Last updated: May 8, 2025

Article

Jazz Arrives in Northeast Ohio

Cleveland Public Library

A Cleveland Press reporter once asked famous jazz pianist Art Tatum, “What is jazz all about?” Tatum replied, “Tell your editor he will never understand it in words.” According to trumpeter and cultural advocate Wynton Marsalis, “Jazz music is freedom of expression with a groove.”

Jazz took root in Northeast Ohio as African Americans moved up from the South in the early 1900s. The Green Book Cleveland project is documenting places of Black recreation and resistance. It is inspired by a Black motorist guidebook that was published from 1936-1966. Green Book research is a priority of the African American Civil Rights Network. Cuyahoga Valley was home to Lake Glen, an African American country club that featured jazz and other forms of entertainment. It was located on the valley’s eastern edge, at 4572 Akron Cleveland Road, and operated from 1950–1964. The nearby Cabin Club (later called the Drift Inn), at 5360 Akron Peninsula Road in Peninsula, offered similar music and entertainment during the same era. This article provides regional context for these two historical sites.

The Origins of Jazz

Scholars disagree on the precise origin of jazz as a word and as a musical movement. Cleveland historian Joe Mosbrook explains that “Jazz, in its many forms, certainly grew out of a wide variety of influences: European church music, African singing, Negro work songs, Negro church music, ragtime music and the blues, but jazz has no clearly defined neat starting point. It has been called a gumbo stirred and seasoned by hundreds of hands. Unfortunately, much of the historical writing on the earliest years of jazz is based on little more than folklore, hearsay and speculation.”

As early as 1812, jazz took shape in New Orleans and surrounding areas in Louisiana. The rhythms and melodies were most significantly shaped by African musical traditions. Both free and enslaved Black community members gathered to jam, dance, and celebrate as a way to counteract systematic oppression. Unlike classical European music, these jazz jam sessions were characterized by what historian Ted Goia calls “the eradication of the division between audience and performer.” Spectators were as much a part of the musical performance as the musicians. Goia says that this mutual experience set the tone for Black music in the chapters of American history that followed, including blues and hip-hop. In many ways, the jam sessions of 1800s New Orleans would define the path of American music as a whole.

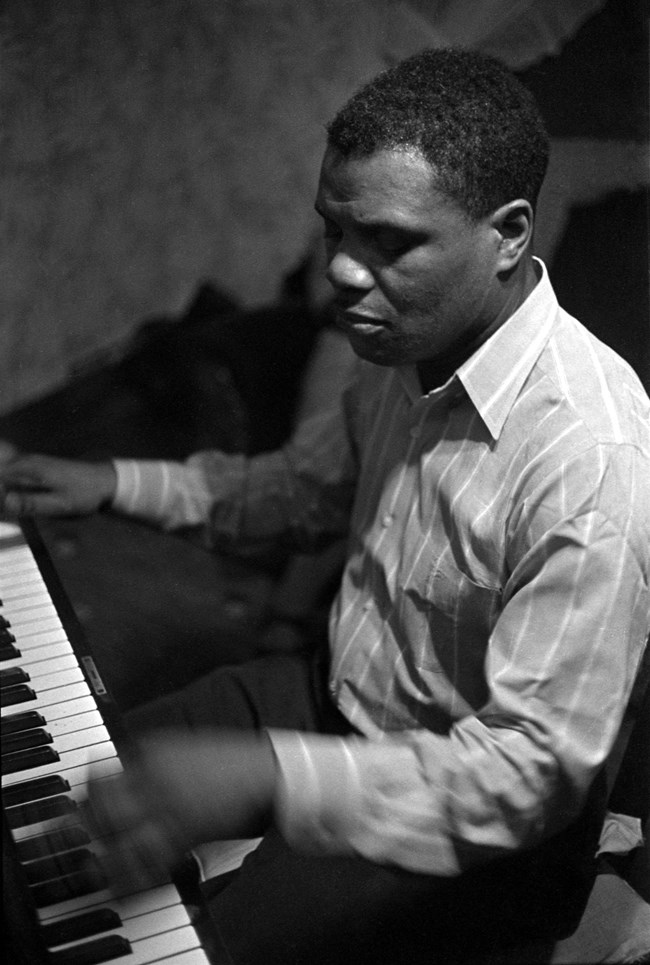

Cleveland Public Library / Jasper Woods Collection

Jazz in Cleveland

“You could park your car on 105th and walk to ten or twelve different clubs featuring live music by Dizzy Gilespie, Miles Davis, Billie Holiday and dozens of others.” —Kenny Davis, renowned Cleveland jazz trumpeter

Jazz and blues traveled northward with emigrants leaving the South during the Great Migration. From 1910–70, an estimated 6 million African Americans moved to northern cities such as Cleveland, Chicago, and Detroit. People moved for different reasons, including seeking better jobs and fleeing southern Jim Crow Laws. Many founded businesses that transformed entertainment and recreation while creating wealth and upward mobility for the Black community. By the 1930s, the United States had about 70,000 Black-owned small businesses. Cleveland’s African American population increased by 307% from 1910–20. Music venues and clubs sprang up in growing communities.

When jazz arrived in Cleveland, the immediate reaction from the mainstream music culture was censorship and skepticism. In 1918, the Cleveland Orchestra conductor Nikolai Sokoloff ordered musicians not to play jazz. In 1925, the City of Cleveland enforced a series of regulations for dance halls which specified that “vulgar noisy jazz music is prohibited . . . Such music almost forces dancers to use jerky half-steps and invites immoral behavior.” Nevertheless, musicians continued to play in Black-owned establishments, practicing both celebration and resiliency.

Well into the 1960s, Cleveland was home to popular jazz venues, including Café Tia Juana and Leo’s Casino. One of the most significant was Val's in the Alley on Cedar Avenue near East 86th Street. Val's was known for performances by nationally acclaimed pianist Art Tatum, a musical prodigy from Toledo, Ohio, who was born with limited vision. Tatum shaped his unique piano style here during night residencies. The Jazz Temple was nearby on Euclid Avenue. Founded in 1962, this coffee jazz house was the brainchild of Black entrepreneur Winston Willis and the legendary trumpeter Miles Davis. Patrons sat at private tables lit by candlelight, sipped coffee, and enjoyed national acts ranging from saxophonist John Coltrane to comedians such as Red Foxx.

Cleveland’s jazz scene declined in the late 1960s as the Black community was subjected to various forms of discrimination, displacement, and changing economic factors. A prime example is East 105th Street. In the 1960s, it was a thriving hub of Black businesses. Many were owned by Winston Willis, one of the biggest employers of African Americans in the Midwest. By the 1980s, Cleveland’s “Second Downtown” was nothing but a memory. Winston Willis and many residents have argued that this erasure was a result of racism and discrimination.

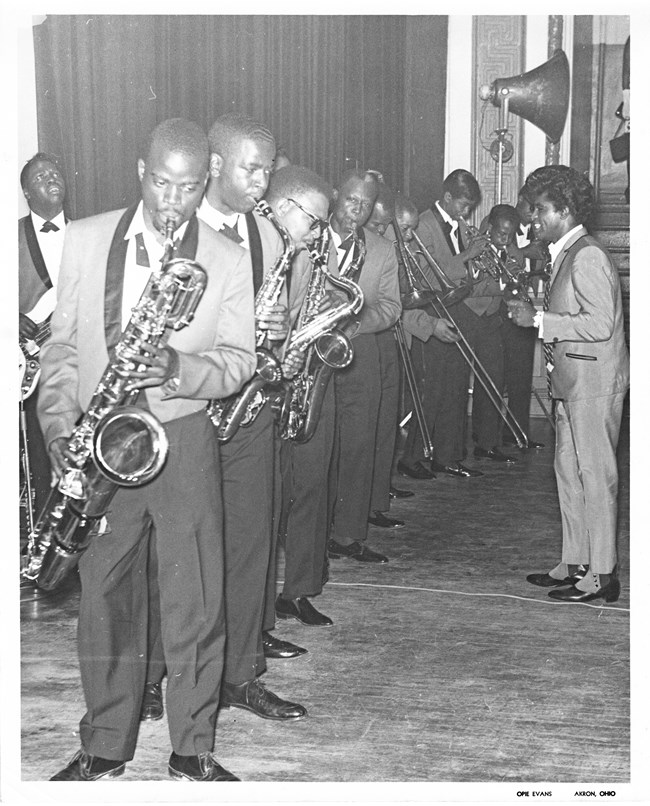

University of Akron, Archival Services / Opie Evans Collection

Jazz in Akron

Between 1930 and 1950, Akron was home to a thriving Black economic district on Howard Street. Like Cleveland’s East 105th Street, Howard Street was a place where African Americans felt ownership of their community. Class mobility and wealth creation were accessible to local residents, in spite of Akron’s active Ku Klux Klan membership which peaked in the 1920s. Hotel Matthews, the Green Turtle Café, and the Cosmopolitan were popular Howard Street venues. According to an oral history account, most concerts would last through the night. Come morning, musicians would gather in private to continue to play together.

Hotel Matthews (1925-1978) was perhaps the most popular hotspot in the city. It offered overnight lodging, a concert venue, a barbershop, and a beauty salon. Proprietor George Washington Mathews started his first boarding house in 1920, becoming the first Black hotel and barbershop owner in Akron. On a national level, it was uncommon for Black entertainers to be able to stay in the same building as their performance. Hotel Matthews was a one-stop shop for all of the stars. The party ended when this section of Howard Street was razed for the Akron Innerbelt project. Freeway construction began in 1970 and stretched into the mid-1980s, never fully completed. Author James Baldwin once provocatively said, “urban renewal means negro removal.” The Black community was displaced with the idea that the area would be revitalized with new development. Howard Street was victim to a nationwide trend of urban renewal destroying Black communities. Today, this story is commemorated by the Hotel Matthews Monument, dedicated in 2016. This project was the life’s work of Akron artist Miller Horns.

In recent years, musician and professor Theron Brown is leading the effort to revive Akron’s rich jazz legacy. His annual Rubber City Jazz and Blues Festival brings together a new generation of musicians to celebrate this American art form. Akron also has several modern jazz-themed businesses near to where the historic clubs stood.

Learn More

Did you know that there are JAZZ Rangers? They perform as part of their duties at New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park. Cuyahoga Valley is connected to this site in two ways. One of our first interpretive rangers, Gayle Hazelwood, served as their superintendent from 1998-2009. Also, two of their singers were evacuated here in 2005 when their park was badly damaged by Hurricane Katrina.

For more background on the local scene, read Cleveland Jazz History by Joe Mosbrook. This book is available in a free digital format on Cleveland State University’s website.

ThirdSpace Action Lab, a Green Book Cleveland partner, is documenting the history of East 105th on their interactive Chocolate City Cleveland map. The project is available as a walking tour app or on their website.

A member of the Green Book Cleveland team from Cleveland State University created this profile of Gay Crosse on Cleveland Historical. Crosse was one of the best Cleveland musicians and a successful businessman in the mid-1900s.

Can you help? E-mail us to share your memories, tips, and family photos with Green Book Cleveland.