Last updated: February 20, 2026

Article

Lafayette in Boston

I joyfully anticipate the day, not very remote, thank God, when I may revisit the glorious cradle of American, and in the future, I hope, of universal liberty.

Massachusetts Historical Society

Americans have long respected and honored Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, the man more commonly known as the Marquis de Lafayette, or simply Lafayette.[1] As a skillful military leader, he led his soldiers in battle. He effectively served as a diplomat and advised the French government to channel aid to American colonial forces. Lafayette also earned his reputation as a war hero, becoming a symbol of the Revolutionary War generation who helped create the United States.

For generations, Americans have expressed their gratitude to Lafayette. Some towns have dedicated memorials to him, and even over 150 towns and locations have been named in his honor. One city that has deep ties to Lafayette is Boston.

The Cradle of Liberty

By the time of Lafayette’s first visit to Boston in August 1778, he had already participated in four military engagements with the Continental Army against British forces. Earlier in July 1777, Lafayette had travelled from France to the American colonies for the first time and at his own expense. He received a commission as a major general in the Continental Army from the Continental Congress in Philadelphia; he was 20 years old.

Lafayette had strong ties to Boston that lasted for nearly 50 years, starting in 1778 and ending in 1825. He contributed to the longstanding American-French relationship that centered in Boston. Lafayette traveled to Boston on five occasions as he performed his military and diplomatic missions. He visited Boston an additional three times as a war hero.

This chronology of Lafayette’s relationship with Bostonians and their town shows that it was based on the passion each had for the cause of American independence.

Boston Public Library

1778

American colonists and the French military had their first joint venture against the British in 1778. The French and the Americans planned to attack the British at Newport, Rhode Island, by land and sea. According to this plan, a large French naval fleet, under Admiral Comte d’Estaing, would first land French soldiers near Newport and then engage British navy ships in battle. Meanwhile, Lafayette would lead a force of colonial and French soldiers on land.

Unfortunately, a severe storm ended the French plans to fight the British at Newport. The storm damaged several of d’Estaing’s ships and he retreated to nearby Boston to get his ships repaired. However, the land battle continued near Newport. With no joint French and colonial force to lead there, Lafayette instead travelled to Boston to explore the possibility that some of d’Estaing’s military force could return to Newport and resume the fight against the British. D’Estaing and Lafayette could not work out a plan for the French to return to Newport.

The British won the Battle of Rhode Island, also known as the Siege of Newport. Lafayette returned to the Newport area from Boston. He had missed some of the fighting, but he assisted in the retreat of the Continental Army from Newport.

NPS Photo

Lafayette met again with Admiral d’Estaing in Boston in late September 1778 at d’Estaing’s request. A French officer, part of d’Estaing’s fleet, had been killed on a Boston street earlier that month. Anti-French feeling among some Bostonians may have led to the officer’s death. Anti-French sentiment could disrupt the Treaty of Alliance signed in Paris earlier that year between the French and the Americans.

Lafayette, d’Estaing, and Boston leaders attributed the officer’s murder to dockside rowdyism and not to anti-French feelings in Boston. Lafayette’s role in resolving the French officer’s death in this way helped preserve the Franco-American alliance.

Though there may have been some anti-French feeling in Boston, many Bostonians were supportive of the French fleet. Boston shipbuilders completed the repairs of d’Estaing’s fleet in four months, faster than expected. The fleet then sailed to the Caribbean to confront the British navy there.

After his second visit to Boston in late September 1778, Lafayette travelled to Philadelphia in early October 1778 to meet with the Continental Congress. He informed the Congress that he planned to travel to France to meet with French authorities to encourage military and financial aid to the Americans. Lafayette fell ill, delaying his trip to France. He stayed with friends in Fishkill, New York, for a few months and returned to Boston in early January 1779.

1779

Lafayette came back to Boston in January of 1779. Here, he boarded the French frigate L’Alliance, which took him to France. Lafayette planned to meet with French authorities to secure a commitment to bring about 6,000 French soldiers to America. Lafayette succeeded in this mission and returned to Boston in April of 1780.

Courtesy Eleanor Beardsley/NPR

1780

Lafayette arrived in Boston on April 28, 1780, aboard the L’Hermione after his fruitful trip to France. Here, Lafayette "produced the liveliest sensation...Every person ran to the shore; he was received with the loudest acclamations and carried in triumph to the house of Governor Hancock."[2] On May 2, Lafayette left Boston for Washington’s headquarters in Morristown, New Jersey, with the good news that the French government would send French forces to aid Washington.

1781

Lafayette successfully led military forces at Yorktown, Virginia, and contributed to the overall defeat of the British on October 19, 1781. The American War of Independence was nearly over. Lafayette decided to return to France and planned to depart from Boston on board the L’Alliance. Lafayette addressed Bostonians at the Boston Town Meeting on December 14, 1781, with obvious affection:

"To have been admitted among you from an early period, in the defense of the cause of liberty will forever be the happiest circumstance in my life. But it becomes more particularly so, when it is so kindly remembered by those who first began the Noble Contest, and who have ever since been so conspicuous in its support.

Nothing could induce me to leave this continent even for a short period, before I had the satisfaction to see my friends in this town — Be pleased gentlemen to accept my most respectful acknowledgements to your good wishes. The height of my ambition would be, and particularly, to gratify those affectionate sentiments which forever devote me to this Metropolis."[3]

Library of Congress

1784

Lafayette visited the United States for a 5-month stay, August to December, in 1784. With this trip, Lafayette celebrated the Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution in 1783. He also planned to establish French commercial and diplomatic interests in the US. Lafayette visited George Washington at Mount Vernon, probably a highlight of the trip.

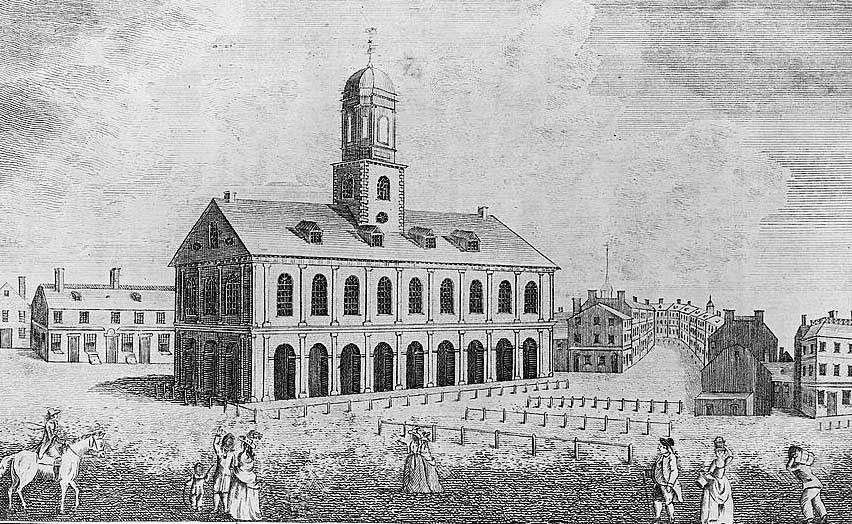

Lafayette visited Boston in October 1784. Massachusetts Governor John Hancock, Boston merchants, and others dined with Lafayette in Faneuil Hall. The merchants honored Lafayette with a 13-gun salute accompanied by drinking toasts. Lafayette also received an Honorary Degree at Harvard University during this trip.

1824

US President Monroe invited Lafayette to a grand tour of the United States, which consisted of 24 states at the time. Congress awarded Lafayette $200,000 and over twenty-thousand acres of land in Florida. Monroe wished to commemorate the US centennial with the only American Revolutionary War general still surviving, the Marquis de Lafayette. 67 years old at the time, Lafayette continued to be much-beloved by the American public.

Lafayette visited Boston from August 25 to September 2, 1824. Over 100,000 people greeted Lafayette when he arrived in Boston. Lafayette visited Harvard University, the Charlestown Navy Yard, the site of the Battle of Bunker Hill, and the site of the Battle of Lexington and Concord. He also watched a mock Revolutionary War battle on the Boston Common. Bostonians hosted numerous dinners and parties in his honor. Lafayette also visited former US President John Adams in nearby Quincy.

Boston Public Library

1825

After he left Boston in September 1824, Lafayette continued his grand tour of the US. He travelled over 5,000 miles before returning to Boston in June 1825. On this visit, Lafayette helped lay the cornerstone for the future Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown, Massachusetts, near Boston.

This large ceremony on June 17, 1825, marked the 50th anniversary of the famous battle and was attended by 200,000 people. Lafayette addressed the crowd: "Bunker Hill is the holy resistance to oppression, which has already disenthralled the American hemisphere, and the anniversary toast at the jubilee of the next half-century will be to Europe, freed."[4]

Lafayette paid another visit to John Adams in Quincy during this time. He left for France from Washington, DC, after meeting with the son of John Adams, John Quincy Adams, then the US President in 1825.

1834

Lafayette’s grand tour in 1824-1825 did not end Lafayette’s relationship with Boston. When Lafayette died in 1834, his son sprinkled soil from Bunker Hill on Lafayette’s grave. Lafayette had collected the soil during his Boston visit in 1824. Americans mourned Lafayette across the US. The Boston City Council asked Bostonians to wear a black arm band for thirty days to mourn the loss of Lafayette.

1924

In 1924, Bostonians installed a bronze plaque honoring Lafayette on the Boston Common in the center of the city. The memorial marks the centennial of Lafayette’s visit to Boston in 1824. The memorial honors Lafayette for marshalling French support for American independence.

Boston Public Library

Merci Lafayette

Lafayette’s two visits to Boston in 1778 were probably his most challenging diplomatic visits to the town. He resolved conflicting French and American interests as these two allies faced a common enemy, the British.

His trip to Boston in December of 1781, however, was perhaps the most emotional visit. Lafayette had recently left the battlefield at Yorktown, Virginia, where he had led a successful assault against British forces. Boston officials in their town meeting of December 14, 1781, praised Lafayette. Lafayette was in Boston but probably not at the meeting:

"Your sacrifice of domestic enjoyment to the cause of God and Humanity---your generous excursions in a foreign country in support of that cause and the success which has crowned those exertions, so dangerous to your own person, have in the opinion of the town, added a luster to your exalted rank and give you a name and a place in the first lists of American patriots and heroes."[5]

Lafayette and the Bostonians had a mutual affection for each other that still resonates these many years later.

Footnotes

[1] The above quote is from: Dr. Edward Hartwell, “Lafayette and Boston,” City Record, Official Publication of the City of Boston, May 19, 1917, 518.

[2] Kim Burdick, “Lafayette’s Second Voyage to America: Lafayette and L’Hermione,” Journal of the American Revolution, April 20, 2015, accessed December 28, 2025.

[3] Hartwell, “Lafayette and Boston,” 518.

[4] Hartwell, “Lafayette and Boston,” 518.

[5] Hartwell, “Lafayette and Boston,” 836.

Sources

"150 Places in America Named After Lafayette; 5,000 with Names of French Origin are Listed." New York Times, 14 Sept. 1930, p. 33. ProQuest. Web. 29 Dec. 2025.

Balch, Thomas. The French in America during the War of Independence of the US. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1891.

Brown, Abram English. Faneuil Hall and Faneuil Hall Market. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1900.

Burdick, Kim. “Lafayette’s Second Voyage to America: Lafayette and L’Hermione.” Journal of the American Revolution. April 20, 2015. Accessed December 28, 2025.

Clarke, Jeffrey J. March to Victory: Washington, Rochambeau, and the Yorktown Campaign of 1781. US Army Center of Military History, 2015.

“Fete Lafayette, A French Hero’s Tour of the American Republic.” American Revolution Institute. Accessed December 31, 2025.

Hartwell, Dr. Edward M. “Lafayette and Boston,” City Record, Official Publication of the City of Boston, May 19, 1917.

Happ, John E. “Lafayette, the American Experience.” Journal of the American Revolution. August 30, 2017. Accessed November 19, 2025.

“Lafayette Souvenir Glove.” Collections Online, Massachusetts Historical Society. Accessed January 18, 2026.

Maguire, Peter. “General Lafayette, The Nation’s Guest, comes to Boston and Stops for Lunch in Reading.” The Reading Post. May 12, 2021. Accessed December 28, 2025.

“Major General Lafayette to George Washington, 21 September 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 17, 15 September–31 October 1778, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008, pp. 69–72.]

“Major General Lafayette to George Washington, 24 September 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 17, 15 September–31 October 1778, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008, pp. 118–119.]

Mark, Harrison W. “Battle of Rhode Island.” World History Encyclopedia. March 25, 2024. Accessed January 14, 2026.

“Marquis de Lafayette.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Accessed December 28, 2025.

“Marquis de Lafayette.” Collections Online, Massachusetts Historical Society. Accessed January 18, 2026.

Schmidt, Gloria. “Lafayette in Rhode Island.” The Battle of Rhode Island Association. Accessed December 28, 2025.

Smith, Fitz-Henry Jr. The French at Boston During the Revolution. Boston: Privately Printed, 1913.

“October 19: Surrender at Yorktown.” Today in History, Library of Congress.

"The Battle of Rhode Island." Tiverton Historical Society. Accessed November 19, 2025.

“The Guest of the nation: the Marquis de Lafayette’s tour of the United States, 1824-1825.” Object of the Month, Massachusetts Historical Society. August 2024. Accessed December 28, 2025.

“The Marquis de Lafayette.” Lafayette College. Accessed September 21, 2025.

Webb, Olivia. “Learning about Lafayette: America’s French War Hero.” James Monroe Museum. April 24, 2024. Accessed January 14, 2026.

Welsh, William E. “French Vice Admiral Charles d’Estaing.” Warfare History Network. Fall 2022. Accessed December 31, 2025.