Left image

Right image

Minute Man National Historical Park in Lexington, Lincoln, and Concord, Massachusetts, preserves and interprets the sites, structures, and landscapes that became the field of battle during the first armed conflict of the American Revolution on April 19, 1775. It was here that British colonists risked their lives and property, defending their ideals of liberty and self-determination. The events of that day have been popularized by succeeding generations as the "shot heard 'round the world." Often referred to as the "Battles of Lexington, and Concord," the fighting on April 19, 1775 raged over 16 miles along the Bay Road from Boston to Concord, and included some 1,700 British regulars and over 4,000 Colonial militia.

British Casualties totaled 273; 73 Killed, 174 wounded, 26 missing. Colonial casualties totaled 95; 49 killed, 41 wounded, and 5 missing. Quick Links

Battle Site Explorations

At Minute Man, we use history, living history, science and technology to help us learn about the past.

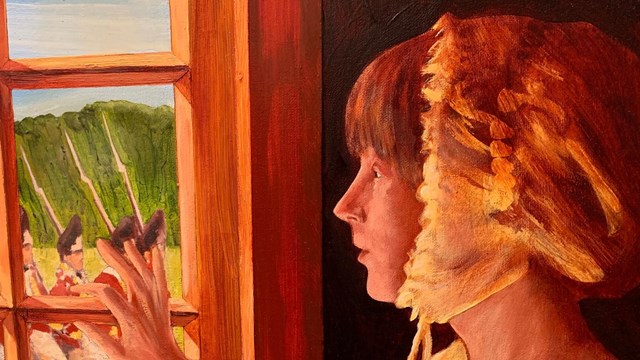

April 19, 1775 Witness Houses

Learn about the many April 19, 1775 witness houses at Minute Man!

The Militia and Minute Men of 1775

Ranger Jim provides some basic information about the militia and minute men of 1775.

The British Soldier of 1775

Here you will find quick and useful information about the British soldiers in 1775.

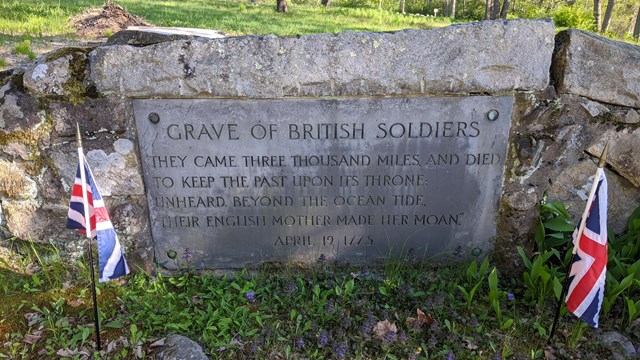

Grave Sites

Minute Man National Historical Park is both a battlefield and graveyard. Many soldiers killed during the battle remain within the park today

People

Learn about the people whose lives we commemorate at Minute Man. Overview of BattlePrelude to War~ April 18, 1775In the days, weeks, and months leading to April 19, 1775, tensions across the colony of Massachusetts reached a boiling point. The previous summer British warships closed Boston Harbor, Royal Governor, General Thomas Gage, tasked with implementing the wildly unpopular Massachusetts Government Act, also dismissed the elected Massachusetts legislature, the Great and General Court. In October Patriot leaders called for a Provincial Congress in Massachusetts. Towns across Massachusetts chose to send representatives to this essentially illegal body which immediately proceeded to assume political power. They took control of the colony's militia forces, and began stockpiling arms, ammunition and provisions. Their goal was to raise and equip an army of 15,000 men. April 19, 1775The Regulars are out! Solomon Brown, a young man of Lexington who had been to market in Boston, arrived home with the news that he overtook and passed a patrol of British officers on the Bay Road. Brown reported his observations to Sergeant William Munroe, proprietor of the Munroe Tavern.

Alarmed by the British excursion into the countryside, Munroe collected eight men from his militia company and posted a guard at the Hancock-Clarke House where John Hancock, and Samuel Adams were then lodging. Deposition of William Munroe, March 7, 1825 Near 8:00 P.M. a party of mounted British officers’ rode through Lexington without attempting to arrest Hancock and Adams. Although observed by locals, the patrol continued along the Bay Road toward Lincoln, passing the area of Hartwell Tavern. As soon as the British patrol exited Lexington, about 40 militia gathered at the Buckman Tavern on Lexington Green to plan their next move.

After passing the farmhouse of Sergeant Samuel Hartwell of the Lincoln Minute Men, the British officers wheeled about and rode back toward Lexington looking for an ideal place to establish a checkpoint. Deposition of William Munroe, March 7, 1825 Near 9:00 P.M. the Lexington militia decided to send scouts mounted on horseback to watch the movements of the British patrol. Elijah Sanderson, later a famous Salem cabinet maker, Jonathan Loring, and Solomon Brown, who had first spotted the horsemen, volunteered.

The group departed Lexington center headed toward Lincoln, unaware of an impending British trap. After crossing the Lincoln line and continuing for nearly a mile, the British patrol emerged from a woodlot and seized the party at pistol point. The militiamen were then led into a pasture and held for four hours, preventing them from spreading the alarm. Lemuel Shattuck, A history of the town of Concord, Boston: Russell, Oriorne, and Company, 1835, 102. General Thomas Gage, Royal Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, to Lt. Colonel Francis Smith of His Majesty's 10th Regiment of Foot

"Sir, Having received intelligence, that a quantity of Ammunition, Provision, Artillery, Tens and small arms, have been collected at Concord for the Avowed Purpose of raising and supporting a Rebellion against His Majesty, you will march with the Corps of Grenadiers and Light Infantry put under your command, with the utmost expedition and secrecy to Concord, where you will seize and destroy all artillery, Ammunition, Provisions, Tents, Small Arms, and all Military Stores whatever. But you will take care that the Soldiers do not plunder the inhabitants, or hurt private property." With these orders, Smith was to take roughly 700 soldiers on an 18-mile march into the hostile Massachusetts countryside, seize and destroy rebel military supplies, then return that day to Boston (36 miles round trip). The grenadiers and light infantry in Boston, "were not apprised of the design, till just as it was time to march, they were waked by the sergeants putting their hands on them and whispering to them." But Dr. Joseph Warren had the news almost before the British left their encampment. He sent for two trusted men, Paul Revere and William Dawes Jr. Concerned about the route of the British march, Warren dispatched Dawes over the longer route, to Lexington via Boston Neck, Roxbury, Brookline, Cambridge and Menotomy (Arlington). Revere planned to row across the Charles River and then proceed through Menotomy to Lexington. Ultimately the pair planned to meet in Lexington and warn John Hancock and Samuel Adams who were staying there during a recess of the Provincial Congress. From there the alarm riders would continue towards Concord. “Paul Revere’s three accounts of the Day.” in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” 2:183.; Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride,110-111. Passing silently by the British warship Sommerset, Paul Revere landed safely in Charlestown where Colonel Conant, a member of the Committee of Safety met Revere. Conant confirmed that he had seen the lanterns and dispatched messengers already.

The lantern signals were a pre-arranged signal. According to Paul Revere himself, "When I got to Dr. Warren’s house, I found he had sent an express by land to Lexington — a Mr. William Daws [Dawes]. The Sunday before.I agreed with a Colonel Conant and some other gentlemen that if the British went out by water, we would show two lanthorns in the North Church steeple; and if by land, one, as a signal; for we were apprehensive it would be difficult to cross the Charles River or get over Boston Neck. I left Dr. Warren, called upon a friend and desired him to make the signals." Revere mounted a horse and began his journey to Lexington. “Paul Revere’s three accounts of the Day.” in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” 2:183.; Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride. "Between 10 and 11 o'clock all the Grenadiers and Light Infantry of army...embarked and were landed upon the opposite shore on Cambridge marsh; few but the commanding officers knew what expedition we were going upon. After getting over the marsh where we were wet up to the knees, we were halted in a dirty road and stood there 'till two o'clock in the morning waiting for provisions to be brought from the boats and be divided, and which most of the men threw away, having carried some 'em. At 2 o'clock we began our march..." Lt. John Barker, 4th Regiment of Foot, King's Own

Revere and Dawes rendezvoused in Lexington to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock at the home of the town's minister, Reverend Jonas Clarke. When Revere started shouting under the bedchamber window, Sergeant Munroe of the Lexington Militia told him to not make so much noise. Revere replied "You'll have noise enough before long! The Regulars are coming!" Having warned Adams and Hancock, Revere and Dawes then determined to continue their ride to Concord and warn every household along the way. Soon after starting for Concord, they met Dr. Samuel Prescott of Concord who agreed to ride with them and help. Captain Parker, commander of the Lexington militia, mustered his company on the town green.

Deposition of William Munroe, March 7, 1825; “Paul Revere’s three accounts of the Day.” in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” 2:183. Paul Revere was riding about 200 yards ahead of William Dawes and Samuel Prescott when two mounted British officers suddenly appear from an opening in a wall that led into a pasture. Dawes turned his horse and fled back toward Lexington to escape. Prescott jumped his horse over a fence, evaded capture and made it to Concord. Revere cut into the pasture only to be stopped by 6 other British officers. Holding up a pistol, one of them yelled “Stop, or I’ll blow your brains out!”

The officers questioned Revere at pistol point; but undaunted Revere exclaimed “You have missed your aim!” meaning the guns at Concord. He then told them he had alarmed the countryside, and that militia would soon oppose the regulars march. Deposition of William Munroe, March 7, 1825; “Paul Revere’s three accounts of the Day.” in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” 2:183. “This morning between 1 & 2 O’clock we were alarmed by the ringing of ye bell, and upon examination found that ye troops, to ye number of 800, had stole their march from Boston in boats and barges, from ye bottom of ye common over to a point in Cambridge...This intelligence was brought us at first by Samuel Prescott who narrowly escaped the guard that were sent before on horses purposely to prevent all posts and messengers from giving us timely information....” Reverend William Emerson of Concord.

Once the bells sounded, Concord immediately turned out its two minute companies and two militia companies. The men mustered at the town center near the meeting house. Colonel James Barrett was responsible for safeguarding the military stockpiles in town and began detaching men from their companies to assist in removing or hiding any of the stores that had not already been removed a few days prior. Meanwhile in Lexington, Captain Parker dismissed his company with orders to be ready to assemble at the beating of the drum. Those who did not live near the town green spent a nervous night in Buckman Tavern. The ferrying of 700 British soldiers across the Charles River took nearly three hours to complete. Further delays to distribute food in the form of hard-baked biscuits left the men waiting along the riverbank in wet wool, under a full moon in 36-degree weather. By 2:00 am the soldiers were miserable and tired even before column started to move. As the regulars departed for Concord, the sounds of alarm resonated across the countryside: bells ringing and guns firing. Any hope they had of secrecy was lost.

Account of Lt. John Barker, 4th Regiment of Foot, King's Own in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” Near 2:30 am The British patrol that captured Paul Revere lead him and three other captured militia scouts back toward Lexington. When they heard alarm gunfire, the British officers decided it would be best to set their prisoners free (without their horses) and try to link up with the column marching from Cambridge. Revere made his way across “a burying ground and some pastures” to the home of Reverend Clarke where he helped John Hancock and Samuel Adams prepare to evacuate.

“Paul Revere’s three accounts of the Day.” in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” 2:183. Colonel Azor Orne, Colonel Jeremiah Lee and Elbridge Gerry, all members of the Committee of Safety from Marblehead, were staying at the Black Horse Tavern in Menotomy (today Arlington). Upon seeing the British column march by the men escaped out the back door of the tavern into the chilly April air still in their nightclothes. They hid in a field of corn stubble until the Regulars passed.

The orders that General Gage gave to Lt. Colonel Francis Smith were to march to Concord to seize arms and supplies. They made no mention of arresting political leaders. However, such an action was generally feared by the Patriot leadership. After passing through Menotomy the severity of the Regular’s situation sunk in. Acting as a scout ahead of the column Lt. William Sutherland of the 38th Regiment of foot recounted he “saw a vast number of Country Militia going over the Hill with their Arms to Lexington.” Letter of William Sutherland to Sir Henry Clinton, in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,”; Memoirs of Major-General William Heath: containing anecdotes, details of skirmished, battles, and other military events during the American War, (Boston: J. Thomas and E.T. Andrews, 1798),5. On the outskirts of Menotomy the Regular column split into two sections. Fearing for the success of their mission Lt. Col. Francis Smith detached around 200 Light Infantry with instruction to rush forward to Concord and secure the important river crossings. At the same time Smith dispatched a rider back to Boston requesting reinforcements.

As the British Light Infantry approached the town of Lexington, Lt. William Sutherland recounted, “We saw shots fired to the right and left of us, but as we heard no Whissing of Balls I concluded they were to Alarm the body that was there of our approach. On coming within Gunshot of the village of Lexington a fellow from the corner of the road on the right hand Cock’d his piece at me, burnt priming, I immediately called out … to observe this Circumstance which they did& acquainted Major Pitcairn of it immediately.” In this critical moment, Major John Pitcairn commanding the detachment of Light Infantry ordered his men to stop and load their muskets. In Lexington, a scout named Thaddeus Bowman, returned in haste to warn Captain Parker that he had spotted the British column just a half mile away. Captain Parker immediately ordered his militia company to form on the green. Account of Captain John Parker, April 25, 1775 in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,”; Letter of William Sutherland to Sir Henry Clinton, in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” Lexington & Concord The British light infantry halted at Vine Brook, about a half mile from Lexington Green, to load their muskets. Continuing their advance into Lexington the Regulars soon encountered 77 men from Captain Parker’s company, forming on the town green.

Unwilling to march past the militia force, Major Pitcairn detached a few companies to push forward and confront the Lexington Militia; meanwhile the rest of the column snaked down the road on the militia flank. Accounts vary of what happened next, but most agree, a group of mounted British officers advanced toward the Militia demanding they disperse from the green and return to their homes. As a companies of light infantry from the 4th and 10th Regiments of foot deployed, Parker ordered his men to disperse. According to Lt. Sutherland of the 38th Regiment of foot the mounted officers “rode in amongst [the militia].” In the confusion, a gunshot rang out from an unknown source. Panic spread as the first company of Regulars fired a ragged volley into the dispersing Militia before the second light infantry company wheeled into line and released a second volley before rushing forward with bayonets to drive the rebels from the green. In less than three minutes the fighting concluded but resulted in the first American bloodshed of the day as eight militia were killed and ten wounded. On April 25th Captain Parker gave a sworn statement about what happened. "I...ordered our Militia to meet on the common in said Lexington, to consult what to do, and concluded not to be discovered, nor meddle or make with said Regular Troops (if they should approach) unless they should insult us; and upon their sudden approach, I immediately ordered our Militia to disperse and not to fire. Immediately said Troops made their appearance, and rushed furiously, fired upon and killed eight of our party, without receiving any provocation therefore from us." Account of Captain John Parker, April 25, 1775 in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,”; Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part II: 1-21. By dawn, minute and militia companies arrive in Concord from surrounding towns. Two companies from Lincoln joined Concord's two minute companies and two militia companies. More men from Bedford and Acton were on the way and countless other towns preparing to march. Not long after daybreak a scout, Reuben Brown, returned to Concord with news that the regulars were in Lexington, and that shots were fired. Unfortunately, when pressed further, he could not tell if they were firing "ball" (live ammunition) or if anyone had been killed.

Deposition of Nathan Barrett and others in Lemuel Shattuck, A history of the town of Concord, Boston: Russell, Oriorne, and Company, 1835, 348. Thaddeus Blood, a Private in Captain Nathan Barrett's Company was among an advanced party that marched about a mile east from the center of Concord along a high ridge that runs on the north side of the Lexington Road. There they saw the column of British soldiers, 700 strong in a column stretching about a quarter mile, marching toward them. Blood described the scene a follows:

"...we were then formed, the minute (men) on the right, & Capt. Barrett's (militia company) on the left, & marched in order to the end of Meriam's hill then so called & saw the British troops a coming down Brooks Hill. The sun was arising & shined on their arms & they made a noble appearance in their red coats & glistening arms..." Account of Thaddeus Blood, April 25, 1775 in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,”; When the regulars entered Concord, they outnumbered the militia by 3 to 1. Not wanting to bring on a general engagement the militia retreated along the ridge toward town, then over the North Bridge to a hill nearly a mile beyond called Punkatasset. There the militia waited for reinforcements to arrive from surrounding communities. In short order, the British moved to secure both the North and South bridges.

General Gage, in his orders to Lt. Colonel Smith, commander of the Britsh expedition to Concord, directed him to take control of the two bridges in town, the South Bridge and the North Bridge. "You will observe...that it will be necessary to secure the two bridges as soon as possible..." Securing the bridges was critical to prevent rebels from slipping across from remote parts of town to threaten the mission. Also, Lt. Colonel Smith sent seven companies across the North Bridge with orders to search for supplies and artillery known to be hidden at Col. Barrett's farm, about a mile west of the bridge. They left three companies (about 96 men) at the bridge to guard the important river crossing and keep the road to Barrett’s farm open. Sabin, April 19, 1775. During the winter of 1774 into 1775 the Provincial Congress assigned Militia Colonel James Barrett and Captain Jonas Heywood to manage the military supplies being gathered in Concord. On April 19, 1775 Barrett saw to both the mustering of local militia and the removal of military stores from his home in the North side of Concord. Although the rebels removed many military goods in the weeks leading up to the battle, some supplies remained at the Barrett farm. When news arrived of a British march, a train of oxen and drivers assisted Barrett’s family in removing the last goods from their property. Near 8:00 am, Colonel Barrett’s wife Rebecca and other family members were home when Captain Lawrence Parsons of the 10th Regiment of Foot arrived with a column of 120 light infantry soldiers to search the home. Rebecca obligingly served the officers breakfast while the soldiers searched the house. Ultimately the soldiers found nothing of interest on the property.

Sabin, April 19, 1775. After observing the Regulars from the safety of Punkatasset hill the militia and minute men thought best to advance to the ridge overlooking the North Bridge for a better view. When additional companies from Bedford and Acton arrived, the provincial numbers swelled to 400 men.

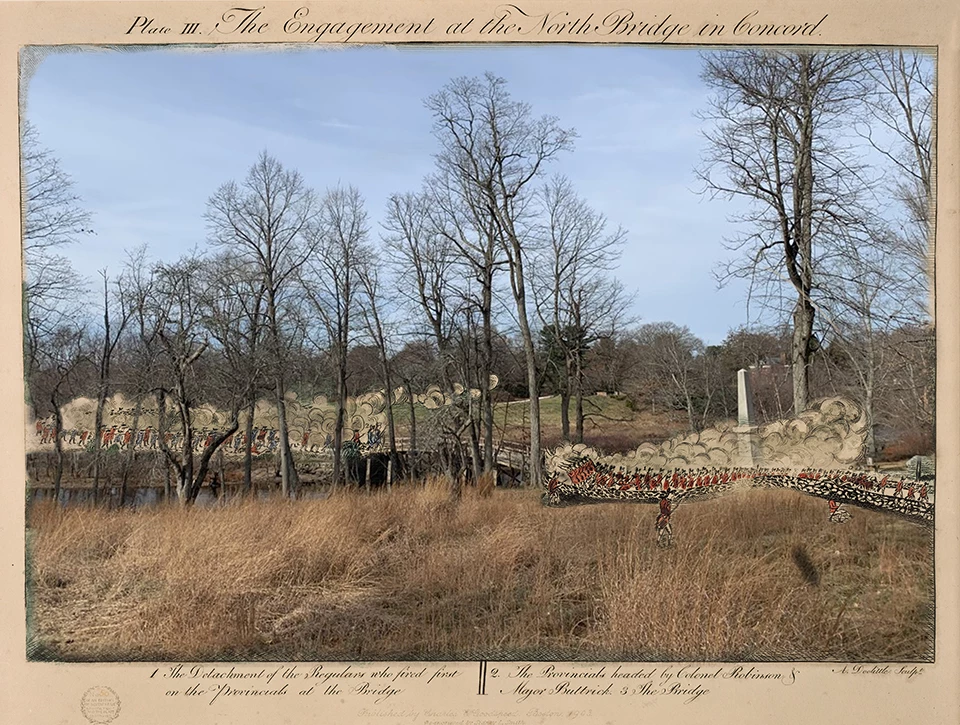

For the British companies left to guard the bridge, the militia advance pushed members of the 10th Regiment of Foot and 4th Regiment of Foot from the high ground protecting the road to Barrett’s Farm. As the Regulars withdrew back across the bridge the militia settled in on the ridge overlooking. A tense standoff prevailed. When a plume of smoke suddenly appeared above the roofs of the town the militia soldiers assumed that the Regulars were burning the town. In fact, the regulars had set fire to a pile of tents, cannon carriage parts and other supplies. When the flames accidentally spread to a townhouse, they helped extinguish the fire after an elderly widow, Martha Moulton insisted they do so. One warm-tempered Concord officer, Lt. Joseph Hosmer, exclaimed to his superiors "Will you let them burn the town down?" Following a council, the officers made the decision to march over North Bridge and proceed into the town. As the militia changed the flints in their muskets and formed to march down the long causeway to the bridge, Colonel Barrett issued a firm order. "Do not fire unless first fired upon..." With that, the column of over 400 men, minute men in front, militia companies behind, marched down the road in double file, and in good order. Sabin, April 19, 1775. Arranging themselves by seniority of companies with Minute Men at the head, each company marched by the right flank and swung into column on the causeway leading toward the bridge. Major John Buttrick (1731–1791) and Lieutenant Colonel John Robinson of Westford led the procession, followed by the Acton minutemen commanded by Captain Isaac Davis (1745–1775). In total, approximately 400 militia soldiers marched from the muster field toward the approximately 96 British troops under the command of Captain Walter Laurie guarding the bridge. When the well drilled formation of militia appeared, marching to the sound of field music, the British Regulars of the 10th and 4th Regiments withdrew entirely back to the bridge. For Laurie’s men, the encounter on the Lexington Green remained fresh in mind, and this militia advance constituted an attack.

With Militia soldiers growing closer, multiple British officers shouted contradictory orders. One officer ordered some men into the open fields flanking the bridge, while another suggested ripping up the planks of the Bridge so the militia could not cross. Captain Laurie shouted for the three companies to form a column in the roadway at the base of the bridge and prepare a street firing formation. As chaos reigned in the British ranks, the head of the Militia column arrived at the Bridge, roughly 50 yards from the British soldiers. At this point, three gunshots rang out from the British regulars, all splashing into the river harmlessly. Without an order to fire, the remaining British soldiers then commenced firing, directly into the Militia column. “The balls whistled well,” remembered one Militia soldier. At the head of the column the musketry tore through flesh and bone. Acton fifer, Luther Blanchard (1757-1775) fell wounded, shot through the throat while a musket ball struck Acton, private Abner Hosmer under the right eye, killing him instantly. At the head of the advance, Captain Isaac Davis fell, shot through the heart. Three additional militia also received wounds at the Bridge within a matter of seconds. Major John Buttrick, standing just feet from his own house issued the famed order, “Fire, for god’s sake fire!” Instantly, each militia soldier stepped into a position where they could fire on the British Regulars without the fear of hitting their own men. A hail of musketry then poured upon Laurie and the Regulars at the Bridge. Three British soldiers fell dead or mortally wounded, while nine others received lesser wounds. With the situation at the bridge unraveling quickly, many of the Regulars turned and fled back toward the town of Concord. At the Bridge, some Militia crossed over in pursuit of their retreating foe. In the area behind the home of Elisha Jones, the Regulars and pursing militia encountered a hastily gathered segment of Lt. Col. Smith’s additional forces marching from Concord center. While Colonel Smith was overseeing the search for weapons in town, he received an urgent plea from Laurie for reinforcements. Smith then ordered two companies of grenadiers to form and march in the direction of the bridge, where they met the disordered remnants of Laurie’s light infantry. Forming into position behind a stone wall, the Militia prepared for another torrent of musketry that never came. The British regulars deployed into a battalion front and dressed their battle lines, but no gunfire followed. Both forces watched and waited before the militia determined to discontinue their advance and retire back to the North Bridge and beyond. Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part III: 51 During the ensuing lull the four British companies that had searched Barrett’s property returned and passed over North Bridge; where they discovered the bodies of their comrades, one struck in the head with a bladed weapon. Unwilling to press another attack the Militia anxiously allowed the regulars to pass unchallenged. Upon rejoining the main body of British troops, those men spread word of Militia soldiers scalping the casualties at the Bridge. With tensions running high, this news brought a sense of dread and desired retribution to the regular ranks.

Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part III: 54-59. While the Regulars regrouped in Concord and tended to their wounded, the militia debated their next move. Over the next few hours, the number of Militia near the North Bridge fluctuated. Thousands of additional forces were marching on Concord from all directions. A detailed understanding of local terrain, secondary roads, and farm lanes allowed the militia to converge on Concord via multiple routes.

As the threat from arriving militia grew by the minute, Smith’s Regulars in Concord wrapped up their final searches and awaited further orders. Throughout the morning, Smith hastily scribbled off dispatches to Boston, requesting assistance. He expected a relief column of nearly 1,000 additional regulars to reinforce his return to Boston but had no word of their progress. Unfortunately, Smith did not know the planned relief column was delayed by hours. At about 12:00 p.m., Smith’s situation in Concord demanded action. With no relief in sight and thousands of Militia on the roads, the British began their retreat before any hope of escape vanished. To protect his column stretching nearly 1/3rd mile in length, Smith ordered several companies of light infantry to act as a buffer around his main body. In accordance with British military doctrine of the period, an advance guard (vanguard) posted roughly 50 yards ahead of the main body while a rear guard posted 50 yards behind. To protect the length of the column Smith rotated flanking companies on both sides of the road at 100 yards distance. This formation allowed Smith to keep hostile militia at a greater distance and ideally protect the main body of British soldiers marching on the road. Witnessing the Regulars marching from Concord, Private Thaddeus Blood, of Capt. Nathan Barrett's Concord militia company wrote, "...it was thot best to go to the east part of the Town & take them as they came back……” Sabin, April 19, 1775; Account of Thaddeus Blood, April 25, 1775 in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” Retreat Along The Battle Road Around noon on April 19, 1775, the column of approximately 700 British regular soldiers began their return march from Concord to Boston.

When the column of regulars reached Meriam's Corner, about a mile east of Concord's center, newly arrived companies of militia from Reading, Chelmsford and Billerica arrived and took cover behind the Meriam houses and barns. Reverend Edmund Foster of the Reading company recalled, "We rendezvoused near the middle of the town of Bedford, left horses, and marched forward in pursuit of the enemy. A little before we came to Merriam's hill, we discovered the enemy's flank guard, of about 80 or 100 men, who, on their retreat from Concord, kept that height of land, the main body in the road. The British troops and the Americans, at that time, were equally distant from Merriam's corner. About twenty rods short of that place, the Americans made a halt. The British marched down the hill with very slow, but steady step, without music, or a word being spoken that could be heard. Silence reigned on both sides. As soon as the British had gained the main road, and passed a small bridge near that corner, they faced about suddenly, and fired a volley of musketry upon us. They overshot ; and no one, to my knowledge, was injured by the fire. The fire was immediately returned by the Americans, and two British soldiers fell dead at a little distance from each other, in the road near the brook." Ensign Jeremy Lister, Light Infantry Company, His Majesty's 10th Regiment of Foot later wrote in his diary: "On Capt. Parsons joining us [we] begun our march toward Boston again from Concord. The Light Infantry marched over a hill above the town, the Grenadiers through the town, immediately as we descended the hill into the Road the Rebels begun a brisk for but at so great a distance it was without effect, but as they kept marching nearer when the Grenadiers found them within shot they returned their fire. Just about that time I received a shot through my right elbow joint which effectually disabled that arm. It then became a general firing upon us from all quarters, from behind hedges and walls…” As more militia poured into the crossroads the fighting intensified. Lt. Col. Francis Smith later wrote, “as we marched, [the fire] increased to a very great degree, and continued without intermission of mine minutes altogether, for, I believe, upwards of eighteen miles.” Account of Rev. Edmund Foster in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” Vol. I: 253-256.;Account of Ensign Jeremy Lister in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” Vol II: 115-119.;Report of Lt. Col. Francis Smith in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” Vol II: 73-74. As gunfire echoed from the low ground to the west, new companies of Militia arrived on the battlefield at the intersection of Brooks Road and the Bay Road on the western rise of Brooks Hill. Two companies of Minute men and Militia from East-Sudbury arrived in time to meet the British column. While marching nearly eight miles on the morning of April 19, 1775, the soldiers of Captain Nathaniel Cudworth’s minute company and Captain Joseph Smith’s militia company likely received reports from a second wave of alarm riders that directed them toward the battlefield.

Archaeological evidence discovered on the southwest side of Brooks Hill indicates the fighting began as the British regulars ascended the first rise of ground. One local historian later wrote the fight was, “…a spirted affair, where one of the Sudbury companies, Captain Cudworth, came up and vigorously attacked the enemy.” As the spirited engagement raged across the high plateau of Brooks Hill the front of the British column soon descended off the eastern rise and into the valley at Elm Brook. After crossing over a small bridge, the British regulars ascended another steep slope to a sharp bend in the Bay Road where multiple companies of Woburn Militia waited to deliver a devastating volley of musketry at close range. Sabin, April 19, 1775; Alfred Sereno Hudson, The History of Sudbury, p. 380. As the Bay Road continued east, it descended Brooks Hill about a mile from Meriam’s Corner. At the bottom of the hill the road crossed “Tanner Brook” at “Lincoln Bridge.” It then turned sharply to the northeast (left) cutting through the Elm Brook Hill. In an area later termed “The Bloody Angle” the road continued northeast for about 300 yards until it made another sharp turn continuing east.

As the British column descended the east side of Brooks Hill and came to “Lincoln Bridge.” At the top of the hill companies of militia from Woburn took position amongst a small orchard. Under the command of Major Loammi Baldwin, the Woburn men brought somewhere between 180 – 200 men into the fight. As the regulars ascended the hill crest the Woburn companies opened a brisk fire then fell back, firing from new positions as opportunity allowed. As the British column plunged ahead through the North turn of the road they were soon met by a heavy fire from their left (North side of the road). Loammi Baldwin later recounted, “We pursued on flanking them… I had several good shots. The enemy left many dead and wounded and a few tired” Edmund Foster of reading also recorded the British suffered “more deadly injury than at any one place from Concord to Charlestown. Eight or more of their number were killed on the spot and no doubt many wounded.” As the British Vanguard pushed past the deadly crossfire at the Northern bend, the British Rear guard staggered across Lincoln Bridge at Elm Brook, pursued by Militia still engaging from the high ground at Brooks Hill. Once the British column had cleared the deadly “S” curve at Elm Brook Hill, they continued onto a relatively flat and open stretch of the Bay Road, past the Mason and Hartwell homes. In this area, the Militia continued engaging the British flanks from positions behind houses and outbuildings with deadly effect. Near the Ephraim and Samuel Hartwell houses militia soldiers concealed behind a barn shot and killed a British grenadier at close quarters, before losing one of their own to British flankers on the other side of the barn. Loses were heavy on both sides in the Hartwell area, Woburn lost Daniel Thompson. Billerica lost Nathaniel Wyman, and the town of Bedford lost its Captain, Jonathan Wilson. Sabin, Douglas “April 19, 1775: A Historiographical Study, Part V, Meriam’s Corner through Lincoln” pg 8-11.:Kehoe, Vincent, “We Were There! April 19th 1775, The British Soldiers” Chelmsford MA 1975. Sometime near 9:00 am a relief column of nearly one thousand British reinforcements left Boston led by Brigadier General Hugh Earl Percy. Hoping to meet Smith’s column quickly, Percy’s relief outpaced an accompanying wagon train loaded with ammunition. As the lightly guarded train passed through Menotomy a group of older men, many of them veterans of the old French Wars, meet at the Cooper Tavern. There they chose David Lamson, a half-indigenous veteran, as their leader and set up an ambush for the supply train. At an opportune moment, Lamson ordered his men to open fire on the horses before calling upon the British drivers to halt and surrender. Instead, they chose to run. In a brief engagement Lamson and his men killed numerous horses and several men. To conceal their attack Lamson’s group rapidly removed the wagons and dead from the road.

Sabin, Douglas “April 19, 1775: A Historiographical Study, Part VII, Meriam’s Corner through Lincoln” pg 7-9. After passing the Smith House, the British remained under constant threat from long-range firing as they made their way east. Minimal written evidence indicates the severity of the fighting between the Captain Smith house and the Nelson farmsteads farther east. In this area, historians hypothesize militia attacks faded to the rear of the column, with provincial forces steadily driving the regulars east. Near the boundary of Lincoln and Lexington, the British advance guard passed the farmsteads of Josiah and Thomas Nelson. In this area, boulder ridden pastures, open farm fields, and apple orchards gave way to a rocky tree covered outcrop. At the base of the hill, a small wooden bridge crossed a stream and created another narrow crossing point. As the British column discovered at the North Bridge, Meriam’s Corner, and Elm Brook Hill, this combination of terrain features spelled certain trouble.

On the long tree covered ridge leading from the rocky hilltop, a company of Militia lay in wait. Captain Parker’s company of Lexington Militia had returned to the battlefield after their disastrous encounter on the Lexington Green earlier that morning. Nathan Munroe, veteran of Parker’s company, remembered fifty years later, “About the middle of the forenoon Captain Parker having collected part of his company, I being with them, determined to meet the regulars on their retreat from Concord. We met the regulars in the bounds of Lincoln. We fired on them and continued so to do until they met their reinforcement in Lexington.” As the British Advanced Guard crossed the small wooden bridge, Parker’s men waited until the regulars arrived within 50 yards before opening fire. Immediately after firing, the Lexington men turned and retired down the egress at their rear and continued, looking for another position to engage the British column again. Constrained by the terrain and necessity to protect the column, the British vanguard and flankers pursued the militia for a short period before returning to the road near the Jacob Whittemore House. Meanwhile, at the rear of the column, near the Josiah Nelson House, the British rearguard and flankers worked to keep the pursuing militia at a distance. In a field just west of the Nelson home, a Lincoln minuteman named William Thorning fired on the British column, before dropping into a drainage ditch to avoid gunfire from flankers sweeping the field. When the Regulars had passed, Thorning rose and found position behind a large boulder where he continued firing. According to local legend, Thorning killed two British soldiers near the Josiah Nelson house. Although the exact number of casualties taken between the Nelson Farms and Parker’s Revenge remains unknown, two British soldiers are buried on a small knoll nearby. Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part V, 25-27.;Deposition of Nathan Monroe, in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775” Vol 2, Part VI: 247.;Frank Coburn, The Battle of April 19, 1775 in Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Arlington, Cambridge, Somerville and Charlestown, Massachusetts (Lexington, Ma: Author, 1912), 103. After pushing through the ambush by Parker’s company and the withering fire from pursuing militia, the British column soon encountered another dramatic terrain obstacle. A few hundred yards beyond the Jacob Whittemore House, is a steep, thickly wooded hill on the north side of the road, known as “The Bluff.” With over a thousand provincial militia quickly closing on the column, the British rear-guard passed the Whittemore house and the Bull Tavern before ascending the sloped sides of the bluff. From this commanding viewpoint covered by trees the Regulars watched Colonial militia advance to the tavern, a building that Reading militia man Rev. Edmund Foster knew as “Benjamin’s Tavern.” The British rear-guard then opened fire from the high ground at the bluff and covered the lead elements of their column now ascending Fiske hill. Rev. Edmund Foster with the Reading militia near the Tavern recalled,

“a man rode up on horse back unarmed. The enemy were then passing round the hill just below the tavern. They had posted a small body of their troops on the north side of the hill, which fired upon us. The horse and his rider fell instantly to the ground; the horse died immediately, but the man received no injury. We were quick at the spot, from which we returned the fire.” Dramatically outnumbered and flanked, the British detachment atop the bluff withdrew. As the regulars descended the rocky hillside into the low area behind, more colonial militia hidden behind trees, rocks and fence rails on Fiske Hill opened fire. Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part VI: 4-5; The “Bloody” Bluff, nps.gov, accessed August 24, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/mima/learn/historyculture/the-bloody-bluff.htm;Rev. Edmund Foster in Ripley, A History of the Fight at Concord, 34. Utilizing scattered tree lots, stone walls, and piles of rail fence, colonial militia staged themselves around the Bay Road. In the distance the long column of weary and battered redcoats struggled toward Lexington; their ammunition nearly exhausted and ranks on the verge of collapse. As they climbed the winding road on Fiske Hill, Reading Minuteman Edmond Foster recalled;

"The enemy were then rising and passing over Fiske's Hill. An officer, mounted on an elegant horse, and with a drawn sword in his hand, was riding backwards and forwards, commanding and urging on the British troops. A number of Americans behind a pile of rails raised their guns and fired with deadly effect. The officer fell, and the horse took fright, leaped the wall, and ran directly towards those who had killed his rider. The enemy discharged their musketry in that direction, but their fire took no effect."- Edmund Foster To avoid complete disaster the Regulars rushed onward, leaving their dead and wounded strewn across the landscape. Near the Fiske House, some individuals stopped either to enter the home or retrieve water from the well. In one intense moment, Acton militiaman James Hayward came face to face with a British Regular exiting the house. According to a local legend recorded fifty years later, the British soldier cried out, “You are a dead man,” and Hayward replied, “and so are you!” Both fired and fell. Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part VI: 4-5; “The ‘Bloody’ Bluff,” nps.gov, accessed August 24, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/mima/learn/historyculture/the-bloody-bluff.htm;Rev. Edmund Foster in Ripley, A History of the Fight at Concord, 32-34.Coburn, Frank Warren, The Battle of April 19, 1775: In Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Arlington, Cambridge, Somerville, And Charlestown, Massachusetts. 2d ed., rev. and with additions. Lexington, Mass.: The Lexington historical society, 1922. Through a tragedy of errors 1st Brigade, under Hugh Earl Percy, did not leave Boston until 9:00 a.m. (Gage issued the order to muster the brigade and march at 4:00 a.m.). By the time they reached Lexington, about half a mile east of the town common, Smith's column was in an almost full headlong retreat. Lt. John Barker, 4th Regiment of Foot recounts...

"The country was an amazing strong one, full of hills, woods, stone walls &c., which the Rebels did not fail to take advantage of, for they were all lined with people who kept an incessant fire upon us, as we did too upon them but not with the same advantage, for they were so concealed there was hardly any seeing them. In this way we marched between 9 and 10 miles, their numbers increasing from all parts while ours was reducing by deaths, wounds and fatigue, and were totally surrounded by such an incessant fire as it's impossible to conceive, our ammunition was likewise near expended. In this critical situation we perceived the 1st Brigade coming to our assistance..." British Ensign Henry De Berniere stated, “within a mile of Lexington, our ammunition began to fail, and the light companies were so fatigued with flanking they were scarce able to act, and a great number of wounded scarce able to get forward, made a great confusion. Col. Smith (our commanding officer) had received a wound through his leg, a number of officers were also wounded, so that we began to run rather than retreat in order.” As the column crested Concord Hill leading into Lexington, the besieged Regulars caught glimpse of salvation on the horizon. A wall of scarlet and red reinforcements. On the ridges east of Lexington, Percy deployed the two 6pdr guns to fire on the pursuing Americans. The first artillery fire of the war sent a shower of splinters flying from the Lexington meeting house and checked the militia advance. With British guns able to strike targets over 1000 yards distance, the militia pulled back to the western edge of Lexington and a lull spread over the battlefield. Over the next half-hour Smith’s forces rallied behind the safety of the 1st Bridge. During the lull, Percy took command of the entire force, and his men burned three structures on the edge of town, sending huge plumes of black smoke into the sky. Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part VI, 6-11; Ensign DeBerniere’s Account Report to Gen. Gage on April 19, 1775 including casualty report , in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” 1: 121;Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part VI: 6-11.; Lexington Back to Boston William Heath, one of five militia generals appointed by the Provincial Congress, and Patriot leader Dr. Joseph Warren, arrived in Lexington and joined the fight. According to General Heath, "Our General, in the morning, proceeded to the Committee of Safety. From the committee, he took a cross road to Watertown, the British being in possession of the Lexington road. At Watertown, finding some militia who had not marched, but allied for orders, he sent them down to Cambridge, with directions to take up the planks, barricade the south end of the bridge, and there to take post; that, in case the British should, on their return, take that road to Boston, their retreat might be impeded. He then pushed to join the militia, taking a cross road toward Lexington, in which he was joined by Dr. Joseph Warren…who kept with him. Our General joined the militia just after Lord Percy had joined the British; and having assisted in forming a regiment which had been broken by the shot from the British field pieces, (for the discharge of these, together with the flames and smoke of several buildings, to which the British, nearly at the same time, had set fire, opened a new and more terrific scene;) and the British having again taken up their retreat, were closely pursued."

Memoirs of Major -General William Heath, August, 1798, 5-9. After a brief rest and time to tend the wounded at Munroe Tavern in Lexington, the British column now under the command of Hugh Earl Percy resumed their march to Boston. With the addition of 1st Brigade, the column now numbered more than 1700 strong. Smith's exhausted soldiers were placed at the head of the column while fresh troops from the brigade formed the rear-guard, the most dangerous post. Lt. Frederick MacKenzie of the 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers wrote in his journal...

"...our Regiment received orders to form the rear guard. We immediately lined the walls and other cover in our front with some marksmen, and retired from the right of companies by files to the high ground a small distance in our rear, where we again formed in line, and remained in that position for near half an hour, during which time the flank companies, and the other regiments of the Brigade began their march in one column on the road towards Cambridge... before the column had advanced a mile on the road, we were fired at from all quarters, but particularly from the houses on the roadside, and the adjacent stone walls..." Account of Lt. Frederick MacKenzie in Kehoe, Vincent, “We Were There! April 19th 1775, The British Soldiers” Chelmsford MA 1975. As Percy’s column entered the town of Menotomy (modern day Arlington) the fighting intensified. Companies from Watertown, Medford, Malden, Dedham, Needham, Lynn, Beverly, Danvers, Roxbury Brookline and Menotomy joined the fight. General Heath continued, “On descending from the high grounds in Menotomy, on to the plain, the fire was brisk. At this instant, a musket-ball came so near to the head of Dr. Warren as to strike the pin out of his ear lock. Soon after the right flank of the British was exposed to the fire of a body of militia which had come in from Roxbury, Brookline, Dorchester &c. For a few minutes the fire was brisk on both sides; and the British had here recourse to their field pieces again; but they were now more familiar than before. Here the militia were so close on the rear of the British, that Dr. Downer, an active and enterprising man, came to single combat with a British soldier, whom he killed with his bayonet.”

Memoirs of Major -General William Heath, August, 1798, 5-9. The fighting along the Battle Road grew more and more grim as the column entered thickly settled areas. One British officer described it as "one continuous village." The fighting was house to house. The home of Jason Russell became a scene of horror as Mr. Russell, 58 years old and lame, refused to be driven from his home. As the British column approached, men from Danvers and Needham barricaded themselves in Russell’s orchard. When a strong contingent of British flankers appeared on the hillside behind the Militia, there was little time to react. Caught between the flankers and the road, the militia fled into Russell’s home, followed by British soldiers. In a desperate fight for life, some militia ran upstairs to the second level and others downstairs into the basement. As the regulars entered the home, they fired their muskets through closed doors and engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the militia they encountered. The regulars brutally killed many of the militia men with bayonets and clubbed muskets. Those men who fled into the basement survived the encounter by firing on British soldiers who attempted to enter. When the Regulars passed, they left a horrific scene of bloodshed including the body of Jason Russell on his own doorstep, bayoneted multiple times. Mrs. Russell later discovered the body of her husband and 11 others in one room of the house with the blood ankle deep.

Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part VIII,12-13. The battle now progressed beyond Alewife Brook into Cambridge. To keep the militia back, the Regulars found recourse in their artillery pieces, dropping trail and firing on the militia incrementally. Unfortunately, according to Lt. William Sutherland, the artillery quickly fell silent for lack of ammunition. As the fighting tightened on the regular’s column, instances of hand-to-hand combat reemerged. In one encounter, Lt. Solomon Bowmen of Menotomy deflected a bayonet thrust from a British soldier and felled the man with a stroke from his musket.

Not far beyond this at a place called Watson’s Corner, a small group of militiamen took cover behind a pile of empty casks in the yard of blacksmith Jacob Watson. Yet again, the militia underestimated the effectiveness of the British flankers. Caught between the flankers and the column Major Isaac Gardner of Brookline was killed along with Moses Richardson, John Hicks, and William Marcy of Cambridge. Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part IX,1-4. As the British column snaked through Cambridge, the severity of their situation sunk in. With ammunition running low and the militia numbers growing by the minute Brigadier General Hugh Earl Percy knew he had to reach safety soon or his column would be cut off. Suspecting that the bridge in Cambridge was held against him (which it was), Percy instead took the road to Charlestown. Near the edge of Cambridge Percy stated a “body” of militia was “drawn up together…just as we turned down towards Charlestown, who dispersed on a cannon shot being fired at them, and came down to attack our right flank in the same straggling manner the rest had done before.” This detour offered Percy the shortest route to safety on the high ground above Charlestown.

Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part IX,5.;Lord Hugh Earl Percy, Report to General Gage, April 20, 1775, in Vincent J-R Kehoe, “We Were There!: April 19, 1775,” At the foot or Prospect Hill militia and British Regulars continued their bloody struggle. With the sun setting, the combatants continued their fight from house to house burning and killing as they passed. Just as the British column approached Winter Hill and the Charlestown neck, a regiment from Salem closed in. Militia General Heath wrote “At this instant an officer on horseback came up from the Medford road, and inquired the circumstances of the enemy, adding that about 700 men were close behind on their way from Salem to join the militia. Had these arrived a few minutes sooner the left flank of the British must have been greatly exposed and suffered considerably; perhaps their retreat would have been cut off.”

Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part IX,7-9. In the darkness, muzzle flashes illuminated the last of the British column slipping across the narrow Charlestown neck to safety. As the militia closed in, General Heath watched the Regulars ascend the high ground above Charlestown turn about and form a strong defensive position. At this point the battle came to a concise close. In a single day of combat, the casualties were staggering. 273 British Soldiers and 95 Militia and civilians were killed, wounded, or missing.

General Heath called a council of officers to debate their next move. A Pickett guard of Militia and British regulars posted at the narrow Charlestown neck and then the evacuation began. The vast majority of Militia marched to Cambridge with orders to “lie on their arms.” At Bunker Hill, fresh British soldiers arrived across the Charles River to relieve the exhausted men of Smith and Percy’s column. Throughout the night all manner of water craft worked to transfer the wounded and exhausted regulars back into the city of Boston. By 4:00 pm on April 20, 1775 the last regular soldiers abandoned Charlestown and returned to Boston. Thus began, and 11 month siege. Sabin, April 19, 1775, Part IX,13. April 19, 1775 was the first battle of the American Revolution. There would be no illusions among the people as to what this war would be like. They saw with their own eyes the horrors of it. Rev. David McClure wrote, "Dreadful were the vestiges of war on the road. I saw several dead bodies, principally British, on & near the road. They were all naked, having been stripped, principally by their own soldiers. They lay on their faces."

As General Gage looked out from Boston he saw entrenchments springing up in the landscape surrounding the city. 4000 minute men and militiamen answered the "Lexington Alarm" and saw combat on the 19th of April. 20,000 overall answered the call. They arrived in the area within the week and immediately established siege operations under the direction of the Provincial Congress and the Committee of Safety. Wagonloads of supplies formed a constant train from the countryside into the Massachusetts Army camps. As militia callouts ended officers recruited soldiers to serve until the end of the year. From a loose collection of minute and militia companies an army took shape, a plan became reality, and the daydream of independency started to grow in the minds of the people. Diary of David McClure, Doctor of Divinity, 1748-1820, Privately Printed, The Knickerbocker Press, New York, 1899, p. 161 |

Last updated: May 17, 2025