Part of a series of articles titled Administrative History of the National Park Service Inventory & Monitoring Division.

Article

I&M Administrative History: The Rise of Scientific Management

George Melendez Wright was born in San Francisco in 1904. His father was an American sea captain; his mother came from one of the most prominent families in the city of San Salvador. Orphaned by the age of eight, Wright was raised by a great aunt, Cordelia Wright. Growing up, he spent much of his time hiking around the San Francisco Bay area, developing intellectual and spiritual interests in nature that would come to define his professional life. Described as “highly sociable, keenly perceptive of other people, always generous, and unconcerned with personal status”—qualities that would prove indispensable in later years—Wright graduated high school as president of both his senior class and the school’s Audubon Club.1 After earning a degree in forestry from the University of California at Berkeley in 1925, he went to work as a field assistant for Joseph Grinnell, who had supervised Wright’s minor in vertebrate zoology. Together with Joseph Dixon, an economic mammologist on Grinnell’s staff, Wright spent the summer of 1926 studying the birds and mammals of Mt. McKinley (today’s Denali) National Park, where he discovered the previously unknown nesting location of the surfbird.2

In November 1927, Wright was hired as an assistant field naturalist at Yosemite National Park. In that role, he wrote articles for the Yosemite Nature Notes, taught field classes, and collected field notes using a methodical system pioneered by Grinnell. Over the next two years, his notes largely focused on the birdlife of Yosemite Valley and the status of the park’s deer, bear, and elk. But they also reflected “disgust with a variety of wildlife situations in the national parks.”3 As recounted by Wright’s later colleague, Ben Thompson,

Deer in Yosemite Valley were too abundant and tame. Cougars and other large predators in the Park were believed to be very scarce or nonexistent. Black bears raided campgrounds for food and were fed garbage each evening . . . from the village and lodges. A small remnant of the Tule elk . . . were kept in a paddock . . . as an emergency conservation measure. . . . But the NPS had no full-time staff or program devoted to the necessary field research on which better wildlife conservation . . . could be based.4

Wright decided to change that. In 1929, he received permission from NPS director Horace Albright to conduct a wildlife survey of the national parks—funded not by Congress, but from his own considerable inheritance. Wright hired Joseph Dixon and Ben Thompson, a recent Berkeley graduate and yet another student of Grinnell, as fellow investigators. For the next three years, they conducted the first survey of vertebrates of the national parks on behalf of the NPS. At the time, Albright, wrote, “there is no work going on in the National Park Service today that interests me more than the undertaking of Mr. Wright and his associates.”5

The goal of the Wild Life Survey was not just to create an accounting of which animals were in which parks, but rather to devise science-based solutions to wildlife management problems. In a first for the NPS, the multi-park nature of the study allowed the men to examine issues that were common across multiple parks, and to make recommendations for wildlife policies that could be implemented across the Service. The result of their work, Fauna No. 1, was the first comprehensive statement of wildlife policy by the National Park Service. Following a section that identified and classified the major problems facing park wildlife, Wright and his co-authors discussed the issues faced by different vertebrates in each park of each region, pointing out where there were crossover concerns. Many of the problems were the result of efforts to improve human convenience or otherwise maximize visitor enjoyment as it had been conceived to that point. The authors took an ecological approach, recognizing the systemic interconnectedness between species abundance and distribution, vegetation composition and range condition, and landscape history as it had been impacted by human actions. The study’s regional scale was appropriate, they reasoned, because if common problems could be traced to a common origin, it would be more efficient to address them at a broad scale, rather than by park by park.

The findings and recommendations of Fauna No. 1 were grounded in a single underlying principle: the NPS Organic Act had charged the NPS with “preserving characteristic examples of primitive America,” and by largely limiting its conservation efforts to suppressing poaching, vandalism, predation, and wildfire and manipulating animal populations for human pleasure, the Service was failing to meet that goal. Instead, the authors advocated a program of active intervention aimed at restoring the parks to their “primitive,” or “natural” conditions, defined as their state in “the period between the arrival of the first whites and the entrenchment of civilization in that vicinity.” Once those conditions were restored, the intervention should end; it was important not to overshoot the mark and continue intervening to meet human objectives (as had happened in the past), rather than to simply maintain the “natural” state.6

This represented a sea change in NPS thinking about its own roles and responsibilities. To that point, intervention in natural-resource processes had largely focused on protecting some park resources from others to maximize human enjoyment. Now, the Wild Life Survey was calling for intervention to protect park features from human influence and restore “natural” conditions. The Service’s early efforts to secure its position by convincing the public of the parks’ value had succeeded, they argued; now it was time for the NPS to make preserving park resources, rather than fulfilling public desires, the center of its activities and mission. As Richard Sellars has famously asserted, “The wildlife biologists thus became a minority ‘opposition party’ within the Service, challenging traditional assumptions and practices” and bringing a scientific perspective to the Organic Act’s conservation mandate.7

To that end, Fauna No. 1 outlined many ways existing practices could be modified—most in line with their conclusion that wildlife problems tended to “arise from man’s efforts to force the animal life to . . . fit his concept instead of developing his concept to fit the wild life as it really exists.”8 The best way to modify animal behavior was to modify human behavior. To discourage certain species from using certain areas, they advocated planting vegetation unpalatable to those species. Instead of clearing dead and down trees, parks should leave snags, which provide habitat for some species, where they fell. Not all wildfires should be put out, because they served an ecological purpose. Park zoos should be closed, and bear shows ended, so visitors might experience a natural presentation of wildlife, instead of one shaped by humans for humans.

To date, the biologists argued, people had come to the parks expecting to experience nature as they’d experienced it at home—well-arranged and convenient—and the NPS had obliged. Parks should be different—places where people could instead experience “the new joy of seeking out the wild creatures where they are leading their own fascinating lives.” With this change in human perspective and psychology, many of the parks’ wildlife issues would be resolved.

In direct contrast to the Lane Letter’s instructions that parks be kept as small as administratively possible, Wright and his colleagues advocated enlarging park boundaries to include important winter range for park species, to better protect them from being hunted outside the park. Otherwise, as they observed of Yosemite, “the [park] is like a reservoir with the downhill side wide open.”9

In addition to recommending a complete shift in how the NPS conceived of itself, Fauna No. 1 established, unequivocally, that park management should be informed by science. In response to the dire situation facing the NPS—its wildlife in “immediate danger of losing their original character and composition”—the authors offered a definitive solution: “The logical course is a program of complete investigation, to be followed by appropriate administrative action.”10 Wright and his colleagues advocated that “no management measure or interference with biotic relationships shall be undertaken prior to a properly conducted investigation.” Further, those investigations should be done by the NPS, itself: “Because of the nature of the task, it is inherently an inside job. Constancy to the objective can be made a certainty only by employment of a staff whose members are of the Service, conversant with its policies, and imbued with a devotion to its ideals.”11 This, too, was a departure from policy established in the Lane Letter, which had instructed the NPS to rely on the government’s “scientific bureaus” for solutions to individual resource-related administrative problems. Despite being done in-house, it was important for the investigations to be scientifically objective and independent: “The only reason for attempting this practical type of investigation was to provide park administrators with data which would help them to meet a new and difficult situation. . . . As for individual biases, there were already too many.”12 To ensure no administrator would lack the information needed for management, the authors recommended “that a complete faunal investigation . . . shall be made in each park at the earliest possible date.”13

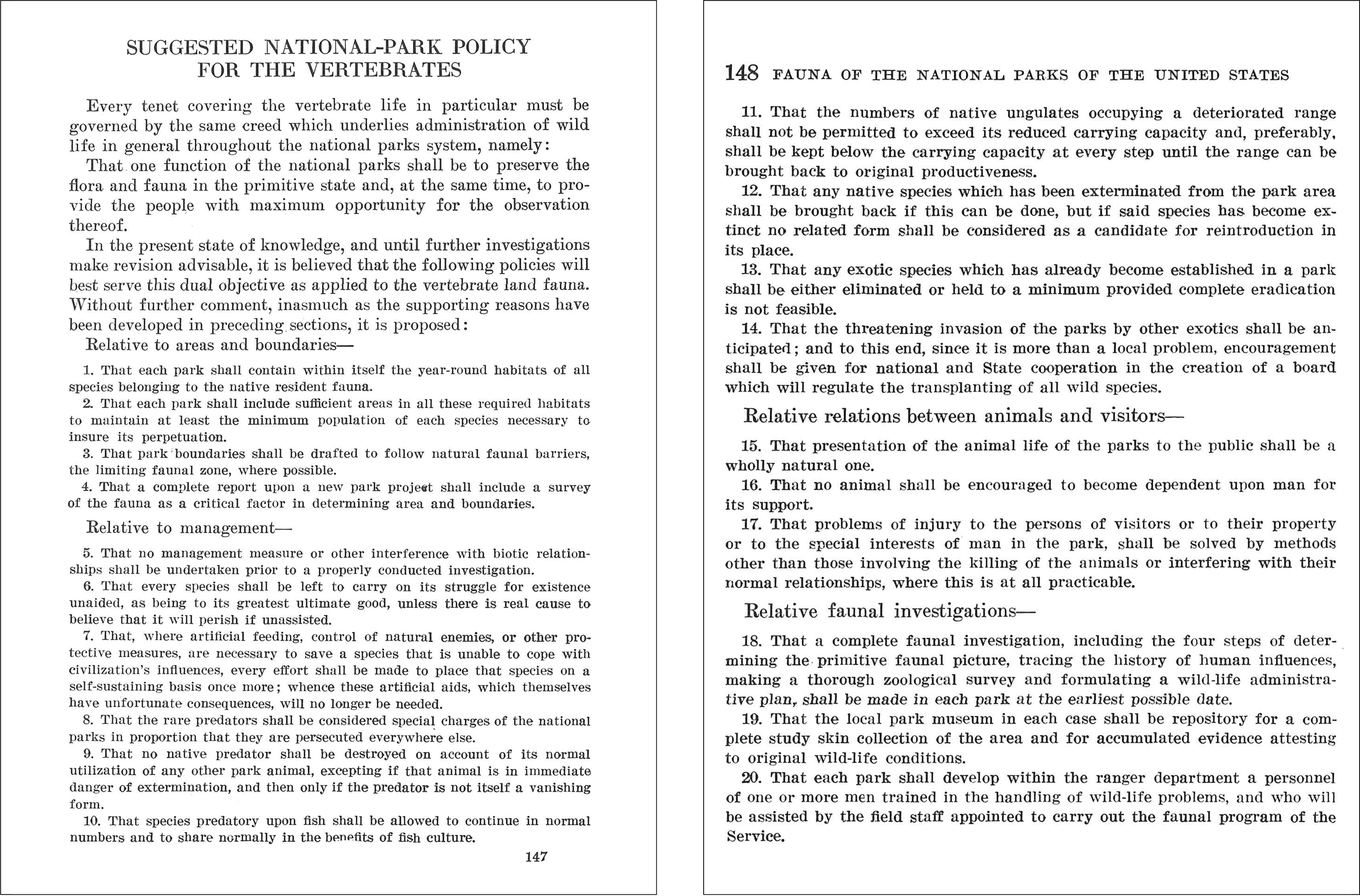

The recommendations made in Fauna No. 1 became official NPS policy in 1934.

At the highest levels of the NPS, the response to the Wild Life Survey, and to Fauna No. 1, was largely positive. The Service had started funding the survey in 1932, when it became the Wildlife Division of the Branch of Research and Education. In 1934, NPS Director Arno Cammerer (Albright having departed in 1933) declared the two pages of recommendations made at the end of Fauna No. 1 (see figure) to be official NPS policy. For the first time in NPS history, park managers were required to use science to inform their decisions and actions.

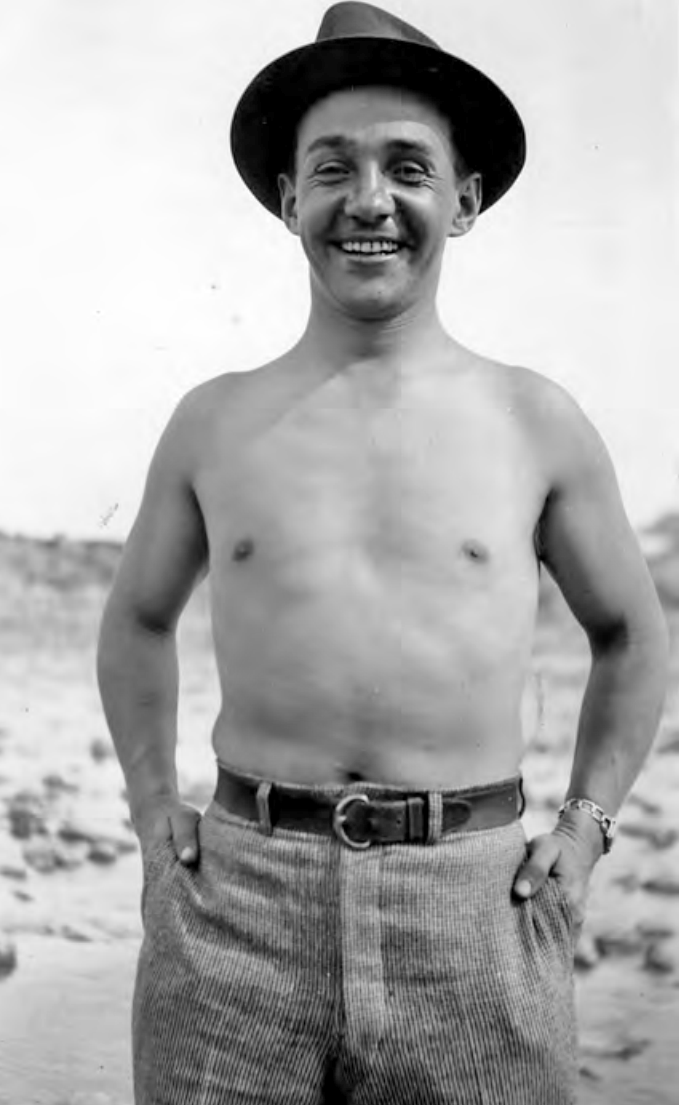

George Wright's “sunny and persuasive personality” contributed to his success in bringing change to the NPS.

George Wright's “sunny and persuasive personality” contributed to his success in bringing change to the NPS.With the charismatic Wright as its chief, the Wildlife Division rose in importance. In 1935, its offices were moved from Berkeley to Washington, DC, closer to the locus of NPS decisionmaking. By that time, its staff of biologists had grown from three to 27, though the vast majority were supported by New Deal funding via the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). The staff split its time between wildlife management and research activities and preparing the biological surveys and review required for all proposed management and development projects.14 Then, tragedy struck, when Wright was killed in a car wreck outside Deming, New Mexico, in February 1936. The subsequent rapid decline of the Wildlife Division, and the role of science in park management, is testament not only to historical realities (the New Deal’s emphasis on development and recreation in the parks; the onset of World War II and its dampening effect on park budgets, staff, and visitation; a post-war focus on building new facilities and welcoming the visiting public back to the parks), but also to the sometimes inescapable importance of having the right person in the right place at the right time. There seems to have been little doubt, among those who knew him, that the success of the Wildlife Division was as much the result of Wright’s willingness to fund the Wild Life Survey, in combination with his “sunny and persuasive personality,” as it was of any genuine administrative appetite for landmark changes in wildlife management.15 As Wildlife Division biologist Lowell Sumner (another former student of Joseph Grinnell, hired into the Wildlife Division in 1935) wrote, “history shows over and over that a brand new unit in an old-line organization has a special need for the soft approach when seeking to win acceptance for new ideas.” Wright had the ability to win people over, set them at ease, and maintain good relations even through disagreement; he “liked people, was outgoing, and generous, and honest, and motivated, and people sensed that. And they reacted to it.”16

At Wright’s death, the Wildlife Division had several eminently qualified scientists on staff, but no one with the personal skills required to carry forward the innovations that had sprouted from the introduction of ecological thinking to park service management. Though the division carried on as best they could, the brief three years between its founding and the death of its chief proved not enough time for the new ideas to fully take hold among NPS leadership, and an “opposing school of thought which, increasingly, was coming to feel that biologists were impractical, were unaware that ‘parks are for people,’ and were a hindrance to large scale plans for park development” began to fill the void created by Wright’s absence.17 Predator-control efforts started to bubble back up at some parks. Staff numbers dwindled in the Wildlife Division, and the group that had broken ground with its servicewide vision was soon reduced to troubleshooting activities and crisis-to-crisis problem-solving. In a final blow, the division’s remaining nine staff members were transferred out of the National Park Service entirely in 1939, becoming the Office of National Park Wildlife for the Bureau of Biological Survey, soon to become the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. At the same time, the word “research” was dropped from the name of the Branch of Research and Education—in part because it had lost its research division, but also because “the climate in Congress had grown increasingly unfavorable to the concept of research.”18 It wouldn’t be the last time the term generated angst for the NPS.

In the void left by the dissolution of the Wildlife Division, the scientific recommendations of Fauna No. 1 were still technically official policy, but there was scarcely anyone left to implement them. Reviewing the many development projects proposed by the CCC had kept the Wildlife Division’s biologists too busy to carry out much of the research recommended in Fauna No. 1. Even more worrisome, the report’s scientific conclusions were proving little match for entrenched attitudes toward predators, bear-feeding, and other traditional ideas and practices. In the late 1930s, pressure built to kill coyotes in Yellowstone and wolves in Mt. McKinley, to “protect” the parks’ antelope and Dall sheep, respectively.

The movement to revive predator control was publicly supported by former NPS director Horace Albright, still highly influential in the conservation community. In a 1937 letter to Director Cammerer, Albright recommended Yellowstone engage in “open war” on coyotes so park staff could see if their stomachs were full of the park’s pronghorn—but then went on to say that coyotes should be killed regardless of the results of any such studies, because even if they were not currently harming the pronghorn population, coyotes were rarely seen by visitors and would always pose a threat to the antelope, “one of the animals most interesting to tourists.”19 Two years later, Albright told Cammerer he saw little value in protecting Mt. McKinley’s wolf population in the “territory of the beautiful Dall sheep;” that in fact, concern for predator conservation “does not or need not fall on the National Park Service at all.”20

In response to the perceived need to kill wild canines to save wild ungulates, the Wildlife Division sent biologist Adolph Murie to study Yellowstone’s coyotes, and then the wolves of Mt. McKinley. His findings, published as Fauna Nos. 4 and 5, “Ecology of the Coyote in the Yellowstone,” and “The Wolves of Mt. McKinley,” were not only sufficient to convince Director Cammerer to stay the course on resisting predator control, but ultimately became classics in the literature on vertebrate ecology.

Murie was frustrated by the “confused thinking” many NPS managers still exhibited toward predators, which NPS biologist David Madsen attributed to “a lack of scientific information,” and a “need for enlightenment” relative to predators.21 Given the continued push for predator control in light of the Wildlife Division’s previous work, official NPS policy, and Albright’s own assertion that he would support its continuation regardless of the results of any further science, it seems unlikely that a “lack of information” was the problem. To assume so, one would have to believe that if only the scientists could accumulate a high-enough pile of facts, then Albright, and those who agreed with him, would change their minds. But for Albright and those in his camp, the need for predator control wasn’t based in facts; it was based in values, and in beliefs about what the National Park Service was for, and what it was supposed to do.

Albright’s ideas about the purpose of the National Park Service were rooted in the concept of aesthetic conservation, which differed from more traditional utilitarian conservation by assigning aesthetic, rather than extractive, value to its resources. In the national parks, for instance, animals were valued for the amount of pleasure they provided to visitors who saw them, rather than for the meat or hides they could provide. Mountains were valued for their beauty, rather than their mining potential. Forests were valued not for timber, but because they were places where people could enjoy the serenity of nature. It stood to reason, then, that the more examples of these resources a park contained, the more valuable it was. This was why the Lane Letter, in its short list of reasons why it might be necessary for a park’s boundaries to be expanded, included the acquisition of “adjacent areas which will complete [a park’s] scenic purposes.” As an example, the letter explained that Yellowstone’s “greatest need” was “an uplift of glacier-bearing peaks,” such as those found in the Teton Mountains, just to the south.

If it sounds strange to think Yellowstone might “need” glacier-bearing peaks, so much as to necessitate a boundary adjustment, it was not so under prevailing ideas about nature in 1918, when the Lane Letter was written. In part, Yellowstone National Park owed its existence to the landscape paintings of Thomas Moran, which had helped convince the US Congress to create the park. Moran was a second-generation artist of the Hudson River School, which frequently depicted untamed, majestic landscapes whose wildness and massive scale helped evoke a sense of the sublime in the viewer—a sense of awe accompanied by a deep sense of fear inspired by magnificent vastness and the clear presence of God. This loose collection of painters held in common the view of America as a new Eden in which humanity had a fresh chance to start over. The paintings are fraught with symbols, and in their effort to imbue them with meaning, the artists often added—or subtracted—visual components to craft an idealized nature that better conformed to the message the artist wanted to convey. In Moran’s 1872 Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, that meant adding tiny humans to the scene, dwarfed by a surrounding landscape that appears ready to swallow them up. Other times, it meant adding scenic elements (like glacier-bearing peaks) to create a composite landscape that contained representational meaning the artist wanted in the scene.22

The lasting influence of this romanticized, aspirational presentation of the western American landscape is evident in the Lane Letter’s implication that a national park might be deficient because it was visually “incomplete.” This definition of deficiency was aesthetic conservation’s equivalent to George Wright’s concerns that a lack of winter range made a park ecologically incomplete; under each view, a park’s resources could not be adequately protected unless it included all the components necessary under its respective paradigm.

Even if their use was non-consumptive, it was still possible for resources to be “wasted” under aesthetic conservation. And the causes of their waste—such as predators and fire—were often the very same entities Wright’s ecologists said needed protection. Little wonder, then, that Albright was unmoved by the facts provided by the Wildlife Division. The scientists insisted that forces Albright knew in his heart to be both worthless and directly destructive to the resources he treasured were actually key to their long-term preservation. It just didn’t make sense, and no amount of scientific facts would make it make sense.

Albright publicly aired his grievances with scientists who sought to shape NPS policy. Of the efforts to end bear-feeding in Yellowstone, Albright wrote,

Not all park visitors can see bears along the roads. This does not disturb the scientific group. They think that if a person wants to see a bear he should go out into the wilds and find one, and then he would see a bear as a child of Nature and be vastly more thrilled and inspired by such a spectacle than to observe one near a highway.23

These comments, made in the journal of a popular conservation organization in 1945, were a direct retort to George Wright’s contention, in Fauna No. 1, that to come upon a bear while “walking along a deep forest trail . . . is a fresh thrill and it brings the realization that the unique charm of the animals in a national park lies in their wildness, not their tameness . . . . It teaches the new joy of seeking out the wild creatures where they are leading their own fascinating lives.” Albright was also reacting to an ongoing study of the feeding habits of Yellowstone’s bears by Olaus Murie (brother of Adolph). Like Wright, Murie advocated for an end to roadside feeding in favor of a more natural presentation: “I think the quality of a national park experience can be improved if we do not try to hand the visitor his recreation on a platter, but let him make at least a little exertion to find it.”24 Yellowstone had ended its grizzly-bear feeding shows by this time—a fact that still irked Albright—but roadside feeding of black bears would continue into the late 1960s, contrary to decades of scientific recommendations and NPS policy, and despite hundreds of injuries and instances of property damage.25

Regardless of whether its leaders followed the recommendations of scientists, the NPS continued, at least nominally, to support the principles outlined in Fauna No. 1, and to call for more science to inform its management decisions. A 1945 internal report, “Research in the National Park System,” reiterated the Service’s commitment to “preserve and restore” park flora and fauna in its “natural and undisturbed state” and provide visitors with opportunities to seek the “higher values” of park plants and animals. “Knowledge of the biology of each park” was “necessary for the proper management of the flora and fauna to insure its perpetuation in a natural state,” and research was required to achieve that knowledge.26 Research was of particular import to planning efforts, both to avoid resource harm during development projects and to ensure those developments would facilitate visitor experience with the protected resources: “The location of buildings and roads must be based on a prior knowledge of the location and relative merits of geological features and biotic communities, first to avoid their destruction and second to make them accessible for visitor enjoyment.”27

To obtain the necessary information, the report recommended a systematized program tailored to the needs of park managers. Studies of “all basic park resources” were to be continued and completed, for use in evaluating development projects and to provide a biological baseline “for the use of future generations”—drawing a straight line between scientific efforts and the NPS’s duty, as defined in the Organic Act, to manage for the long term.

Accompanying these calls for baseline data on park resources was a previously unexpressed recognition that the job wouldn’t be done once the initial assessments were finished. They were the start of a larger, perpetual project:

The research program must procure a constant flow of essential facts relative to the natural features [and] the interrelations of life forms. . . . Investigations of plant assemblages, ecological problems, wildlife diseases, insect infestations, bird migration, and fish culture require a thorough and almost constant surveillance (emphasis added).28

In their use of “constant surveillance” is the germination of the idea that providing scientific information relevant for management purposes required more than just finding out which plants, animals, and problems were found in a park, and identifying the problems they faced. “Nature is not static, but changing constantly,” the report asserted, and to preserve resources in a changing park environment with shifting human demands, one must establish a baseline and then keep track of what happened subsequently. Included in the report’s list of recommendations for 77 park-based wildlife projects were several general “resurveys” intended to bring information previously collected up to date.

“Research in the National Park System” emphasized the importance of collaborating with university scientists and other agencies as a way to acquire research, but acknowledged that such studies would be short-term. Permanent NPS staff would be required to meet long-term needs and ensure the results were carried through to management action:

Men on temporary assignment can produce good results by intensive application to a particular problem for a limited length of time. It is essential, however, that any such program be under the immediate supervision of permanent, trained technicians. Otherwise their efforts will results only in sporadic additions to the total fund of human knowledge which . . . may be published at the end of an investigation [with] the results never reach[ing] application in the field.”29

The authors also recognized that for research results to be useful, their associated data must be properly managed—organized and evaluated “in a manner that will insure its ready adaptation to administrative and interpretive needs.” Though research was needed for management, it should not be influenced by managers, the authors warned: “To make the facts worthwhile, the researcher must be free to discover and report with complete impartiality all facts ascertained in a given situation.” This push and pull between the need for scientists to be independent of management constraints, yet responsive to management needs, would become a defining element of NPS science efforts.

Yet dreams of a well-staffed, well-funded program of National Park Service scientists assigned to provide “a constant flow of essential facts” for management decisions would go unfulfilled for another half-century. NPS Director Newton Drury (1940–1951), who spent much of his directorship fending off water development projects and other proposals to exploit NPS resources for the war effort, was sympathetic to the cause of NPS science but reluctant to request the funding necessary to bring the bureau’s scientific staff back up to prewar levels.30 In 1947, the bureau employed a total of six biologists.31 And in 1951, the arrival of new director Conrad Wirth ushered in an era that would transform the agency—and the parks in its charge—but do little to revive the short-lived practice of science-based management.

NEXT CHAPTER >>

<< PREVIOUS CHAPTER

Research and writing by Alice Wondrak Biel, Writer-Editor, National Park Service Inventory & Monitoring Division

1Jerry Emory and Pamela Wright Lloyd, “George Melendez Wright, 1904–1936: A Voice on the Wing,” George Wright Forum 17, no. 4 (2000): 14–45; Ben H. Thompson, “George M. Wright, 1904–1936,” George Wright Forum 1, no. 1 (1981), 4.

2Thompson, “George M. Wright,” 1.

3Emory and Lloyd, “George Melendez Wright,” 18.

4Thompson, “George M. Wright,” 1.

5Emory and Lloyd, “George Melendez Wright,” 22.

6Wright, Dixon, and Thompson, Fauna No. 1, 10, 21.

7Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 93.

8Wright, Dixon, and Thompson, Fauna No. 1, 54.

9Wright, Dixon, and Thompson, Fauna No. 1, 132.

10Wright, Dixon, and Thompson, Fauna No. 1, 5.

11Wright, Dixon, and Thompson, Fauna No. 1, 5.

12Wright, Dixon, and Thompson, Fauna No. 1, 9.

13Wright, Dixon, and Thompson, Fauna No. 1, 33.

14Sumner, “Biological Research and Management in the National Park Service,” 7.

15Richard West Sellars, “The Significance of George Wright,” The George Wright Forum 17, no. 4 (2000): 46–50; Sumner, “Biological Research and Management in the National Park Service,” 4.

16Emory and Lloyd, “George Melendez Wright,” 40.

17Sumner, “Biological Research and Management in the National Park Service,” 12.

18Sumner, “Biological Research and Management in the National Park Service,” 13.

19Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 121.

20Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 122.

21Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 123.

22John A. Parks, “The Sublime and the Beautiful: Painting the Hudson Valley,” Artists Network, n.d., https://www.artistsnetwork.com/art-techniques/the-sublime-and-the-beautiful-painting-the-hudson-valley/; “The Hudson River School,” The Art Story, n.d., https://www.theartstory.org/movement/hudson-river-school/history-and-concepts/; “Thomas Moran,” The Art Story, n.d., https://www.theartstory.org/artist/moran-thomas/.

23Horace Albright, “New Orders for National Park Bears,” The Backlog: A Bulletin of the Camp Fire Club of America 22, no. 1 (April 1945): 11.

24Biel, Do (Not) Feed the Bears, 48.

25Biel, Do (Not) Feed the Bears, 96.

26National Park Service, “Research in the National Park System, and Its Relation to Private Research and the Work of Research Foundations,” 1945, http://npshistory.com/publications/nps-research-1945.pdf, 10.

27National Park Service, “Research in the National Park System,” 4.

28National Park Service, “Research in the National Park System,” 5.

29National Park Service, “Research in the National Park System,” 12.

30Byron Pearson, “Newton Drury of the National Park Service: A Reappraisal,” Pacific Historical Review 68, no. 3 (August 1999): 397–424.

31Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks, 165.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tags

Last updated: September 25, 2023