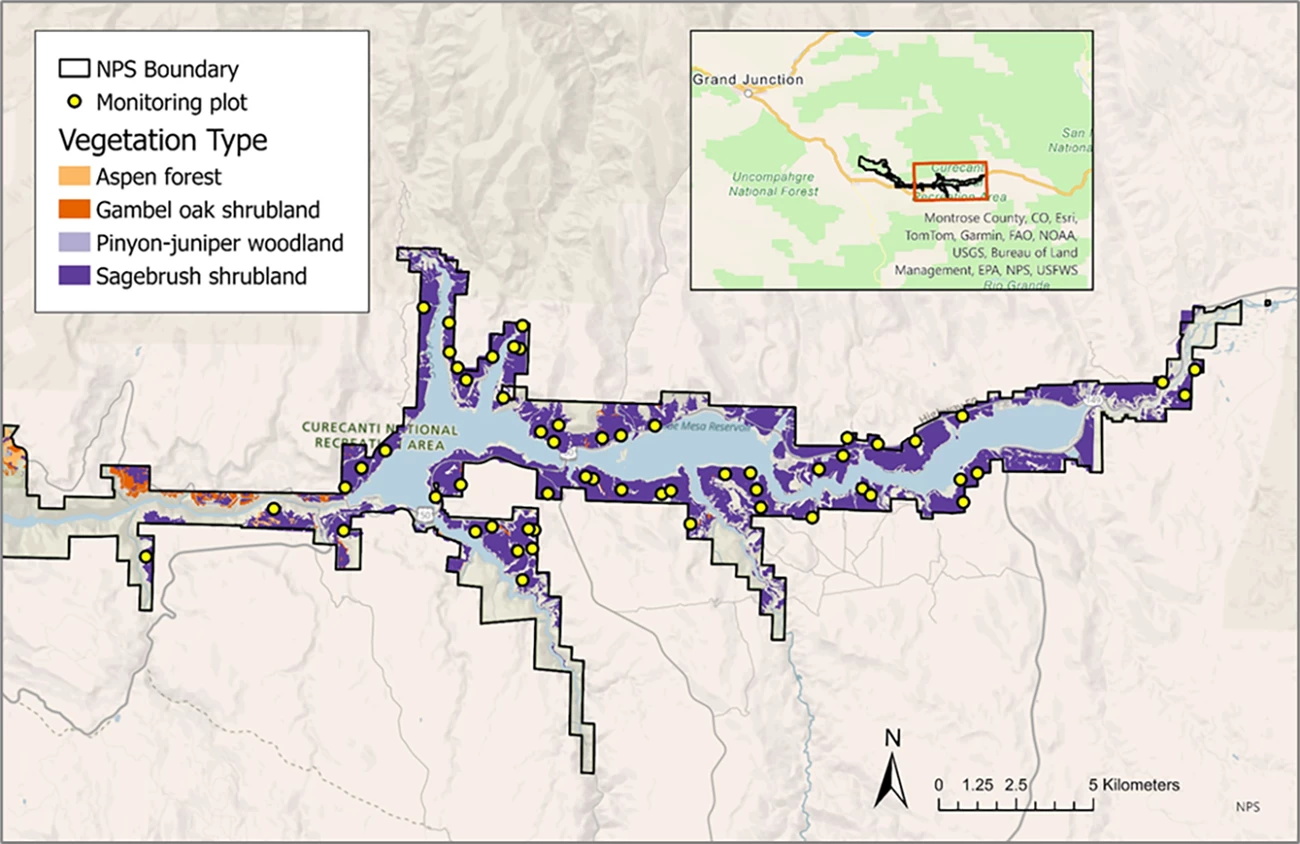

NCPN uses a structured monitoring approach to track ecosystem changes. A pilot study (2008–2010) refined methods, leading to 153 permanent monitoring plots across different elevations and vegetation types. Since 2011, researchers have revisited these sites every five years, surveying up to 45 plots annually to measure plant cover, soil stability, and other key indicators (Figures 1 and 2).

NPS

NPS

Fieldwork occurs in late spring and summer when plants are most active. Crews assess plant cover, tree and shrub density, and soil conditions using standardized methods. These data show how ecosystems respond to grazing, climate shifts, and fire.

What We Learned

Long-term monitoring at BLCA and CURE shows that while some ecosystems remain resistant to change, others are experiencing shifts in plant composition, fire risk, and water availability that may impact habitat and ecosystem health.

Sagebrush Shrublands: A Shifting Landscape

Sagebrush shrublands support wildlife, including the Gunnison sage-grouse, but grazing is shifting plant composition. While overall shrub and total grass cover remained stable, native grasses declined at an annual rate of -0.33%, non-native grasses increased, and forb cover stayed low, affecting habitat quality (Figure 3).

NPS

Pinyon-Juniper Woodlands: Fire Risk and Changing Grass Cover

Pinyon-juniper woodlands remain relatively stable, but native grasses have declined, and invasive species like cheatgrass—while not yet widespread—could increase fire risk by adding dry fuel (Figure 4). Large fires in similar landscapes have turned forests into shrublands, emphasizing the need for ongoing monitoring and fire prevention.

NPS/Amy Washuta

Aspen Forests: Struggling to Survive

Aspen forests at CURE are declining, with fewer mature trees, canopy closure decreasing by 1.6% per year, and seedlings unable to mature due to heavy browsing (Figure 5). While non-native plants like Kentucky bluegrass are widespread, native perennial grasses remain stable, but the forests' long-term survival is uncertain at the lower edge of their climate range.

NPS/Amy Washuta

Gambel Oak Shrublands: Stable but Shifting

Gambel oak shrublands remain stable despite environmental stressors (Figure 6). However, native grasses have declined by 5% since 2011, while forb cover—especially in wetter years—has increased. These shrublands appear resistant but understory components may shift with long-term climate changes.

NPS

Water’s Role in Vegetation Changes

Water availability is a major driver of ecosystem change. Drier conditions were linked to a reduction in native grass cover in most vegetation types at BLCA and CURE. As temperatures rise and precipitation patterns shift, water shortages will likely continue to influence these landscapes.

What We Recommend

Protecting BLCA and CURE’s upland ecosystems requires targeted conservation strategies to manage grazing, fire risk, forest decline, and water scarcity while sustaining habitat quality and resilience.

Sagebrush Shrublands

Sagebrush shrublands remain vital for the Gunnison sage-grouse, but grazing is shifting plant composition. Managers can help support sagebrush by monitoring grazing impacts from livestock and native ungulates, maintaining allotment boundary fences to prevent trespass, and prioritizing the protection of resilient areas with low non-native plant cover.

Pinyon-Juniper Woodlands

Pinyon-juniper woodlands are in good condition, and invasive species remain low. Managers can protect high-value woodlands from fire and continue to monitor and control for cheatgrass, which could increase surface fuels.

Aspen Forests

Aspen forests are struggling as fewer saplings reach maturity due to browsing and changing climate conditions. Managers can identify areas most likely to support aspen in the future while preparing for inevitable shifts in vegetation.

Gambel Oak Shrublands

Gambel oak shrublands continue to thrive, but consistent decline in cool-season native perennial grasses across vegetation types warrants concern. Managers should consider this functional group as vulnerable when making decisions regarding livestock grazing and wildlife management.

Water

Water scarcity is shaping vegetation trends across the region, particularly in the driest months. Park managers can track water deficit trends and incorporate water availability into conservation planning to help mitigate ecosystem stress and prepare for future drought conditions.

Ongoing conservation efforts will give native species a better chance to persist, ensuring BLCA and CURE’s upland ecosystems remain resilient in the face of change.

Information in this article was summarized from Vegetation and Soil Trends, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park and Curecanti National Recreation Area, 2011–2022 by C. Livensperger. Content was edited and formatted for the web by E. Rendleman.