NPS Photo, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Dana papers, LONG collections

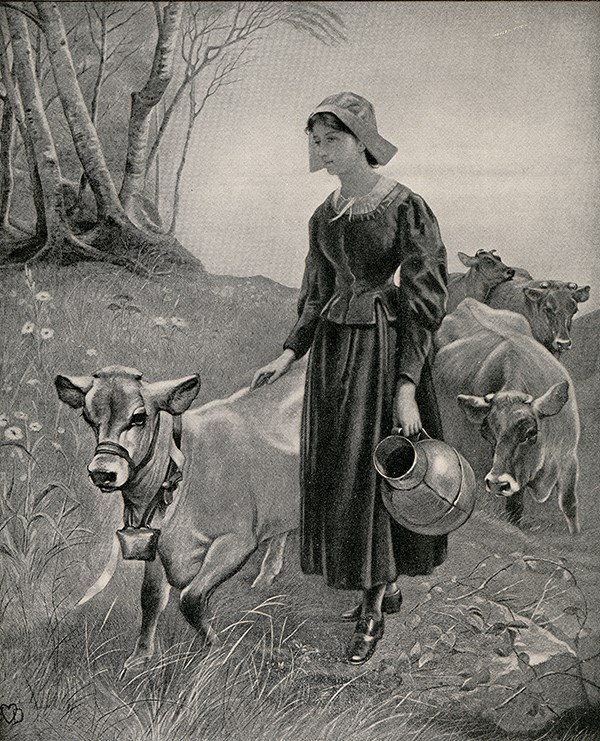

NPS Photo, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Dana papers, LONG collections Longfellow - Professor and PoetHenry Wadsworth Longfellow began writing the “idyl in hexameters” which would become Evangeline in November of 1845, shortly after the birth of his second child. He was a respected professor who had been teaching foreign languages at Harvard for almost ten years, and a published author and translator fluent in many European languages, classical Greek, and Latin. He had recently married his second wife, the wealthy and beautiful Fanny Appleton, and the two were living in the impressive Cambridge mansion known locally as the Craigie House. The Story of EvangelineEvangeline: A Tale of Acadie tells the story, in unrhymed verse, of the young and beautiful Evangeline and the noble Gabriel Lajeunesse, childhood friends living in Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia. The two are members of a peaceful farming community that embodies all the values of virtuous rural life held dear by the Victorian audience for whom the poem was written. They are engaged to be married, but are almost immediately separated when their entire community is forced into exile. Following the harrowing scene of their ejection, Evangeline spends the rest of her life traveling throughout North America, hoping to be reunited with her one true love. Only after many years of fruitless searching does Evangeline find Gabriel, on his deathbed. After a moment of mutual recognition, Gabriel dies, held by Evangeline as she thanks God for bringing them together one last time. The poem concludes with the assurance that the two lovers, are buried side by side, together for eternity, with Evangeline’s devotion to be celebrated in the land of their birth forever. Historical Background of EvangelineThe fictional Evangeline and Gabriel’s story of thwarted love is told against the backdrop of a real historical event: the expulsion of the French-speaking Acadian people from Nova Scotia by the British. As a life-long New Englander, it is likely that Longfellow had some familiarity with this history, although the extent of his early knowledge is unclear. By the time he began writing Evangeline, he had read much of the available information about the incident, in particular historical accounts by Judge Thomas Chandler Halliburton and Abbe Raynal, who painted a picture of an idyllic pre-exile Acadian life that greatly influenced Longfellow’s own depiction. Nova Scotia was part of a larger French-speaking region known as Acadia that also included Quebec, New Brunswick, and the region that would become the state of Maine. The expulsion, known to the French speaking Acadians as le grand dérangement, began in 1755 when British officials decided to tighten their grip on the territory. The British entered towns in the region, asked the local Acadians to swear allegiance to the British crown, and forcibly removed them when they refused to do so. While some of these displaced people eventually found their way back to Nova Scotia, most settled in various locations in North America. The most well-known of the resulting communities are the Cajuns of Louisiana. Inspiration for the Writing of EvangelineLongfellow credited Nathaniel Hawthorne and “his friend from Salem” (letter from HWL to James Fields, 1870) with giving him the inspiration for the story of Evangeline. Longfellow and Hawthorne, former college classmates, became close friends after their college days. They met frequently, as the always sociable Longfellow included Hawthorne in his circle of literary and academic companions. On one such occasion, probably in 1840 or 1841, Hawthorne brought his friend, Reverend Horace L. Conolly, to dinner at Longfellow’s house. Conolly spoke of a legend that one of his parishioners had told him about a displaced Acadian woman spending her entire life traveling in search of her lost lover. Longfellow was intrigued by Conolly’s narrative and a bit incredulous to hear that Hawthorne was disinterested in it as a story topic. When Hawthorne insisted of Conolly’s legend “It is not in my vein,” Longfellow asked if he could use it himself. Hawthorne consented. However, several years followed before Longfellow actually commenced writing.

NPS Photo, LONG collections, LONG 7225. Form Follows Function - Evangeline as a Work of Epic LiteratureEvangeline is a poem with an epic scope. Its protagonist spends decades searching for her lost lover, traveling a route created by Longfellow that encompasses a large part of what was the United States and its territories. Longfellow initially planned to write a shorter poem, to include an expansive description of the idyllic, pre-expulsion life in Acadia, segueing into the tragic closing death-bed scene with Gabriel in Philadelphia. But by the time he had finished writing the final scene, Longfellow decided to expand the range of Evangeline’s travels and added details of her trek down the Mississippi, through Louisiana and across the western prairies in search of Gabriel. Longfellow saw this story in terms of an heroic odyssey, even before including the details of Evangeline’s decades-long journey. He is quoted as saying that this story was “the best illustration of faithfulness and constancy of woman that I ever heard of” according to Horace Conolly. As a student of world literatures, Longfellow was well aware of the traditions of epic narratives in other languages and of the perception that the United States, not yet one hundred years old as a country, had not produced any truly worthwhile literature of its own. Perhaps this influenced him in his conception of Evangeline as an epic saga. He knew he wanted to tell this story using dactylic hexameters, a form of meter in poetry most often associated with Greek and Latin epics such as Homer’s Illiad. While many others – including his wife Fanny and his close friend Charles Sumner - questioned his choice to use a meter with which many English speaking readers would not be familiar, Longfellow never deviated from his own opinion. As he wrote in his journal, “To me it seems the only one for such a poem.”

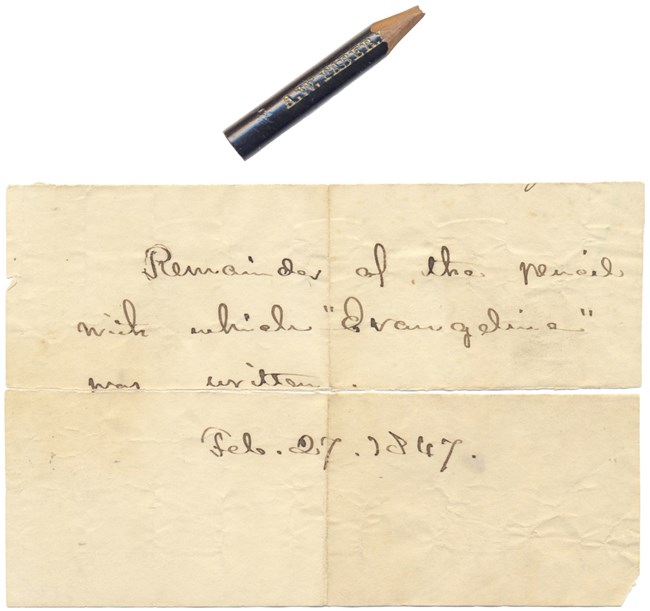

Museum Collection (LONG 24908) Publication and Critical ReactionLongfellow competed his first draft of Evangeline on his fortieth birthday, February 27, 1847. The poem underwent several months of review and revision before being published on November 1st. While Longfellow did his writing alone, he welcomed collaboration in this final polishing stage, relying upon local friends whose opinion he valued and whom he felt understood what he was trying to achieve with the poem. Future U.S. Senator Charles Sumner, Professor Cornelius Felton, and librarian and scholar Charles Folsom all received “proofs” of the poem as it was being readied for publication. Felton and Folsom, in particular, had a great deal of input into the final draft. Felton was a classical scholar who made sure that every line of Evangeline was a true hexameter. Folsom was a detail oriented perfectionist who challenged descriptions of weather, topography, foliage, and characterization with a zeal that would have annoyed a less collegially-minded author. But Longfellow appears to have welcomed the input. By the end of the summer of 1847 Evangeline was ready for publication. Longfellow was already a well-regarded poet when Evangeline was published and the public embraced the poem almost immediately. Critics were not always as kind; some reviews were very favorable while others criticized the form, finding hexameter pretentious, awkward, and inappropriate for an English poem. Some critics questioned the originality of the story or found the character of Evangeline to be banal or unrealistic. Regardless of the critics, Longfellow’s Evangeline resonated with many readers. The poem was reprinted continually throughout the nineteenth century and translated into many other languages. With its publication, Longfellow became America’s most beloved poet of the nineteenth century.

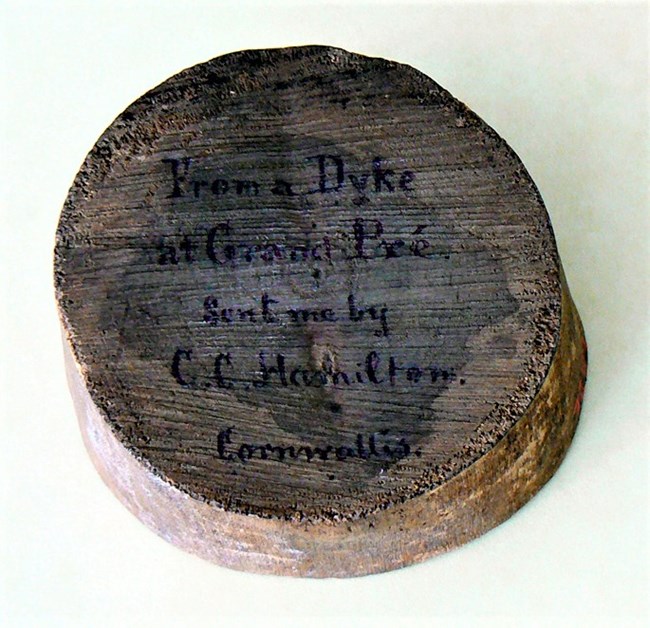

NPS Photo, LONG collections, LONG 7209. Continuing Influence of EvangelineEvangeline was a sensation when it was published and it remained popular for decades. Enthralled fans were still asking Longfellow twenty-five years after the poem’s first publication, “Will you please tell me who was Evangeline?” Others sent him artifacts that they saw as connected in some way to the story. Books were written purporting to be the story of the “real” Evangeline and movies were made, the most popular starring Delores Del Rio in 1929. Perhaps most significantly, the culture of the Acadian people experienced a renaissance as they identified with and felt vindicated by the public’s new-found sympathy with their under-appreciated tragic history. Acadians who had returned to Nova Scotia felt a newborn ethnic pride, as did the Cajun people of Louisiana. Evangeline became a popular name for locations, businesses and products. Statues of Evangeline were erected in St. Martinville, Louisiana and Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia. Travel brochures and postcards proudly cited their real or imagined connection to Evangeline, hoping to profit from an association with the Acadian heroine. Many of these names remain, evoking a poem and a heroine that people outside of the Acadian diaspora have forgotten. Research continues into the history of le grand dérangement and scholars still disagree as to how Longfellow’s poem should be understood in terms of the historical events. But there is no denying that Longfellow’s poem gave a voice and a popular narrative to a people who had been essentially forgotten. Evangeline memorialized an event of notable significance to the Acadian people. In turn, Acadians have given Evangeline an enduring pride of place in their culture, ensuring that Longfellow’s work will not be forgotten. |

Last updated: February 20, 2025