Part of a series of articles titled Administrative History of the National Park Service Inventory & Monitoring Division.

Article

I&M Administrative History: Channel Islands

For former Associate Director for Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Mike Soukup, State of the Parks: 1980 marked the end of the NPS’s “naïve era,” in which its leadership believed that defending what lay within park boundaries, using the generalist skills of its ranger force and the intuition of its superintendents, would be enough to protect the parks in its care.1 In 1978, during a period of heightened environmental awareness about the dangers of acid rain, pesticides, pollution, and habitat loss that had led to a bevy of new federal environmental legislation, the National Parks Conservation Association surveyed managers from 203 NPS units about internal and external threats to park resources. The results, published in two issues of the organization’s magazine in 1979, concluded, “Unless all levels of government mount a concerted effort to deal with adjacent land problems in a coordinated manner, the National Park Service mandate . . . will be completely undermined.”2 When news of the NPCA report reached Congress, the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs asked the NPS to provide an overview of potential threats to park resources servicewide. The resulting State of the Parks report explicitly acknowledged the influence of threats originating outside park boundaries—and warned that because of its continuing dearth of science professionals and scientific information about the parks in its care, the NPS was pathetically ill-equipped to do anything about it.

Overseen by NPS Chief Scientist Ted Sudia and Roland Wauer, head of the natural resource management office, State of the Parks was the first comprehensive servicewide attempt to identify and characterize threats endangering park resources. It was based on information provided by park superintendents, resource managers, scientists, and planners, who attributed more than half the reported threats to sources outside park boundaries, including adjacent development projects, air pollution, urban encroachment, roads, and railroads. The most commonly named internal threats were heavy visitor use, utility corridors, vehicle noise, soil erosion, and exotic plants and animals. Since 1963, when the Robbins Report had challenged the NPS to increase its research spending to 10% of the bureau’s overall budget, NPS funding for research had doubled—to 2% of the total budget. Unsurprisingly, 75% of the reported threats were classified as inadequately documented by research. Overall, the report found that park managers lacked “the basic information available for planning and decisionmaking. Very few park units possess the baseline natural and cultural resources information needed to permit identification of incremental changes that may be caused by a threat.”3 The authors made the now-familiar observations that the NPS had invested heavily in construction and maintenance activities while neglecting the pursuit of basic knowledge about park resources, and that where research had been done, it was in response to “only the most visible and severe problems.”

The solution to this information crisis was “a carefully structured and well documented monitoring program,” accompanied by resource management planning to address and mitigate the many threats parks faced. The first step was “to prepare a comprehensive inventory of the important natural and cultural resources of each park;” then, to “conduct comprehensive monitoring programs designed to detect and measure changes both in these resources and in the ecosystem environments within which they exist.” The authors emphasized the importance of improving the bureau’s ability to understand, quantify, and document the impacts of all threats, which would mean significantly increased funding and staff for research and resource management, and professionalizing the work force assigned to those activities. “Simply stated,” the report concluded, “the current levels of science and resource management activities are completely inadequate to cope effectively with the . . . threats and problems . . . discussed in this report. The Park Service, in submitting . . . its findings to the Congress, publicly calls attention to this serious deficiency.”

In January 1981, the NPS sent its remediation plan to Congress. By the end of the calendar year, each park would have a resources management plan (RMP) in place. The RMPs would “(1) include an inventory of park resources and a detailed program for monitoring and managing the resources, (2) specify necessary staff and funding,” and (3) assign project priorities so resources could be directed at the most serious problems.4 They would be updated annually and used in each year’s budget formulation. In addition, 11 initiatives were outlined to improve resource management information, staff training, and scientific research. That same month, Ronald Reagan assumed the presidency, ushering in an administration that NPCA vice president Destry Jarvis would, in 1988, characterize as “the worst in history regarding parks when it comes to the issue of resource protection and conservation.”5 Under Secretary James Watt, the Department of Interior was better known for restricting preservation efforts than for promoting them. But the National Park Service got a strongly conservationist director who would prove a friend to science.

And at a small park once written off as not having much worth preserving, managers were about to create a science program whose example the entire NPS would ultimately come to follow. By the time he placed his call to Gary Davis in 1980, William “Bill” Ehorn had been superintendent of Channel Islands National Monument for six years. Located off the coast of southern California, the Channel Islands are an eight-island archipelago teeming with marine life, endemic island species, and incomparable coastal scenery. It is believed that none of the islands was ever linked to the mainland, but the northern islands (San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, and Anacapa) were likely linked together during a period of low sea level about 17,000 years ago.6 Although the closest channel island is 20 miles from the mainland, the earliest evidence of human habitation dates from about 15,000 years ago. In recent centuries, native Chumash peoples were displaced by the arrival of Spanish soldiers and missionaries, after which the islands experienced a long history of hunting, fishing, maritime traffic, and cattle- and sheep-ranching.

In 1937, the U.S. Bureau of Lighthouses controlled the two smallest islands, Anacapa and Santa Barbara, and leased them for grazing. Deciding the islands were surplus to their needs, the bureau offered them to the National Park Service. When Assistant Regional Director H.C. Bryant took a boat tour to inspect the islands through binoculars, he was largely unimpressed, finding them “barren of . . . rare species, and covered only with grass, annuals, or coast live oak.” Bryant offered a tepid recommendation that some of the vegetation might warrant protection from grazing. He did note that Joseph Grinnell and fellow biologist Loye Miller had both advocated for the transfer. Because the islands were used by sea lions and nesting sea birds, acquiring them would allow the NPS to include a sample of their flora and fauna in the National Park System. Bryant indicated he was still waiting for an opinion from biologist T.D.A. Cockerell.7

Cockerell, who in 1919 had advocated for the natural history survey of Rocky Mountain National Park, was beyond enthusiastic. In addition to his interest in alpine bees, Cockerell was an expert in island biogeography. He was nearing the end of an incredibly prolific career, in which he amassed an astounding 3,904 published papers. The year 1937 found him spending his early retirement in the Channel Islands, collecting specimens and conducting research that would serve as the basis for 16 papers over the next four years. During his time off the California coast, he made significant contributions to knowledge of the islands’ entomology, zoogeography, paleontology, and endemic species; discovered several new species of bees(!); uncovered connections between the zoogeography of island animals and the flow of cool and warm ocean currents; observed that fossilized land snails were found in close stratigraphic association with mammoth fossils; and improved knowledge of island species dispersal and endemism.8

Cockerell sent Bryant a manuscript about San Miguel Island that would eventually be published in Scientific Monthly, told him of his plans to publish a book on the islands, and strongly advised the NPS to take the Bureau of Lighthouses up on its offer. Shortly thereafter, NPS Director Arno Cammerer proposed the establishment of Channel Islands National Monument in a letter to Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, citing “the opportunity to preserve important scientific values needing Government protection” and sharing what he had learned from Cockerell’s work.9 In April 1938, President Franklin Roosevelt established the monument, consisting only of Anacapa and Santa Barbara islands, via presidential proclamation. The next year, the NPS sent Western Region research biologist Lowell Sumner to conduct a resources survey and evaluation of the monument.10

Too small to warrant its own staff, Channel Islands was administered from Sequoia National Park, almost 200 miles and an ecological world away. Its headquarters were moved to Cabrillo National Monument in 1957, a location still distant but at least with a similarly coastal environment. In 1963, after years of urging by Lowell Sumner, the US Navy transferred administration—but not ownership—of nearby San Miguel Island to the NPS. Used as a bombing range from World War II to the early 1970s, San Miguel was also the site of a rookery where thousands of pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) would haul out of the water and breed, creating what Ehorn described as “one of the most magnificent wildlife spectacles I have ever seen in my entire career in the National Park Service.”11 The new agreement authorized the NPS to conduct resource inventory and protection activities on the island, but the pinnipeds were still subject to private capture and other onshore disturbance. In 1977, Ehorn was able to improve protection of those animals through an agreement with the National Marine Fisheries Service and the help of a scientific advisory group that included Starker Leopold, who had witnessed the private captures and become concerned about their effects on the rookery.12

On the horizon, a struggle for protection of a far less charismatic sea inhabitant would redefine both Channel Islands National Monument and the role of science in its management. Based on a 1949 presidential proclamation that declared “the areas within one nautical mile of the shoreline of Anacapa and Santa Barbara Island” to be part of the monument, the NPS had banned commercial harvest of sea kelp from certain areas. In 1950, Lowell Sumner explained the ecological importance of the kelp, and the justification for the harvesting ban:

Kelp beds are very important in quieting the breakers and rough sea surges around the islands. They are a vital shelter for the sea otter and other marine mammals against bad weather and natural enemies, making quiet water along the shoreline where the animals can gather and sun themselves. Marine migratory birds also forage in these kelp beds. In view of the importance of kelp to wildlife, we would be unable to permit its harvesting, but we feel the prohibited area is so small that the effect on the kelp industry will be negligible.13

Representatives from the kelp industry disagreed with Sumner’s last point, and began pressuring the State of California to challenge the ban. In the late 1970s, the state sued the U.S. Government, arguing that under the Submerged Lands Act of 1953, authority over the lands beneath navigable waters rightfully belonged to the states. On May 15, 1978, the US Supreme Court agreed, finding that that the Submerged Lands Act had specifically negated the effects of a 1947 Supreme Court ruling in which the rights claimed by the 1949 proclamation were grounded.14

The next day, as Gary Davis recounts, Superintendent Ehorn sat on a hillside on Santa Barbara Island and watched as a kelp cutter sailed in and then leveled the underwater forest. “And it just broke his heart. And he hadn’t been able to dissuade anybody, and he said, ‘The only way we’re going to [protect this park] is with science. The only way we’re going to do it is to have immutable evidence that everyone agrees to that I can take to a court of law and win this case.’”15 Despite the tiny size of the monument’s staff (about six people), Ehorn was determined to build a science program that could help him protect the marine resources of the Channel Islands in perpetuity.

The first step was to get the monument upgraded to national park status, which would allow for stronger protections than the unit currently enjoyed. Ehorn contacted local Congressman Robert Lagormarsino, who agreed to introduce the necessary legislation.16 They were assisted by Clay Peters, a House staffer who had worked at Lassen Volcanic National Park with both Ehorn and Gary Davis. As it happened, Peters was working on similar legislation for Biscayne National Monument at the time. He contacted Davis, who had been at the South Florida Research Center for about 10 years at that point, to ask what he could put in the bill to help the NPS do a better job of managing resources at Biscayne. Davis didn’t hesitate. Long-term ecological studies were the key, he told Peters, and the new park’s enabling legislation provided an incomparable opportunity to ensure it got them.17 “Put in there something that will give us the rationale to do at least 10 years of study aimed at understanding the long-term dynamics of the system,” Davis urged. Peters was amenable, but with a caveat: “If you call it ‘monitoring’ . . . we can’t get [it] funded,” Davis recalled. “The scientific community won’t support it because it’s not research. It’s not exciting, and the park service doesn’t feel like they need it.”18

Peters had a point. There hadn’t been enough of them, but natural resource inventories had plenty of precedent in the NPS, dating back to academic studies and Bureau of Biological Survey efforts from when the bureau was created. Faunas 1 and 2 were partially devoted to inventory projects. “Get the Facts and Put Them to Work” had complained that most research done in the parks had “been descriptive and of an inventory nature, rather than analytical” in 1961. The Robbins Report found that “a great deal of inventory information” had “been accumulated for some parks.” The Natural Science Research Plans of the 1960s had included projects “needed to adequately inventory and appraise the condition” of natural resources, and the annual report of the NPS chief scientist for 1975 listed no less than 15 natural resource inventory projects underway.19 There was never adequate money for all the inventories parks needed, but in theory it was hard to argue that park managers didn’t need to know what resources were in their care.

More to the point, from Peters’s perspective, inventories were relatively easy to get funded because, much like construction projects, they were singular entities with a clear purpose. Inventories had an identifiable beginning and end, and resulted in a familiar product whose utility was easy to understand. Davis was proposing something completely different. Long-term ecological monitoring took an inventory as its starting point and then revisited the resource over an extended period—for the purpose not of telling a park what it had, but rather how the state of a resource was changing over time. It was much more difficult to convince lawmakers to appropriate funding for a lengthy project with no exciting end product, built around an idea as seemingly mundane as “monitoring” and fundamentally rooted in a commitment to ecological principles that might result in politically problematic results. The South Florida Research Center, for example, had shown that science could be a powerful tool, but there was also concern that it could be limiting if its results failed to support actions managers wanted to take.20

Another limiting factor may have been the idea—introduced in Fauna No. 1, reiterated in the 1945 report on NPS research, and evident in the Service’s implementation of the Leopold Report—that once the NPS had restored a park ecosystem to its “natural” condition, managers should step back and let “Nature” take things from there. If the need for intervention was past once natural conditions were restored, then there would have been little point in investing countless dollars in careful monitoring of what came next.

Davis thought about Peters’s admonition and suggested that instead of “long-term monitoring,” the Biscayne legislation could mandate a series of resource inventories, to be repeated over time, with reporting requirements. Peters, Davis, and Ehorn decided the bill for Channel Islands should include these components, as well.

Ironically, the language calling for long-term studies didn’t make it into the legislation that created Biscayne National Park. But Section 203(a) of the enabling legislation for Channel Islands National Park, created on March 5, 1980, directed the Secretary of the Interior to develop, in cooperation with various public and private entities, “an inventory of all terrestrial and marine species, indicating their population dynamics, and probable trends as to future numbers and welfare;” and “recommendations as to what actions should be considered for adoption to better protect the natural resources of the park.”21 The first report was due to the Secretary by March 5, 1982. Four subsequent biennial updates were required, to cover a total period of ten years.22 For the first time, Congress had mandated that natural resource inventories and monitoring be performed in a national park, and that resulting recommendations be considered for improved park management. Now all the park needed was someone who knew how to put together such a program.

Bill Ehorn knew who he wanted for the job. He had previously tried to recruit Gary Davis to be chief ranger for Channel Islands, but Davis had told him to ask again when he had a scientist position available. That day had finally arrived. Ehorn called to tell him about the position, and in July 1980, Davis packed his bags and headed West.

Channel Islands and Everglades national parks were separated by 2,300 miles of the North American continent and vastly different terrestrial ecosystems. But they shared some familiar challenges, top among them “at the edge of a human tide.” Industries supporting Channel Islands’s 15 million mainland neighbors combined with weather patterns to produce some of the world’s worst air quality in the early 1980s, exceeding federal ozone standards more than 100 days a year. Propelled by the Santa Ana winds, the pollution threatened sensitive plant communities offshore. Urban effluent, offshore oil drilling, and biomass removal from disproportionately large fishery harvesting all put additional stress on island ecosystems.23

Davis had been hired as a research scientist for the NPS Western Region, stationed at Channel Islands National Park and assigned to design the program that would fulfill the new park’s Congressional mandate to produce species inventories, studies of population dynamics and trends, and recommendations for better park protection. Though the park’s enabling legislation didn’t use the language of “monitoring,” Davis’s experience at Everglades National Park, where his mentor, biologist William Robertson Jr., had been carrying on long-term studies of birds, fire, sawgrass, pine forest, and exotic species since the 1950s, had convinced him that’s what Channel Islands needed to achieve the legislation’s intent.24 On his arrival in California, conversations with long-time pinniped researcher Bob DeLong made Davis even more sure he was on the right track.

In November 1980, Davis presented the preliminary design for an inventory and monitoring program at Channel Islands to a gathering of the Western Region research scientists—and was surprised to hear his colleagues reject the monitoring program he’d proposed as not “real research.” Such monitoring had never been done in national parks before, Davis was told, “because it was not possible or feasible, and even if it could be done, many other things were more important for parks to know. Some suggested not enough was even known about park resources to select what to measure and monitor”—precisely the kind of situation the program was intended to rectify.25

Davis took the experience as a data point, rather than a failure. For the program to succeed, it would need to be perceived as both useful for park managers and scientifically valuable: “Turning this situation from rejection to advocacy started with building trust and soliciting help from other park scientists and managers, from academics, and from other agencies and organizations.”26 What ultimately resulted from these partnerships was a plan for the following process: research scientists from inside and outside the NPS would complete a series of short-term (3–5 year) studies to determine which species should be monitored at Channel Islands; identify when, where, and how they would be sampled; explain how the collected data would be managed and reported; and document the monitoring protocols. When its design was complete, the program would be handed over to park resource management staff, who would implement and perform the long-term monitoring as part of regular park operations.27 By teasing out differences between “research” and “monitoring,” this framework helped Davis’s colleagues understand how a monitoring program could, in fact, be considered research. It also helped park managers understand that monitoring would be an integral park function requiring perpetual funding. To paraphrase Davis’s later thoughts:

The tension between research studies and monitoring operations was important to resolve institutionally. Research requires near-constant revision. Each round of hypothesis testing generally requires new funding. Monitoring requires long-term commitments to consistent data collection. Constant funding is needed to assure continuation and consistency. To resolve difficulties with maintaining continuous funding, the National Park Service defined monitoring as an ongoing field-level park operation, just like routine maintenance of park facilities, rather than as centrally directed research.28

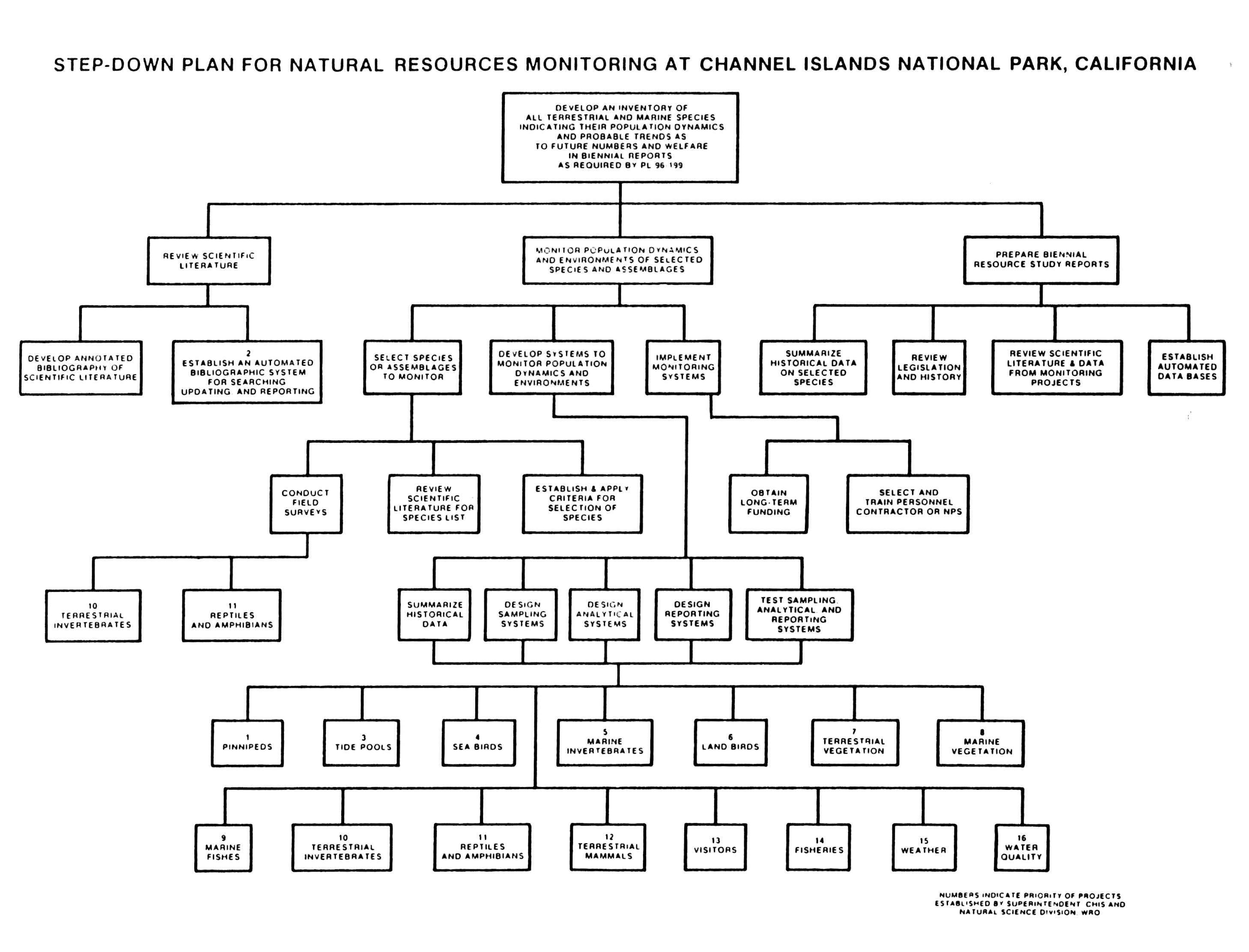

Davis used a step-down diagram to depict the program’s design process (see figure).29 Starting with its mandated goal at the top (taken directly from the park’s enabling legislation), each successive line on the chart indicated the actions necessary to achieve the goal above it. When a line of actions was completed, those actions then became the goals for the actions on the line below.30 The step-down plan culminated in a collection of boxes representing each component of the monitoring program, selected and prioritized by Superintendent Ehorn and the Western Region research scientists and based on a conceptual ecosystem model identifying 15 different system components that could be studied at the population level.31 When those last “steps” representing the different components were reached, the program was ready for operational implementation by park staff.32

The Channel Islands monitoring program developed in accordance with a “stepdown chart” in which each successive line on the chart indicated the actions necessary to achieve the goal above it.

In March 1981, a multi-agency management committee, including representatives from the NPS, NOAA, BLM, and California Fish and Game, met to approve the step-down plan, establish research priorities, and estimate costs. Importantly, they also identified the level of change the program would need to detect to be useful to park managers (a 40% change in mean values), and the level of accuracy the data needed to achieve to be reliable (a=0.05 and b=0.20). To Davis’s recollection, the goal of detecting 40% change “was a pragmatic compromise between cost and risk,” “based largely on concerns about cost and accountability.” Park managers felt they could not afford the expense of detecting smaller (5–10%) changes and could not afford the liability of failing to detect the loss of half the population of a critical resource, such as endemic species.33 The next month, requests for proposals to perform protocol design studies for seabirds, terrestrial vegetation, tide pools, and data management were released.34 Some studies would be completed by Western Region research scientists. Others would be contracted out to various research agencies, academic institutions, and private companies.

Within the broader categories identified from the conceptual model, taxa from extant species lists were selected for sampling as indicator species for each design study. To ensure the indicator taxa represented the overall population dynamics of a given system, subject-matter experts employed a Delphi technique using a fairly standard set of selection criteria: species with special legal status, endemic and alien species, harvested taxa, taxa that dominated or characterized entire communities, exceptionally common taxa, and popularly recognized (“heroic”) species with public support and understanding.35 To monitor kelp forests, for instance, 60 indicator species were chosen, including 15 plants, 33 invertebrates, and 12 types of fish.36 After that, 37 scientists attended a two-day workshop to evaluate and select sampling procedures, applying a set of criteria based on each technique’s capacity for accuracy and precision, resource impacts, cost-effectiveness, data longevity, and complexity.37

Each design study was required to produce a handbook documenting the protocol that would be used to monitor the subject of interest. The handbooks described, in detail, the methods for data collection and analysis. This helped ensure consistent data collection and comparable results over time despite inevitable staff turnover. It was expected the handbooks would be updated over time, to keep pace with technological and methodological innovations.38 Channel Islands eventually developed 14 monitoring protocols, for pinnipeds, seabirds, rocky intertidal communities (tide pools), kelp forests, terrestrial invertebrates, landbirds, terrestrial vegetation, terrestrial mammals, terrestrial reptiles and amphibians, fisheries, visitors, weather, beaches and lagoons, and data management.39 However, due to limited funding, they had to be phased in over time. By 1991, only the first four protocols had been implemented.40 In keeping with the program’s original inspiration, kelp-forest monitoring was the first protocol implemented, in summer 1982.41

Reporting was a crucial—and mandated—component of the Channel Islands monitoring program. Results were published in the “Channel Islands National Park Natural Science Report” series. There were also reports to Congress outlining the management recommendations required by the enabling legislation. As early as 1982, Davis also began describing the program in articles and academic presentations, touting its utility for park management. Program overviews routinely included a paragraph listing examples of how monitoring results had influenced park management decisions, so the program’s impact and value were explicitly clear. From a 1988 report, just six years after the start of monitoring:

The monitoring program is already providing park managers with useful products and providing the scientific community with an ecosystem-wide framework of population information with which to frame research questions and integrate experimental design. Terrestrial vegetation monitoring on Santa Barbara Island documented effectiveness of alien rabbit removal. Monitoring data were used to modify park visitor orientation prior to trips in rocky intertidal zones on Anacapa Island in an attempt to reduce impacts of trampling and rock turning. Kelp forest and intertidal monitoring identified and characterized alarming declines in abalone populations and guided hypothesis formulation and experimental design of specific research to resolve the cause of the observed decline.42

The program’s communications also began to describe its purpose in terms anyone could easily understand: as “vital signs” monitoring of ecosystem health. At lunchtime and on weekends, Davis used to jog with Superintendent Ehorn and the physician for the park’s dive team. As they chatted, Davis—who sometimes struggled to explain the function and utility of the Channel Islands I&M program to non-ecologists—hit upon a medical metaphor he knew would resonate with the two men. Think of an ecosystem, and its components, as a human body, he told them. By taking some key measurements—pulse, temperature, respiration, blood pressure (i.e., the body’s “vital signs”)—a doctor can begin to determine the body’s overall health. Comparing current measurements with established norms and a patient’s long-term history allows the doctor to identify and begin to diagnose problems. Long-term ecological monitoring, Davis explained, worked the same way. By identifying key components and drivers of an ecosystem, biologists can take the same measurements over time to establish baseline norms and assemble a long-term record. Current measurements that misalign with the established range of natural variability provide early warning of potential problems in the broader system.

The metaphor of “ecosystem health” wasn’t entirely novel in the National Park Service. In its 1961 argument for long-term research plans, “Get the Facts, and Put Them to Work” promised their full value would be realized “as the knowledge obtained forms the basis for continuous diagnosis of the ecological ‘health’ of Park environments.”43 Six years later, Lowell Sumner observed, “Just as with warning signals in human health, if critical land resource situations remain undetected . . . they may finally become irreversible. In the last 25 years . . . the ecological health of some parks has come close to this point of no return.”44

But no one employed the metaphor as extensively and consistently as Gary Davis and his colleague, William Halvorson. Their 1988 program overview described Channel Islands I&M as “designed to provide park and sanctuary managers with regular assessments of ecosystem health,” then explained,

Monitoring of resource conditions is analogous to physician conducted physical examinations and diagnostic investigations of patients which are the very basis of modern health maintenance practice. Long years of measuring blood pressure, pulse rate, blood chemistry, temperature, and other vital signs in a wide variety of people under many different conditions have given physicians accurate standards with which to judge a patient's condition and detect illness. The health of park ecosystems can be determined in the same way—by monitoring the systems’ vital signs over a long period of time.45

In a 1989 article for the Natural Areas Journal, Davis expanded the metaphor to explain how all park staff had a role to play in maintaining ecosystem health. Resource managers were family physicians, monitoring ecosystem health with regular checkups, diagnosing illnesses, and prescribing treatments. Park rangers were emergency medical technicians, providing immediate treatments, distributing information, and recommending preventive actions. Research scientists were medical researchers, developing new techniques for assessing health, identifying new diseases, and devising new treatments.46 That same year, the local journal, A'lul'quoy, declared the Channel Islands I&M program “An ‘HMO’ for Channel Islands National Park.”47

The power of the vital-signs metaphor is evident not only in its continued use by the National Park Service today, but also in the legal tussle over it. In the late 1990s, after the NPS had adopted the metaphor for its servicewide I&M program, the bureau was informed that the WorldWatch Institute had trademarked the term and forbidden the NPS from using it. Coinciding as it did with rock musician Prince’s infamous decision to replace his name with a symbol, making him “The Artist Formerly Known as Prince” in prose, the program was jokingly referred to internally as “the program formally known as vital signs” until a resolution was reached.48 But in the mid-1980s, many of Davis’s colleagues in the ecological research community were skeptical that dynamic ecosystems could be characterized as “healthy” or “unhealthy.” Ultimately, Davis was able to convince them that what the metaphor may have lacked in scientific precision, it more than made up for in its ability to communicate the function and importance of the program to lay audiences—including many of the people who would decide whether (or not) to fund the program and make policy decisions based on its results: “I said, if you just give me a break on whether . . . ecosystems ‘have health’ or not, I think that we can make a lot of progress. Well, as it turns out, people are not uncomfortable with that today. The ecological community has certainly come around to agreeing that it’s not a bad concept.”49

Channel Islands National Park was headed toward a place no national park had been before—and few since—functional integration of natural resources inventory and monitoring into park operations. It looked like this:

Resource monitoring was implemented by the entire park staff. Resource managers provide technical expertise and strategic leadership for data collection and report preparation. Rangers provide tactical and logistical leadership. Interpreters describe the importance of the program and present information from monitoring to the public to explain controversial management actions, such as removal of alien species. Maintenance personnel not only provide logistical support, but also give early warnings of impending problems and notification of important phenological events. Administrative staff also provide logistical support and, more important, the glue that binds the team together. Research scientists provide training and continuity to monitoring, and mediate interpretation of monitoring data, trend identification, and hypothesis formulation (emphasis added).50

Asked about this approach in later years, Davis reflected, “That was my hope—that we would get to that point where it was what we do every day. We put the flag up, we take the flag down, and we monitor what’s going on in the park. . . . if we just make that part of what the park does every day, then we’ll win.”51 Looking back in 2004, Davis concluded that the program was still extant because it had “proved to be a cost-effective way to reduce uncertainty and increase success of conservation efforts.” Time and again, the information generated by the program had “significantly reduced uncertainty for management decisions and reduced the costs of resolving serious threats to the park’s ecological integrity.”52 In short, the program had lasted 20 years because it worked.

NEXT CHAPTER >>

<< PREVIOUS CHAPTER

Research and writing by Alice Wondrak Biel, Writer-Editor, National Park Service Inventory & Monitoring Division

1Michael Soukup, “Holding Course,” George Wright Forum 32, no. 3 (2015), 207.

2 Roland H. Wauer, “The Greening of Natural Resources Management,” Trends 19, no. 1 (1982), 3.

3 National Park Service, “State of the Parks -1980: A Report to the Congress,” May 1980, 35.

4 U.S. General Accounting Office, “Parks and Recreation: Limited Progress Made in Documenting and Mitigating Threats to the Parks” (Washington, D.C., February 1987), 2.

5 Maura Dolan, “Reagan Record on Parks Gets Mixed Marks,” Los Angeles Times, June 21, 1988.

6 Gary Davis and William Halvorson, “Inventory and Monitoring of Natural Resources in Channel Islands National Park, California,” October 1988, 4. The southern islands (Santa Barbara, Santa Catalina, San Clemente, and San Nicolas) are not thought to have been linked either to the mainland or each other.

7 Daniel R. Muhs, “T.D.A. Cockerell (1866–1948) of the University of Colorado: His Contributions to the Natural History of the California Islands and the Establishment of Channel Islands National Monument,” Western North American Naturalist 78, no. 3 (2018), 261, https://doi.org/10.3398/064.078.0304.

8 Muhs, “T.D.A. Cockerell of the University of Colorado,” 247.

9 Muhs, “T.D.A. Cockerell of the University of Colorado,” 263.

10 D. S. Livingston, “Island Legacies: A History of the Islands within Channel Islands National Park,” Historic Resource Study (Channel Islands National Park, California, 2016), 34, https://www.nps.gov/chis/learn/historyculture/upload/CHIS-Historic-Resource-Study-FINAL.pdf.

12 Livingston, “Island Legacies: A History of the Islands within Channel Islands National Park,” 102; Interview by Bill Ehorn, 29.

13 Livingston, “Island Legacies: A History of the Islands within Channel Islands National Park,” 36.

14 United States v. California (US Supreme Court May 15, 1978).

15 Davis, interview by Biel and Beer.

16 Interview by Bill Ehorn, 32.

17 Davis had learned the value of long-term monitoring from research scientist William Robertson, Jr., who had been conducting long-term studies of birds, fire, sawgrass, pine forest, and exotic species in the Everglades since the 1950s. Chief among Robertson’s many contributions to NPS science and management was “A Survey of the Effects of Fire in Everglades National Park,” which argued that fire was both natural and necessary for maintaining the South Florida ecosystem, because its fire regime and hydrology were inextricably intertwined. Twenty years after Fauna No. 1, the idea that park systems might need periodic fire to thrive was still not broadly accepted in the NPS. Robertson’s long-term studies helped the bureau begin to change how it thought about fire. Davis, interview by Biel and Beer.

18 Davis, Interview by Gary E. Davis.

19 Stagner, “Get the Facts,” 31; National Academy of Sciences National Research Council, “Robbins Report,” 34; Smathers, “Historical Overview of Resources Management Planning,” 10; National Park Service, “Annual Report of the Chief Scientist of the National Park Service, CY 1975” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, August 1976).

20 Davis, interview by Biel and Beer.

21 96th Congress, “An Act to Establish the Channel Islands National Park, and for Other Purposes,” Pub. L. No. 96–199 (1980).

22 96th Congress. The legislation also specifically included “the rocks, islets, submerged lands, and waters within one nautical mile of each island” as protected areas within park boundaries, negating the jurisdictional issues cited in the Supreme Court’s finding against the park in United States v. California.

23 Davis and Halvorson, “Inventory and Monitoring of Natural Resources in Channel Islands National Park, California,” 6.

24 Chief among Robertson’s many contributions to NPS science and management was “A Survey of the Effects of Fire in Everglades National Park.” Contrary to longtime park service belief and policy, the report argued that fire was both natural and necessary for maintaining the South Florida ecosystem, and demonstrated how the area’s fire regime and hydrology were inextricably intertwined. Proposed in Fauna No. 1 but largely dismissed, the idea that park systems might actually need periodic fire to thrive was still not broadly accepted in the NPS, but Robertson’s long-term studies helped set the stage for later changes to how the bureau thought about fire. Gary E. Davis, “Forrest Gump Lives, or How the George Wright Society Helped Me Learn to Overcome Existential Career Adversity,” George Wright Forum 35, no. 3 (2018), 290.

25 Forrest Gump Lives,” 292.

26 Davis, “Forrest Gump Lives,” 292.

27 Davis, interview by Biel and Beer.

28 Gary E. Davis, “National Park Stewardship and ‘Vital Signs’ Monitoring: A Case Study from Channel Islands National Park, California,” Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 15 (2005), 77.

29 The step-down diagram was a tool used by the US Fish and Wildlife Service to facilitate endangered species recovery. Davis used it extensively in South Florida, then brought it to the Channel Islands. Gary E. Davis, “Visions of Scientific Inventory and Monitoring in the National Park System” (Mediterranean Coast Network meeting, Webinar, January 27, 2021).

30 Davis, "National Park Stewardship and ‘Vital Signs’ Monitoring," 72.

31 Davis and Halvorson, “Inventory and Monitoring of Natural Resources in Channel Islands National Park, California.” 9.

32 The step-down diagram was a simple tool developed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service to facilitate endangered species recovery. Davis had used it during his work in South Florida and brought the concept with him to Channel Islands. Davis, “Visions of Scientific Inventory and Monitoring in the National Park System.”

33 Davis, “National Park Stewardship and ‘Vital Signs’ Monitoring,” 79.

34 Gary Davis, “Channel Islands National Park Vital Signs Monitoring Milestones, 1980–2003,” April 4, 2014.

35 Davis and Halvorson, “Inventory and Monitoring of Natural Resources in Channel Islands National Park, California.” 9.

36 Gary E. Davis, “Kelp Forest Monitoring Program: A Preliminary Report on Biological Sampling Design,” Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit (Channel Islands National Park and Marine Sanctuary: University of California at Davis, May 1985), 8.

37 Davis, "Kelp Forest Monitoring Program," 6.

38 Davis and Halvorson, “Inventory and Monitoring of Natural Resources in Channel Islands National Park, California,” 12.

39 Davis, “National Park Stewardship and ‘Vital Signs’ Monitoring,” 78.

40 Thomas J. Stohlgren and James F. Quinn, “Status of Natural Resources Databases in National Parks: Western Region” (University of California, Davis, California: Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit, May 1991), 4, https://irma.nps.gov/Datastore/DownloadFile/426549.

41 Davis, “Channel Islands National Park Vital Signs Monitoring Milestones, 1980–2003.”

42 Davis and Halvorson, “Inventory and Monitoring of Natural Resources in Channel Islands National Park, California,” 29.

43 Stagner, “Get the Facts,” 33.

44 Sumner, “Biological Research and Management in the National Park Service,” 2.

45 Davis and Halvorson, “Inventory and Monitoring of Natural Resources in Channel Islands National Park, California.” 7.

46 Gary E. Davis, “Design of a Long-Term Ecological Monitoring Program for Channel Islands National Park, California,” Natural Areas Journal 9, no. 2 (1989), 82.

47 Gary Davis and William Halvorson, “An ‘HMO’ for Channel Islands National Park,” A’lul’quoy: A Semiannual Report on Research and Education in the Santa Barbara Channel 2, no. 1 (Spring 1989), 14.

48 Steve Fancy, interview by Alice Wondrak Biel and Margaret Beer, June 12, 2019.

49 Davis, interview by Biel and Beer.

50 Gary Davis, William Halvorson, and William Ehorn, “Science and Management in U.S. National Parks,” The Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 69 (1988): 112–113.

51 Davis, interview by Biel and Beer.

52 Davis, “National Park Stewardship and ‘Vital Signs’ Monitoring,” 7.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tags

Last updated: December 6, 2022