Last updated: February 13, 2025

Article

Gayle Hazelwood: A Career of Making National Parks Relevant

The goal was shared among us all: connect people where they are to make the Service and System relevant to them.

Image credit: NPS Collection

National Archives

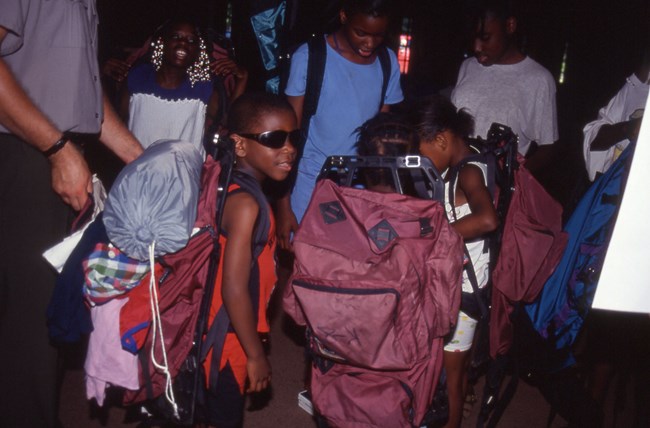

Gayle Hazelwood began her long career with the National Park Service at Cuyahoga Valley and was among our first interpretative rangers. She worked at the young National Recreation Area for about a decade, starting in 1983. Gayle helped pioneer the park’s first Junior Ranger programs. These focused on introducing urban children to outdoor recreational skills, laying the foundation for today’s community engagement programs.

After Cuyahoga Valley, she rose steadily through increasingly prestigious National Park Service positions. She bucked tradition by specializing in small urban parks in the East, rather than large “crown jewels” in the West. A Washington Post article said her “ideal turf involves less buffalo and more asphalt.” Who she is—female, African American, LGB, and 30% American Indian—made her a trailblazer. Becoming the first female superintendent of National Capital Parks—East in 2005 thrust her into the Washington DC spotlight. While there, she received the 2007 Fran P. Mainella Award, named for the first female director of the National Park Service. Gayle capped her career as the national urban program manager.

In 2022, Gayle recorded an oral history with Cuyahoga Valley National Park as part of a Women in Parks project.

An Ohio Childhood

Gayle Hazelwood had an active, outdoor childhood on the edge of Appalachia during the 1960s and 70s. “I was born and raised in Cambridge, Ohio, just 100 miles south of [Cuyahoga Valley National Park]. . . . My parents were the classic loving parents. Worked very hard and allowed us to explore different things.” Her mother was employed by General Electric and her father by the Cambridge Tool and Die Company. “I grew up in the era when your parents kicked you out and said, ‘Come back when the streetlights are on.’ And everybody in the neighborhood knew who you were.” Family was central to her life.

Although Gayle did not spend much time in parks as a youth, she was always engaged in recreation. Her activities included: “Sled riding. Playing with the neighbors. Kickball. Putting tents up over chairs on the patio. Having a campsite. It was those kinds of silly things. But I suppose it did frame me for my appreciation for the outdoors.”

-

Growing Up “I Knew Nothing About the National Park Service”

Gayle Hazelwood describes how her African American family traveled frequently during her childhood but did not visit national parks.

NPS

A Chance Meeting Changed Everything

Gayle has two degrees from Ohio University. “Initially, I thought I wanted to teach physical education.” She had observed a lack of engagement in youth sports when she was at school. While pursuing her master’s in recreation management, she umpired local baseball games.

“I’m the only woman, I’m the only Black woman, and I knew my stuff. The guys wanted to challenge me. I threw one out of the game. It just so happened one of my fellow umpires was sitting in the stands watching. Unbeknownst to me, it was Doug Palmer who worked for the National Park Service . . . If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t be in the NPS.”

Gayle chatted with Doug Palmer between games. He was excited to learn that she had an undergraduate degree in therapeutic recreation and experience with people who have disabilities. He insisted that she get involved with Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area. Her first seasonal job in 1983 was running the Winter Sports Center at Kendall Lake Shelter. The CCC-built facility rented out snowshoes and cross-country skis. Gayle was hired permanently in 1985. This launched her career of more than 30 years with the National Park Service. “I got nothing but support from the staff at the Cuyahoga Valley,” she recalled.

NPS

Starting the Junior Ranger Program

In those early years, Gayle worked closely with coworkers and community partners to create new recreational programs for the young national park. “I had a cadre of volunteers who were just remarkable,” Gayle recalled. “I made really good connections. I met people who were great practitioners of what I wanted to connect people with.”

Together, they established the park’s Junior Ranger Program. The goal was to increase the number of urban and minority youth in outdoor programming. “It became important to recruit kids by going to the different housing authorities and complexes, and literally meeting them where they are,” said Gayle. She taught children outdoor basics in their own community and invited them into the park. “It went from being in houses to actually being out in tents, to having campfires.” For example, she led youth backpacking programs designed to teach wilderness skills.

Gayle developed and led Junior Ranger programs until she left the Cuyahoga Valley in the early 1990s. “It was a nurturing experience.”

-

Connecting People to Parks

Gayle Hazelwood discusses her first job in the National Park Service. She taught outdoor recreational skills to urban groups visiting Cuyahoga Valley.

-

Ranger Gayle, I Remember You!

Gayle Hazelwood reflects on the beginnings of the Junior Ranger Program and its impact.

NPS

Beyond the Cuyahoga Valley

From Ohio, Gayle moved to Georgia and worked for seven years as the chief of interpretation at Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park. “When my career evolved, it really went to the cultural/historic side.” There she opened a new visitor center, featuring the “Courage To Lead” multimedia exhibit, in preparation for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. These Centennial Games introduced a global audience to the history of the American Civil Rights Movement. Atlanta's Olympic slogan was "Come Celebrate Our Dream"—a play on King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

-

Leading at Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site

Gayle Hazelwood reflects on being the Chief of Interpretation at the King site in Atlanta during the 1990s.

As superintendent of New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park from 1998-2009, she helped establish something completely new. “It was a unique experience because it was just such a different type of site for the National Park Service.” She led the park with pride, collaborating with community partners and musicians. “That was memorable. The musicians we met. Getting them to do interpretive programs for visitors and temporary exhibits . . . amazing stuff.”

“Over my career [my identity] became more important because I became the person who could talk to other people of color and make the case for how the National Park Service was a viable option for fun and recreation or a career opportunity.” This was especially true when she oversaw the 14 sites along the Anacostia River that make up National Capitol Parks—East. These include Frederick Douglass National Historic Site and other places which preserve Black contributions to America. Being a high-profile superintendent in Washington DC exposed her to the political side of the National Park Service.

Before retiring in 2016, Gayle was the national urban program manager. In this role, she participated in the collaborative effort to craft the National Park Service’s Urban Agenda during the agency’s 100th anniversary celebration. The goal was to better connect minority communities to urban national parks. Places like Cuyahoga Valley.

Learn More

Explore Black cultural heritage at some of the sites which Gayle Hazelwood helped manage during her career.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park tells the story of the late Civil Rights activist and visionary. Stand where Dr. King stood and visit the church where he preached for equality.

- New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park celebrates jazz as American music with roots in Africa and the Caribbean. Congo Square is where many historians say jazz started.

- Frederick Douglass National Historic Site honors the most famous Black abolitionist of the late 1800s. Douglass’ oratory skills and writings have influenced Civil Rights activists to the present day.

- Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site remembers the founder of The National Council of Negro Women. This site features the meeting place for the council and its members.

- Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site interprets the life of the man who created Black History Month, an American tradition every February.

Tags

- cuyahoga valley national park

- ohio

- midwest

- oral history

- women

- womens history

- women's history

- african american heritage

- african americans

- black history

- nps careers

- national park service careers

- nps employee

- park ranger

- park staff

- careers

- career exploration

- jobs

- what we do

- what do rangers do

- interpretive rangers

- interpretation

- interpreters

- women of the nps

- nps history