Part of a series of articles titled Administrative History of the National Park Service Inventory & Monitoring Division.

Article

I&M Administrative History: Science Struggles

Of the period from 1942 to 1963, National Park Service biologist Lowell Sumner wrote, in his history of the bureau’s biological research and management, “It is unnecessary to recapitulate . . . the frustrations and roadblocks in th[is] period of eclipse for biology.”1 Although historians might wish Sumner had chosen to enumerate some of those frustrations, it’s not difficult, given the major NPS events of those years, to divine his meaning—nor to understand why he may not have wanted to relive them. World War II had brought disinvestment in the parks, as the nation sank its attention, energies, and tax dollars into the war effort. In the war’s aftermath, park visitation immediately resumed at prewar levels and ballooned from there, increasing by 75% from 1946 to 1951.2 Park facilities, many of which hadn’t seen major upgrades since the New Deal era, and hadn’t been sufficiently maintained for the past decade, were rundown and ill-equipped to handle the sheer numbers of people, the vast majority of whom now traveled to the parks in a new way: by automobile. In 1949, NPS Director Newton Drury estimated that $300 million would be needed for satisfactory upgrades. Congress appropriated $14 million for that year’s total NPS budget.3 In his 1953 essay, “Let’s Close the National Parks,” historian Bernard de Voto described conditions worthy of outrage from even the most reluctant patriot, concluding that if Congress wasn’t willing to give the NPS enough money to restore the parks, then the gates should simply be swung shut to protect to save the nation’s treasures from further abuse and deterioration.4

The park service responded with Mission 66, a massive ten-year public works project intended to update and modernize the parks in time for the bureau’s 50th anniversary in 1966. Reportedly the brainchild of new director Conrad Wirth, a landscape architect by training, the overarching purpose of the program was to accommodate the huge increase in auto traffic that had come to define the national park experience. That meant bigger roads, parking lots, and campgrounds; more visitor centers and comfort stations; modernized visitor lodging; more staff; and more staff housing. Day use was emphasized and visitor services were centralized, with some facilities moved out of ecologically sensitive areas. Relative to park resources, Mission 66 was based in the same foundational belief espoused by Mather and Albright in the 1920s: preservation through development. By designing the park experience around the automobile, visitation would be concentrated along roads and facilities in a handful of developed areas, leaving the rest of the parks relatively untouched and thus, protected. At the same time, the National Park System was expanded to include park types geared more toward recreation than preservation, such as national recreational areas and national seashores. All told, about $1 billion was spent to modernize and expand the system.5

What Mission 66 didn’t include was funding for—or much consideration of—science. In the years after the demise of the Wildlife Division and before the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act, the NPS wasn’t required to consider the impacts of its actions on park resources, and often didn’t. Sellars writes that “In the rush of Mission 66, and with nearly three decades having passed since” Fauna No. 1’s recommendation that any development project should be preceded by a biological investigation, “the scientific programs called for in Fauna No. 1 had been rendered virtually impotent.”6 In 1955, as the swiftly planned outlines of Mission 66 became clear, Chief Biologist Victor Cahalane resigned, frustrated that of the $100 million being allocated for the program each year, virtually none was being used to increase funding for biological programs.7 Under a mid-1950s reorganization, most of the bureau’s sparse collection of biologists were reassigned to either the Division of Ranger Activities or the Division of Interpretation. By the start of the 1960s, the Service was down to four field scientists.8

Yet in 1967, at his retirement, Lowell Sumner was hopeful. What had changed?

It is often understood that the fate of science-based management in the NPS began a positive turn with the release of the Leopold and Robbins reports in April and August 1963—the year marking the end of Sumner’s “eclipse.” But an influential catalyst for both reports appeared two years earlier: “Get the Facts, and Put Them to Work: A Comprehensive Natural History Research Program for the National Parks.” This internal report was overseen by Howard Stagner, a geologist, longtime park naturalist, and author of several park guides and handbooks of interpretive techniques. Stagner would eventually rise to Assistant Director, but in 1961, he was Chief of Interpretation in the Natural History Division—and Assistant Chief of the Mission 66 staff. Stagner had conceived “Get the Facts, and Put Them to Work” in response to his disappointment that the Mission 66 team had completely failed to recognize that the NPS needed natural-resources research and management just as much as it needed capital improvements.9

Howard Stagner at Petrified Forest National Park in 1940. NPS/George Grant.

“Get the Facts” began by repeating the concern, from the 1945 report on research in the NPS, that most previous studies had been short-term projects focused on the interests of researchers, rather than management needs. As a result, the findings often ended up sitting on shelves instead of being put to use for the good of the parks. Even research supported by the Service, Stagner argued, had been “directed in piecemeal fashion toward solving immediate problems,” which was not enough to ensure parks were preserved for “future generations,” as required by the Organic Act. A long-term mandate needed a long-term solution. What Stagner proposed was a science program that would move the parks toward “an understanding of “how all elements . . . fit and work together as an ecological whole.”10

“Get the Facts and Put them to Work” asserted that to ensure long-term resource protection, the NPS needed a long-term program that would tackle hot-button issues up front and then keep watch on subsequent conditions. Under this program, staff from each park would work with representatives of universities, research institutions, and other government agencies to draft a list of projects comprising a long-range research plan “based upon the significant natural values of each Park,” and on current and anticipated threats to the park’s “natural economy.” Problems considered to be emergencies would be addressed first, followed by a comprehensive planning process to define which projects would be best able to build on the knowledge already gained. The value of each project would be multiplied as successive studies built on the knowledge it provided. Publication of results would culminate in recommendations for management actions and implementation. By year 5 in each park, it was expected that no monies would need to be devoted to emergency projects—because by that point, “‘crises’ should not develop, because the unfolding comprehensive program will recognize incipient problems and provide the guidance for their solution.” The program, projected to cost $1.3 million, was designed to be phased in over five years, with work beginning first in “Everglades, Isle Royale, Rocky Mountain, Grand Teton, Olympic, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, the Grand Canyon-Zion-Bryce Complex, and perhaps Virgin Islands, Big Bend, Death Valley and Channel Islands,” with additional parks brought in over time.

Recognizing the park service lacked the science capacity to accomplish such a large-scale effort, “Get the Facts” repeatedly specified that most of the actual research would be done by personnel from universities and other organizations. The NPS would coordinate and administer the program, determine what management actions should be taken in response to the results, and implement those actions. In addition, NPS staff would “conduct periodic observations and reappraisals of conditions” after the initial projects were completed, “to provide continuity, to make current assessments of the status of environments, and . . . to anticipate changing and adverse conditions before they become serious.” To this end, the initial research projects were expected to phase into

complimentary [sic] programs of periodic inspection of wildlife, forest and meadow, soils and water, and other ecological situations. . . . The Service must know at all times what is happening, what needs to be corrected, and how to go about it expeditiously. . . . The full value is realized as the knowledge obtained forms the basis for continuous diagnosis of the ecological ‘health’ of Park environments.11

It’s not difficult to discern two crucial elements in the history of NPS inventory and monitoring in Stagner’s proposal: the pre-embryonic outline of vital signs monitoring, with its focus on assessing “ecosystem health” and providing early warning of developing problems; and the differentiation of monitoring from “research.”

“Get the Facts, and Put Them to Work” found an audience in the office of Interior Secretary Stewart Udall. It helped lead to Udall’s appointment of two committees whose findings, released in 1963, would bring significant changes to NPS policy: the Advisory Board on Wildlife Management, chaired by A. Starker Leopold (the “Leopold Report”) and the Advisory Committee to the National Park Service on Research, chaired by William Robbins (the “Robbins Report”).

If the principles underlying Mission 66 had evoked déjà vu for past eras of preservation-through-development, the Leopold Report did little to dispel the sense that history was repeating itself. The report’s “Summary” section echoed the main points of Fauna No. 1 as clearly as if they were still reverberating through a slot canyon where George Wright had shouted them 30 years ago. Passive protection of park plants and wildlife was not enough. Targeted manipulation should be employed to restore the parks to a facsimile of their “primitive” state—defined, as in Fauna No. 1, as being the environment as it existed prior to the arrival of the first European men. Human influence/artificiality on the landscape should be reduced. A strong program of historical and ecological research should precede any management actions. And the most appropriate people to do this work were National Park Service personnel.12

These management recommendations—also like those from Fauna No. 1—were quickly adopted as official NPS policy. But unlike the fast-fading response to Fauna No. 1, NPS adherence to the Leopold Report came to approximate a state of reverence. In fact, in 1975, NPS Chief Scientist Garrett Smathers wrote, “The [Leopold] report had such profound and far-reaching influence on park resources management that it became the ‘Bible’ for development of present policy of managing park ecosystems.” Twenty-two years later, Utah Congressman James Hansen held up a copy of the report during a House hearing and asked NPS Director Roger Kennedy, “is not this still the bible for wildlife management?” Kennedy, after conferring with a colleague, agreed that it was.13

While the Leopold Report gained tremendous public notoriety and had strong, lasting impacts on NPS natural resource management policy and actions, the findings of the Robbins Report, focused on scientific research in the NPS, were less widely publicized—in part by design, as they were more upsetting to NPS leadership.14 The Robbins Committee was asked to evaluate the Service’s research accomplishments and needs in the natural sciences, and submit a report detailing its findings and recommendations. On the subject of accomplishments, the committee acknowledged that quality work had been done by the handful of extremely dedicated employees the bureau had assigned to research over the years—but that their numbers were too few, and their funding inadequate, acerbically pointing out that in 1962, the total amount of money allocated to research in the NPS had amounted to the same cost as one campground restroom.15

In vernacular terms, the committee said the bureau had a long history of being all talk and no action in the pursuit of research: “The status of research in natural history in the national parks has been and is one of many reports, numerous recommendations, vacillations in policy and little action, insofar as actual financial support is concerned. . . . Too few funds have been requested; too few appropriated.”16 Research activities had been so neglected that the committee doubted the NPS even understood how a research program could contribute to problem-solving, observing that until the bureau decided to get serious about supporting research and applying its findings to management, there was little point in continuing to solicit reports and recommendations on the subject. Continuing in the vein of naked honesty and unbounded admonishment, the committee opined, “It is inconceivable . . . that property so unique and valuable as the national parks, used by such a large number of people and regarded internationally as one of the finest examples of our national spirit, should not be provided with sufficient competent research scientists in natural history as elementary insurance for the preservation and best use of parks.”

Quoting directly from Howard Stagner’s report, the committee made the now-familiar observation that research the NPS had undertaken had been disjointed and largely crisis-oriented, designed to address problems of immediate urgency rather than to prevent them from arising in the first place through an approach that took a longer view. Additionally, park managers had failed to implement many of the scientific recommendations they had requested and received. The result of these multiple failures had been direct harm to the resources the NPS was responsible for protecting, as management actions were undertaken without the information necessary to understand their possible ecological consequences. As evidence, the committee cited the destruction of bird habitat to facilitate construction of a motorboat canal at Everglades National Park; severe damage to the root systems of Yosemite’s giant sequoias from roads, vehicles, and trails built too close to the trees; and high costs associated with fixing and relocating roads built on unstable ground near Yellowstone’s thermal features, on clay soils prone to slippage at Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and on permafrost at Mount McKinley National Park. A water project at Mount McKinley had clear-cut a 50-foot swath of vegetation and bench-graded a mile of wilderness hillside; it “proved to be useless and is known locally as the ‘$90,000 icicle.’” At Shenandoah National Park, the unique flora of Big Meadow Swamp had been studied for a quarter-century—until the NPS decided to extend a campground into it, reducing the water level, damaging the plant life, and permanently altering the ecology of the area.

So much for accomplishments. In terms of needs, the Robbins Committee agreed with the Leopold Committee that the NPS needed a research program to support management actions. But it decried the Leopold Committee’s conclusion that the goal of those actions should be to use park landscapes to produce an illusion of the past:

. . . national parks are not pictures on the wall; they are not museum exhibits in glass cases; they are dynamic biological complexes with self-generating changes. To attempt to maintain them in any fixed condition, past, present, or future, would not only be futile but contrary to nature. Each park should be regarded as a system of interrelated plants, animals and habitat (an ecosystem) in which evolutionary processes will occur under such human control and guidance as seems necessary to preserve its unique features.17

Instead of trying to identify a point in time to hearken back to, the Robbins Committee recommended the NPS define the objectives for each park based on its enabling legislation and preserve areas found to approximate a primitive state for research “because of their scientific value as outdoor natural laboratories in which the working of natural laws can be observed to greater advantage than anywhere else and because each such area is a refuge or plant and animal species.” To prevent repeating the economically and ecologically costly mistakes of the past, the committee prescribed the establishment of “a permanent, independent, and identifiable research unit” for the entire National Park System, to “conduct research from long-term considerations, detect problems before they become critical and offer alternate choices of action for their solution.”18

Again following Stagner’s lead, they recommended that a group of scientists be hired to develop a research plan for each park that identified the nature of the problems faced and prioritized a list of projects designed to help solve those problems and anticipate (and prevent) new ones. “One of the first needs,” they wrote, was “a complete inventory of each of the national parks including information on such items as topography, geology, climate, water regime, soil, flora and fauna, land use and archeology, with distribution maps where appropriate.” The committee did not reiterate Stagner’s suggestion that park staff should conduct follow-up activities to assess the state of ecological health, but did repeat George Wright’s recommendation that consultation with the research unit “should precede all decisions” on activities related to “preservation, restoration, development, protection and interpretation, and public use.”19

To support the program, the Robbins Committee recommended a tenfold funding increase, incredulously explaining that whereas the Department of the Interior as a whole had spent 10–12% of its annual appropriations on scientific research, development, and information in 1960–1962, the park service had devoted less than 1% of its annual appropriations to similar activities; approximately one cent per visitor.20

To produce the best, most objective science possible, the committee advocated that scientific personnel “should not be distracted with administrative and operational matters,” and be free to use their professional judgment to decide what kind of studies would best support each park’s mission. At the same time, the science program should be “integrated smoothly into the continuing functions and activities of the Service in such a way as to insure that the results of such a program will be utilized in the decisionmaking process of operational management.”21 Given the bureau’s spotty history of implementing the recommendations of previous scientific efforts, this seems reasonable—and necessary, if real change was to result from the introduction of the research unit.

But in some ways, the idea of an independent research unit, “distinct from administration and the operational management organization,” yet so seamlessly integrated into functional activities that its findings would be routinely used in management operations, represented a bureaucratic unicorn similar to the NPS mandate of simultaneously ensuring preservation and use. To be successful, it seemed, a researcher needed to be both apart from and a part of park operations: insulated from day-to-day concerns about administrative policy and operational activities, yet integrated enough with those concerns to produce recommendations that managers could—and would—implement. With NPS power typically concentrated at the park level, and the proven importance of interpersonal relationships in promoting science-based management, walking the line between insulation and isolation would prove a lasting challenge for NPS scientists.

Despite (or perhaps in line with) the Robbins Committee’s urging that the research unit be distinct yet integrated, the NPS responded to the Leopold and Robbins reports by establishing two new offices dedicated to resource management issues—and promptly sent their staff marching off in different directions. The Division of Natural Science Studies took its cues from the Robbins Report, focusing on research planning. The Division of Resources Studies, assigned to implement the recommendations from the Leopold Report, was dedicated to resource management planning.22 Following Stagner’s model, the Office of Natural Science Studies sent teams of NPS biologists and naturalists, with outside scientists, to survey ecological problems in parks. The teams then created plans outlining the research needed to inventory and evaluate the condition of park resources, and provide the information managers needed to restore and protect that park.23 The first research plans, for Isle Royale, Sequoia-Kings Canyon, and Everglades national parks, were completed in 1966. Nevertheless, the division’s chief, George Sprugel, still felt resistance to the program coming from the director’s office. Sprugel started carrying a letter of resignation around in his pocket, and at some point in 1966, he pulled it out and signed it.24 Under his replacement, Starker Leopold, research plans for Great Smoky Mountains and Haleakala national parks followed, with six plans in place by 1969.25 But by 1975, none of the research plans had been used “specifically as a tool to guide park management.”26

The resource management plans had more success, perhaps because they were tied to the more actionable directives of the Leopold Report, such as removing exotic species and restoring habitat and extirpated species. Once in place, resource management plans had a cadre of employees prepared to carry them out: the “wildlife rangers” who had come to specialize in activities such as fire suppression and control of bears, pests, and non-native species. With their close ties to park superintendents, the wildlife rangers “not only had a substantial role in resource management . . . but also enjoyed much greater bureaucratic influence than did the research scientists,” according to Richard Sellars, who attributed this to the historically close relationship between chief rangers and superintendents and to differences in professional style. More inclined to act on gut instincts than lengthy scientific deliberation, the rangers’ decisionmaking strategies were likely more appealing to superintendents “long accustomed to decisive action.”27 Unfortunately, the research needed for activities called for in resource management plans didn’t always match the research called for in a research plans. Conflicts arose. In some cases, actions associated with resource management plans were carried out without any supporting research, potentially leading to precisely the kinds of situations the Robbins Report was intended to help the Service avoid.28

As Sellars points out, committing to integrate scientific results into management decisions—not to mention increasing science funding to 10% of the bureau’s budget—would have entailed a substantial redistribution of power in the NPS, elevating scientists to unprecedented roles in leadership and decisionmaking and posing “a direct threat to the concept of the Superintendent as the ‘captain of the ship.’” In his response to the Robbins Report, NPS Director Conrad Wirth was quick to clarify that contrary to its specific recommendations, researchers would continue to exercise only advisory authority in park matters. Superintendents, assisted by wildlife rangers, would continue to determine which actions would be taken.29 Under the existing management structure, scientists seemed fated to remain on the outside looking in. Remaining separate from the realm of park operations allowed scientists to preserve their intellectual independence, but meant they would never develop the close relationships with superintendents necessary for inclusion in park decisionmaking.

The bureau’s attitude toward science continued to be characterized by a series of stops, starts, and failures to commit. Not for the first time (nor the last), the NPS, popularly perceived as a leading conservation organization, was out of step with current conservation thinking and practice. As the Service prepared to celebrate its semi-centennial with an orgiastic frenzy of building and development, the Leopold Report urged that “if too many tourists crowd the roadways, then we should ration the tourists rather than expand the roadways.”30 Though Lowell Sumner had admonished NPS officials against the use of DDT as early as 1948, broadscale use of pesticides (including DDT) continued in parks into the mid-1960s (even after the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring), perpetuated by administrators reluctant to abandon past practices. In future years, the NPS would establish a record of poor compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act and publicly oppose the listing of Yellowstone’s grizzly bears under the Endangered Species Act.31

In 1970, the resource- and research-planning functions were combined under the Office of Natural Science Studies, along with the plans each division was responsible for producing. To facilitate the new, combined plans, Science Chief Bob Linn developed a template for prioritizing five years of project, funding, and personnel needs, rooted in a “Resources Basic Inventory” of all known data on park resources. But before he could release it, the NPS reorganized the division again, splitting it into seven regional offices—ostensibly to make them more responsive to park needs.32

The effect was a splintering of any coherent servicewide approach to research planning, and an increase in localized control over funding earmarked for research. Sellars recounts the experience of one biologist, stationed at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, who had received a budget of $5,200 just prior to the reorganization. Soon after, he discovered it had been zeroed out; the regional office had diverted the money elsewhere. By 1973, NPS leadership admitted it was having difficulty figuring out where funds designated for research projects had actually ended up.33 The increase in localized control also meant scientists were increasingly assigned to work on projects of immediate need by individual park managers, returning to more of a brushfire model of crisis-oriented science instead of long-term research projects designed to build upon one another and anticipate future problems.34

Where NPS science programs did make progress, it was often, as with George Wright and the Wildlife Division, the result of the right person being in the right place at the right time—or, in the case of Everglades National Park, the right person from the right place being in the right position of power. Assistant Secretary of the Interior Nathaniel “Nat” Reed, a passionate environmentalist who helped draft the Endangered Species Act of 1973, had spent much of his youth fishing and chasing birds and butterflies on his family’s estate at south Florida’s Jupiter Island, just 40 miles east of Lake Okeechobee.35 By the mid-1960s, the impacts of human development and agriculture had brought the Everglades to the brink of ecological disaster. A century of active efforts to drain the swamp formed by seasonal flooding over the south shore of Lake Okeechobee to the southern tip of Florida had decimated habitat for birds and the area’s other rich fauna; dried out grasses and peat, leading to wildfire in areas where none had been before; and allowed seawater to flow where freshwater should have been. Local hydrology suffered from pollution related to the boom in population and industry. South Florida’s predators, namely alligators and panthers, had been hunted nearly to extinction.36 Then, in 1968, construction began on a gigantic new airport, intended to serve the future needs of a rapidly expanding Miami.

The Everglades Jetport was a futuristic fever dream, fueled by the expansive technological and economic optimism characteristic of the space age. Upon completion, its 39 square miles would have been able to contain O’Hare, JFK, LAX, and SFO airports, side by side.37 Its eight planned runways, each three miles long, and 10–12 terminals were expected to someday serve supersonic jets capable of carrying 1,000 passengers each. A new interstate highway and high-speed monorail would link the airport to both Florida coasts, for fast, easy access to both Miami and Fort Myers. Knowing no one would want to live near the jetport, with its incessant stream of air traffic and supersonic booms, the Dade County Port Authority sought a remote spot for it. They settled on a site about 60 miles west of Miami—and just six miles from Everglades National Park.

The Department of the Interior had concerns. In June 1969, U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist Luna Leopold (brother of Starker) was assigned to evaluate the potential impacts of the project on the Everglades. With jetport construction already underway, Leopold was given just three months to research and write the report, the first environmental impact statement for the state of Florida. With no time to waste, he didn’t mince words. The report’s opening lines read, “Development of the proposed jetport and its attendant facilities will lead to land drainage and development . . . in the Big Cypress Swamp which will inexorably destroy the south Florida ecosystem and thus the Everglades National Park.”38 Report in hand, a broad coalition of hunters, conservationists, citizen activists, and the newly formed Friends of the Everglades—along with Nat Reed, at that time an advisor to Florida governor Claude Kirk—successfully pressured the port authority to stop construction and find another location for the jetport.39 Today, the ill-fated project’s single, 10,500-foot runway serves as an aviation training facility. It is surrounded by Big Cypress National Preserve—established in 1974, during Nat Reed’s tenure as Assistant Secretary of the Interior for the Nixon administration.

The scramble to assemble the science needed to quash the jetport, coupled with the certainty that south Florida’s explosive population growth would guarantee no shortage of similar future proposals, convinced Reed that the Everglades needed a strong, permanent scientific research program.40 At his urging, the South Florida Research Center (SFRC) was also established in 1974.

The center was designed to produce research and management recommendations for four south Florida parks: Everglades National Park, adjacent Big Cypress National Preserve, Biscayne National Monument, and Fort Jefferson National Monument (now Dry Tortugas National Park). Its multi-park scope acknowledged that the entirety of south Florida represented a geographically integrated ecosystem facing shared challenges. The center’s purpose was to “investigate and monitor the natural resources and processes” of that system, and use the knowledge gained to make recommendations for optimal management of the four park units. Unsurprisingly, given the context in which it was created, but unprecedented for the NPS, it was given the task of evaluating the impacts of activities occurring outside park boundaries.41 As Gary Davis, the center’s acting director in 1974–1975, recalled, “Everglades was one of the first parks that really made a serious effort at using science as a guiding principle for its stewardship. [Nat Reed] was convinced that science was the way forward.”42

Assistant Secretary Reed may have been convinced, but according to Davis, “the existing management was not sure that was what they wanted to do. . . . And they resisted all the way.” The South Florida Research Center fell under the administrative purview of the Everglades National Park superintendent, and as “a brand new unit in an old-line organization,” especially one created in response to pressure from outside the NPS hierarchy, it got off to a rocky start.43 Davis, a marine biologist, was the center’s fourth director, the first three having been removed in short order for requesting funding in amounts deemed excessive by those who oversaw the center’s budget and administration. After two years in the position, Davis decided he wanted to spend his time in the field, and went on to lead the center’s marine ecology program.44

Despite its unstable beginnings, the SFRC flourished. Davis recalls that during his time at Everglades, the park’s research program grew from two scientists to 102 in 1980, plus 100 staff dedicated to resource management.45 Marine ecology was one of five programs under the SFRC umbrella, along with hydrology and wildlife, plant, and fire ecology. The center’s first reports focused on wood storks, which had nested by the thousands in the Everglades during the 1930s but been so severely impacted by human alterations to south Florida’s hydrology that none were known to nest successfully from 1967 to 1973.46 By 1982, the center had released 67 reports on topics including crocodiles, colonial nesting birds, water quality, flora, fisheries, mammals, fire history and dynamics, marine animals, butterflies, forests, and off-road vehicle impacts.47 In keeping with the SFRC’s mandate to do both research and “management science,” the reports were numbered with a prefix of T (technical) or M (management), indicating whether a project’s primary purpose was to make relevant contributions to existing knowledge or provide answers to a specific management question.

The impacts of the center’s work were felt almost immediately. In the first M-series report, Davis recommended that all harvest of spiny lobsters in the bay and tidal creeks of Biscayne National Monument be prohibited, based on his findings that the Biscayne Bay lobster fishery had significantly altered the density and age structure of the lobster population. The fishery, Davis found, was removing more than half of the mature lobsters from the bay and tidal creeks each season, and causing growth-slowing injuries to many of the remaining lobsters.48 Establishing a lobster sanctuary would not only help the park service protect the resources in its care, but also benefit the lobster fishery. To determine if the sanctuary was having the desired effect, Davis proposed a program of effectiveness monitoring that would annually assess the abundance, distribution, condition, and size structure of the population.49 Six years later, on July 3, 1984, the State of Florida declared the waters of Biscayne Bay, Card Sound, and Little Card Sound, and their tidal creeks, to be a nursery sanctuary for the spiny lobster.50 Lobstering is still prohibited there.

Davis has observed that eventually, NPS leadership came to see that science could be an important management tool in south Florida.

Further north, another park was experimenting with science-based management. With an origin story and mission similar to those of the South Florida Research Center, the Uplands Field Research Laboratory was established at Great Smoky Mountains National Park in 1975, after a calamitous resource problem convinced senior leaders that science would provide them a solid basis for taking action to protect the park. In 1920, a group of European wild hogs escaped from a hunting enclosure 15 miles from the area that would become the park in 1934. By the 1950s, park staff were finding some areas laid bare from the hogs’ habit of rooting around in the soil, digging up plants and displacing huge pieces of sod.

Erosion caused by rooting of grasslands by wild boars, man posing in background, Gregory Bald, Tennessee, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, 1959. NPS photo.

Erosion caused by rooting of grasslands by wild boars, man posing in background, Gregory Bald, Tennessee, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, 1959. NPS photo.The initial destruction led to subsequent erosion, doing tremendous damage to one of the most biodiverse places on Earth. Despite a direct-reduction program begun in the 1960s, the number of wild hogs in the park had increased from about 500 to nearly 2,000 by the early 1980s.51 Park managers faced other resource challenges, as well—yet like so many other places, had little scientific information on which to base management strategies. Nor, according to former regional biologist Susan Bratton, did they want it.52 But in 1975, the park got a new superintendent, Boyd Evison. Along with strong support from the regional office, Evison’s conviction that better science would lead to better management outcomes brought the Uplands Laboratory, to be led by Bratton, into existence. Its staff performed research and monitoring on a diverse array of resources and threats, including air quality and acid rain, cave fauna, wild boar, black bear, white-tailed deer, aquatic systems, vegetation, fire dynamics, and visitor use impacts.

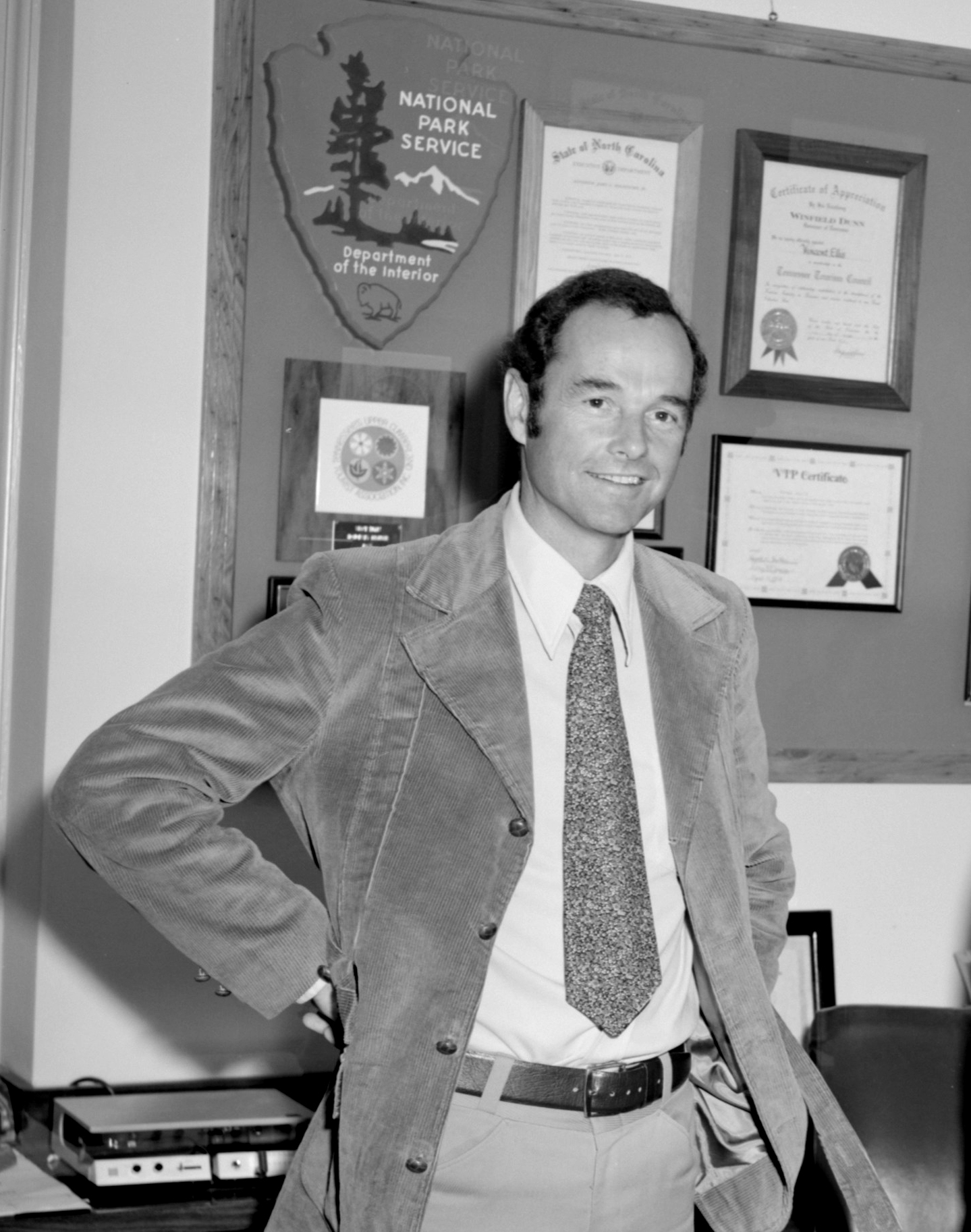

Boyd Evison in 1975. NPS photo.

Boyd Evison in 1975. NPS photo.There were more reasons for hope. Out west, Yellowstone, Grand Teton, Sequoia, and Redwoods national parks also began to assemble personnel to facilitate research and science-based management in the 1970s, albeit at a smaller scale than Everglades and Great Smokies. At the same time, the NPS established a series of partnerships with universities, intended to facilitate park-related research. The University of Washington hosted the first Cooperative Park Studies Unit (CPSU), established in 1970. By 1973, NPS staff were duty-stationed at 18 CPSUs across the nation, assigned to coordinate park-based research by professors and students.53

And in 1975, for the first time, natural resources inventory and monitoring was included on the National Park Service’s list of servicewide management objectives, which stated the bureau’s intention to “clearly identify specific park-related resource inventory and research needs” and “monitor critical resources for change.” The 1978 Management Policies reiterated that “the dynamic nature of plant and animal population [sic], and human influences upon them requires that they be monitored to detect any significant changes.” They also married monitoring to management: “Action will be taken in the case of changes based upon the type and extent of change and the appropriate management policy.”54 But at the servicewide scale, no changes were implemented to support those declarations—likely demonstrating a lack of both the will and the resources needed to translate words into deeds.

In 1980, two events occurred that would help set the course for the future NPS Inventory & Monitoring Division. One was the release of yet another internal report taking the bureau to task for its own lack of access to scientific information in the wake of innumerable threats to the parks. The other was a phone ringing on Gary Davis’s desk.

NEXT CHAPTER >>

<< PREVIOUS CHAPTER

Research and writing by Alice Wondrak Biel, Writer-Editor, National Park Service Inventory & Monitoring Division

1Sumner, “Biological Research and Management in the National Park Service,” 14.

2National Park Service, “Stats Report Viewer,” Annual Summary Report, accessed September 12, 2022, https://irma.nps.gov/STATS/SSRSReports/National%20Reports/Annual%20Summary%20Report%20(1904%20-%20Last%20Calendar%20Year).

3William Everhart, The National Park Service (Westview Press, 1982).

4Bernard de Voto, “Let’s Close the National Parks,” Harper’s, no. October (1953): 49–52.

6Ethan Carr, “‘Mission 66’ (1956–1966): Successes and Failures,” https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/tolur_utgafur/fundir/fila2013/carr_iceland-final.pdf.

6Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 171.

7Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 168.

9Bob Linn, “Editorial,” George Wright Forum 3, no. 4 (Autumn 1983): 1–2.

9Linn, “Editorial,” 1.

10Howard R. Stagner, “Get the Facts, and Put Them to Work: Comprehensive Natural History Research Program for the National Parks” (reprint) George Wright Forum 3, no. 4 (October 1983), 31.

11Stagner, “Get the Facts,” 33.

12A.S. Leopold et al., “Wildlife Management in the National Parks” (Advisory Board on Wildlife Management, March 4, 1963), http://npshistory.com/publications/leopold_report.pdf, 13–14.

13Garrett Smathers, “Historical Overview of Resources Management Planning in the National Park Service” (National Park Service Science Center, 1975), 8; “Science and Resources Management in the National Park Service” (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, February 27, 1997), 61–62, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-105hhrg39698/html/CHRG-105hhrg39698.htm.

14Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 216.

15National Academy of Sciences National Research Council, “A Report by the Advisory Committee to the National Park Service on Research,” August 1, 1963, http://npshistory.com/publications/robbins.pdf, 32.

16National Academy of Sciences National Research Council, “Robbins Report,” 31.

17National Academy of Sciences National Research Council, “Robbins Report,” 21.

18National Academy of Sciences National Research Council, “Robbins Report,” 22, 66.

19National Academy of Sciences National Research Council, “Robbins Report,” 33, 51.

20National Academy of Sciences National Research Council, “Robbins Report,” 56.

21National Academy of Sciences National Research Council, “Robbins Report,” 44.

22Smathers, “Historical Overview of Resources Management Planning,” 10.

23Sumner, “Biological Research and Management in the National Park Service,” 18.

24Marietta Sumner et al., “Remembering Lowell Sumner,” George Wright Forum 6, no. 4 (1990), 37.

25Smathers, “Historical Overview of Resources Management Planning,” 10; Sumner et al., “Remembering Lowell Sumner,” 37.

26Smathers, “Historical Overview of Resources Management Planning in the National Park Service,” 10.

27The rangers’ authority over resource decisions and actions was formalized in 1964, when the ranger division was renamed the Division of Resource Management and Visitor Protection. The division’s new chief, Harthon “Spud” Bill, was concerned that recent trends toward specialization had weakened the status of the ranger division by funneling staff to the interpretive and maintenance divisions, and he was determined to see the ranger division maintain its traditional hold on resource management functions. In a memorandum to Director George Hartzog, Bill argued that as the men “on the ground” most familiar with the parks, it was “wholly logical” for resource management to be a ranger responsibility. Hartzog agreed. Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 222–223.

28Smathers, “Historical Overview of Resources Management Planning,” 9–11.

29Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 216.

30Leopold et al., “Wildlife Management in the National Parks,” 6.

31Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 162, 255, 278–279.

32Smathers, “Historical Overview of Resources Management Planning,” 11.

33Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 230–231.

34Wright, Wildlife Research and Management in the National Parks, 30.

35Richard Sandomir, “Nathaniel Reed, 84, Champion of Floridaʼs Environment, Is Dead,” New York Times, July 13, 2018.

36Russell McLendon, “What Happened to the Everglades?,” Treehugger, May 9, 2018, https://www.treehugger.com/what-happened-to-the-everglades-4863504.

37Ken Kaye, “Grand Vision of Jetport Unrealized,” South Florida Sun Sentinel, July 6, 1997.

38US Department of the Interior, “Environmental Impact of the Big Cypress Swamp Jetport,” September 1969, https://eps.berkeley.edu/people/lunaleopold/(108)environmentalimpactbigcypressswamp.pdf, 1.

39Big Cypress Swamp: The Western Everglades, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxM_ae5gvsQ.

40Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 236. In the 1990s, another airport project was proposed to be built 10 miles from Everglades National Park and two miles from Biscayne National Park. Nat Reed believed US senator Al Gore’s decision to neither support nor condemn the project likely cost Gore at least 10,000 votes in the 2000 presidential election. Michael Grunwald, “To the White House, by Way of the Everglades,” The Washington Post, June 23, 2002.

41National Park Service, “About the SFNRC,” February 25, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/ever/learn/nature/sfnrcaboutus.htm.

42Gary E. Davis, interview by Alice Wondrak Biel and Margaret Beer, January 7, 2020.

43South Florida Research Center, “Annual Research Plan, Fiscal Year 1981” (National Park Service, July 24, 1980), 1.

44Davis, interview by Biel and Beer.

45Davis, interview by Biel and Beer.

46John C. Ogden, James A. Kushlan, and James T. Tilmant, “The Food Habits and Nesting Success of Wood Storks in Everglades National Park 1974,” Natural Resources Report (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1978), abstract.

47South Florida Natural Resources Center, “Technical Reports,” October 3, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/ever/learn/nature/technicalreports.htm.

48Gary Davis, “Management Recommendations for Juvenile Spiny Lobsters, Panulirus Argus in Biscayne National Monument, Florida” (National Park Service, South Florida Research Center, 1978), i, 9–10.

49Monitoring improvement of the fishery was a more complicated matter, given that the lobsters would eventually swim away from Biscayne Bay and enter the larger fishery of the Atlantic coast, but Davis urged the park’s managers not to let that deter them from creating the sanctuary in fulfillment of the NPS mission. Gary Davis, “Management Recommendations for Juvenile Spiny Lobsters,” 11.

50Rule 68B-11.001 Florida Administrative Code § (1984), https://www.flrules.org/gateway/RuleNo.asp?title=THE%20BISCAYNE%20BAY-CARD%20SOUND%20SPINY%20LOBSTER%20SANCTUARY&ID=68B-11.001.

51John D. Peine and Jane Allen Farmer, “Wild Hog Management at Great Smoky Mountains National Park,” in Proceedings of the 14th Vertebrate Pest Conference (University of California at Davis, 1990), 221. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6dq9j2pt.

52Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 237.

53Diane Krahe, “Partners in Stewardship: An Administrative History of the Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit Network,” internal draft of unpublished report (Missoula, MT: University of Montana, April 16, 2012), 11.

54National Park Service, “Management Objectives of the National Park Service,” July 1975, 4; National Park Service, “Management Policies” (US Department of the Interior, 1978), IV-2.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tags

Last updated: September 25, 2023