Part of a series of articles titled Of Poetry and Nature: Longfellow's Green Rhyme and Verse.

Previous: Longfellow's Environmental Niche

Next: Nature Poetry Resources

Article

Has art ever changed how you see the world?

In the mid-1800s, more people had the means to access, explore, and sometimes settle in the furthest reaches of the country.1 In their explorations, settlers encountered the land they considered stretches of “frontier”—think the plains of the Midwest—or expanses of “wilderness”—think the glacier-carved valleys of Yosemite (despite being the homeland of the Miwok people). This land became emblems of national pride, and people began to consider it a significant cultural resource.

The picturesque nature of America also became a source of inspiration for paintings, songs, prose, and of course, poetry. Artists created to explore and challenge perspectives about their relationships with the natural world. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow followed this cultural inclination, grounding much of his poetry in nature to help him achieve create a national literary canon. In doing so, Longfellow’s depictions of nature primarily represent a reciprocal relationship between humanity and the natural world.

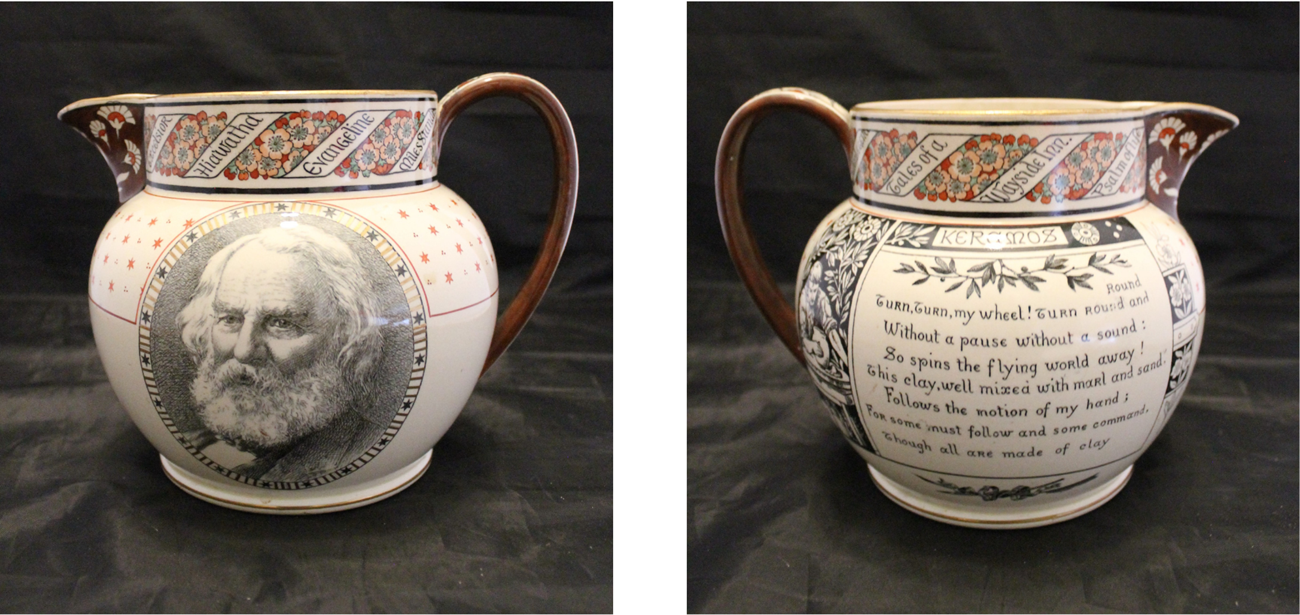

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 4306)

What value did Longfellow see in this relationship between nature and poetry?

Perhaps the most direct answer is not in his poetry, but in one of his few works of prose. In January 1832, Longfellow wrote “The Defence of Poetry,” an essay meditating on Elizabethan poet Philip Sidney’s “Defence of Poesy,” a preeminent work of literary criticism in the 1500s. Published in The North American Review, Longfellow’s article upholds poetry as a vital medium for establishing a national cultural identity. In the essay, Longfellow is cognizant of the dominant European literary tradition in the Western world. Knowing that America’s literary tradition is still in its infancy, he outlines his ideals for American poetry, most importantly the distinction from European aesthetics and culture.

To achieve this distinction, he calls on poets to be authentic, to write “from their own feelings and impressions, from the influence of what they see around them, and not from any preconceived notions of what poetry ought to be, caught by reading many books and imitating many models."2

A vital part of this authenticity, Longfellow continues, is poetry grounded in a poet’s local environment. Of descriptions of natural scenery in American poetry, Longfellow implores: “let us have no more sky-larks and nightingales. For us they only warble in books. A painter might as well introduce an elephant or a rhinoceros into a New England landscape.” Longfellow’s attention to the local fauna speaks to his environmentalist tendencies. For a poem to have integrity, Longfellow seems to be saying, its poet must create from the natural world, integrating local species or formations into their work with accuracy. He implies that a poet must have some local ecological knowledge.

He takes this idea further by instructing poets to “let the description [of scenery] be graphic, as if it had been seen and not imagined.”3 This distinction from “seen” and “imagined” conveys the Longfellow’s core belief that poetry reflects what already exists; the poet is merely recording observations that come from the world around them. Compared to his contemporary and friend Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose “transparent eyeball” metaphor argued that humans must absorb—not reflect—to become one with nature, Longfellow’s philosophy of art and nature is much more anthropocentric. Unlike Emerson, who argues to dissolve the classical hierarchy of human over nature, Longfellow still posits nature as a means for humans to create.

In another one of his narrative poems, Longfellow echoes similar sentiments. Published several decades after “Defence of Poetry,” Longfellow’s 1878 poem “Kéramos” centers on a potter (the title is the Latin word for “ceramics”) working diligently at his wheel. The narrator then takes a sweeping tour of places famous for ceramics, from the Italian town Gubbio to the Japanese villages of Imari, as well as mythological figures, from the Egyptian Ammonn, Osiris, Isis to the Greek Achilles, Aphrodite, Alcides. Periodically, the narrator returns to a refrain first sang by the potter: “Turn, turn, my wheel!” followed by a corresponding lesson on the theme of inevitable mortality and unity with all living things.

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 5829)

Towards the end of the poem, the narrator muses:

Art is the child of Nature; yes,

Her darling child, in whom we trace

The features of the mother's face,

Her aspect and her attitude,

All her majestic loveliness

Chastened and softened and subdued

Into a more attractive grace,

And with a human sense imbued.

Here, the relationship between art and nature differs slightly from the one Longfellow described in “Defence of Poetry.” While good art is a “tracing” of nature, the “human sense” improves the form of nature; humans are capable of creating of creating something better than nature. At the same time, artists create these “chastened and softened and subdued” depictions of nature as a way to give back to motherly Nature. The poem confirms this: “He is the greatest artist, then, / Whether of pencil or of pen, / Who follows Nature.”

Undoubtedly, Longfellow cared about nature and the environment. Despite his rather traditional views of the relationship between human and nature, the earnest care he puts into tending the landscape, whether it was the one he crafted through words or the one in his own backyard, should not go unnoticed.

Close reads of his poetry reveal Longfellow’s earnest belief in cultivating a relationship of mutual exchange and respect between humans and nature.

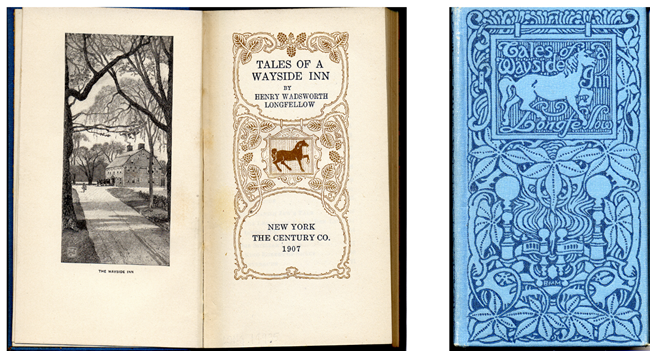

Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Museum, A. Augustus Healy Fund, 50.118

Longfellow understood natural imagery as a key part of the culture and landscape of his 1845 narrative poem Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie.

On January 9th, 1847 Longfellow wrote in his journal: “I want to have an illustrated edition [of ‘Evangeline’] … I shall have margins from Americal [sic] subjects – such as Indian corn, hops, mescaline vines and festoons of evergreens and the mournful pines.”4

These illustrations would only enhance the natural environment Longfellow paints through unrhymed verse; as the titular Evangeline traverses across North America in search of her lover, Gabriel Lajeunesse, the poem gives an accompanying survey of the flora and fauna of the different biomes.

His ardent respect for the environment is clear by the opening stanza:

This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.

Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighboring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest.

Longfellow personifies the forest, casting the trees as subdued beings even as the ocean roars, “wailing” in a sort of lamentation for the following tale of separated love and the exiled people. Longfellow presents a post-human landscape. This landscape is distinct from the dominant eco-narratives of 21st century media; rather than a razed expanse of land left after a human-induced ecological disaster, Longfellow’s post-human nature yearns for its human companions, suggesting that the Acadian people achieved harmony and balance with the land they lived on. With this, Longfellow prompts the reader to examine the elements of the pastoral life presented in the first canto of the poem that follows.

Take this excerpt, for instance:

Dikes, that the hands of the farmers had raised with labor incessant,

Shut out the turbulent tides; but at stated seasons the flood-gates

Opened, and welcomed the sea to wander at will o'er the meadows.

Here, Longfellow is lenient in describing the dikes’ effect on the landscape. Although he first characterizes the dikes as an interruption to the natural processes of land—in this case, they withhold the “turbulent tides”—he then qualifies this interruption as seasonal, after the turn of the conjunction “but.” With the verb “welcomed,” Longfellow paints this relationship between man and nature as one of friendly cohabitation; the farmers of Acadia set up these gates to hold back the waters when necessary, but the sea is happily allowed to “wander” back through when the season is over.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Family Papers, Separated Items, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS

Longfellow takes a different, but perhaps more familiar, approach to nature in his shorter narrative poem “Wreck of Hesperus.” In the poem, a skipper takes his daughter out to sea on his boat, despite a warning that a hurricane is due. His hubris ends the poem in tragedy, crafting a cautionary tale for the those that underestimate the power of nature. Consider, for example, how the daughter is first described in this stanza:

Blue were her eyes as the fairy flax,

Her cheeks like the dawn of day,

And her bosom white as the hawthorn buds,

That ope in the month of May.

At the beginning of the poem, the young skipper’s daughter is aligned with floral imagery, painting her with renewal and vivid colors of fairy flax blossoms and hawthorn buds. Fairy flax and hawthorn buds are both dainty, signifying her delicacy, but in Irish mythology hawthorn represents protection. After the storm, a fisherman finds her body still tied to the mast:

The salt sea was frozen on her breast,

The salt tears in her eyes;

And he saw her hair, like the brown sea-weed,

On the billows fall and rise.

Longfellow is perhaps pointing to the hierarchy of nature; although the daughter is initially of nature, embodying blooms of the land, she is eventually overtaken by nature more powerful—water. Her flowers shorn by the storm, the daughter is now of the sea, a brown seaweed less desirable than the blue and white blooms attributed to her earlier in the poem. Longfellow uses this imagery to warn readers of the consequences of misunderstanding their place amongst vast powers like the ocean.

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 14935)

While Longfellow was interested in retelling these stories of the past, he wrote of contemporary subjects as well. During the mid-1800s, there was a surging movement to protect birds, which were dwindling in numbers due to their popularity for hunting as game and sport, as well as for harvesting their plumes for hats.5 Women were at the forefront of this movement, like Susan Fenimore Cooper. Her book Rural Hours, published in 1850, considered the first book of nature writing to be published by an American woman.6 Writing more than a decade before Longfellow, Cooper’s content is echoed in Longfellow’s 1863 poem, “A Poet’s Tale; or The Birds of Killingworth”. Her prose even has some musicality:

“We miss our bird-companions sadly; we miss them from their haunts about our village-homes; the ear pines for their music, the eye longs for the sight of their beautiful forms flitting gayly to and fro.”

Following the success of Rural Hours, Cooper's pastoral novel The Rhyme and Reason of Country Life… by the Author of “Rural Hours” was given to Fanny Longfellow by her brother Thomas Gold Appleton for New Year’s in 1855, and can still be found in the Longfellow House collection today. However, it’s unclear if Longfellow himself ever read seminal texts like Cooper’s, although he was certainly aware of the push to protect and observe birds. On February 2nd, 1847, after thumbing through Massachusetts naturalist John James Audubon's ‘Sketches of Adventure’ and ‘Ornithology,’ Longfellow wrote in his journal: “What a miserable writer, save when he is describing birds or their habits.”7 Although harsh, his criticism of Audubon conveys how Longfellow held even nature writing to a high standard.

Longfellow addresses this blossoming conservation movement in “The Birds of Killingworth,” the final poem of Tales of a Wayside Inn, a collection of poems published in 1863, structured similar to Geoffrey Chaucer’s Cantebury Tales. In the poem, he tells the story of a fictional New England town whose people have decided to raze their land of the birds. At a town meeting, the local schoolteacher is alone in his objections:

"What! would you rather see the incessant stir

Of insects in the windrows of the hay,

And hear the locust and the grasshopper

Their melancholy hurdy-gurdies play?”

The schoolteacher argues with the logic of ecology, implying the natural order of less birds means more insects, and that the townspeople’s plans are shortsighted. The schoolteacher desperately asks his neighbors:

"Do you ne'er think what wondrous beings these?

Do you ne'er think who made them and who taught

The dialect they speak, where melodies

Alone are the interpreters of thought?Whose household words are songs in many keys,

Sweeter than instrument of man e'er caught!

Whose habitations in the tree-tops even

Are half-way houses on the road to heaven!

Longfellow likens the birds to beings that can bring humans closer to God. They are the ones “on the road to heaven,” harboring an innate holiness that man must seek and respect. Only by listening to their “melodies” and “songs" can humans achieve some sense of enlightenment.

Longfellow drives this point through the rest of the poem; the schoolteacher’s pleas are dismissed, and the townspeople eventually succeed in killing and driving out the birds from their town, but eventually suffer under the loss of the birds. Without birds, the prophetic schoolteacher’s predictions are fulfilled; the days behind scorching hot, insects overrun the orchards, and the greenery withers. Longfellow harshly condemns the townspeople for their actions:

Devoured by worms, like Herod, was the town,

Because, like Herod, it had ruthlessly

Slaughtered the Innocents.

Ultimately, the townspeople admit their mistake and import new birds who bring order and song to Killingworth again, leaving the readers to consider their own role in the natural world. Longfellow asks people to think about the consequences of their actions on the land and its organisms, pointing out what they can provide for us. Ultimately, these flora and fauna are not a resource to exploit, but to enjoy.

NPS photo

Through his lyric poetry, Longfellow reveals the range of beliefs he has about the relationship between nature and humans. In “Flowers” (1839), Longfellow demonstrates the wisdom embedded in all forms of nature by equating the small blooms of the earth with stars of the sky. Longfellow upholds that the flowers are “stars, that in the earth’s firmament do shine.” This holy, sacred quality of flowers is important to set up for later in the poem:

In all places, then, and in all seasons,

Flowers expand their light and soul-like wings,

Teaching us, by most persuasive reasons,

How akin they are to human thingsAnd with childlike, credulous affection,

We behold their tender buds expand;

Emblems of our own great resurrection,

Emblems of the bright and better land.

Using flowers as a proxy to stars, Longfellow makes the link between humans and heaven more accessible. Recognizing themselves in flowers, Longfellow explains, humans can better understand the beauty of their own existence, too.

The relationship between human and nature is even more reciprocal in his poem “Woods in Winter” (1839), which follows the narrator’s walks through the woods in the wintertime. At first, the narrator paints a demure scene of winter with imagery like the “lonely vale,” “barren oak,” “frozen urns.” By the last stanza, however, the narrator has come to accept the sensations of his cold walk:

Chill airs and wintry winds! my ear

Has grown familiar with your song;

I hear it in the opening year,

I listen, and it cheers me long.

After the narrator becomes “familiar” enough with the woods to address it directly, that communication is reciprocated by the woods. The wood now “cheers” and supports the narrator. Through this short poem, Longfellow invites readers to consider the benefits of befriending nature by accepting and working parallel to its seasonal changes.

This theme resonates through many of Longfellow's poems: What does nature give us? What can we give nature? Longfellow proposes his answers to these questions; if you work to close read his stanzas, the poems reveal as much.

The harder work, then, is unveiling our own answers to these questions and reflecting on what we believe is our place in the world.

-Pauline Ordonez, 2021

Part of a series of articles titled Of Poetry and Nature: Longfellow's Green Rhyme and Verse.

Previous: Longfellow's Environmental Niche

Next: Nature Poetry Resources

Last updated: October 29, 2021