Part of a series of articles titled A Great Inheritance: Examining the Relationship between Abolition and the Women’s Rights Movement.

Article

A Great Inheritance: Prejudice, Racism, and Black Women in Anti-Slavery Societies

This article is part of a series, "A Great Inheritance: Examining the Relationship between Abolition and the Women's Rights Movement" written by Victoria Elliott, a Cultural Resources Diversity Internship Program (CRDIP) intern at Women's Rights National Historical Park.

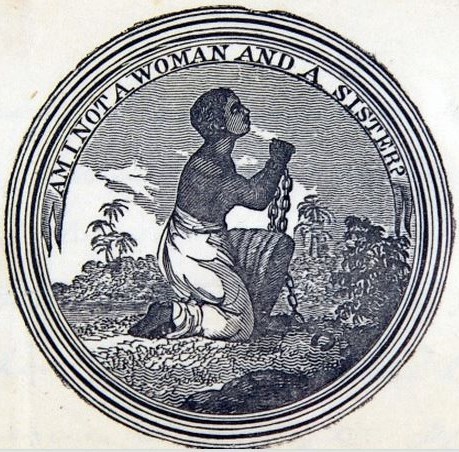

Public domain: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:PFASS_seal.jpg

The establishment of Female Anti-Slavery Societies in the 1830s facilitated the formal beginnings of women’s political participation in the abolitionist movement [12] One women’s antislavery society that formed in the wake of the first American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) convention was the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS).[13] The AASS organized itself as an interracial organization, and PFASS was founded in the same manner. Some African American delegates of PFASS were the Forten Purvises and the Douglass’ women. In addition to being active members of their communities, these women were founding members of PFASS and held several leadership positions within the organization.[14]

Three generations of Forten-Purvis women were members of the PFASS, and several of the Forten-Purvis women were founding members. Charlotte Forten, her three oldest daughters, and her future daughter-in-law Mary Wood all signed the PFASS charter, which was drafted in part by Margaretta Forten. The Forten Purvis women’s anti-slavery activities included hosting anti-slavery meetings, authoring essays and poems for reform newspapers like the Liberator and the Atlantic Monthly, and working as agents of the Underground Railroad. Charlotte Forten and her daughters Harriet, Sarah, and Margaretta were some of the most active reform women of the family. As delegates of PFASS, these women also attended reform and anti-slavery conventions in Philadelphia and New York City [15]

The Douglass’, Grace and Sarah, were responsible for creating several reform and literary societies for African American women. Grace Douglass was a founding member of PFASS and served as a PFASS delegate. Her daughter, Sarah, was intensely involved with the society, acting as a member on the board of managers and fund-raising fair committees. Sarah Douglass also held the positions of librarian and recording secretary for PFASS. In addition to her activities in PFASS, Sarah Douglass also worked to create opportunities for the education of black children as coordinator of a black Philadelphia primary school.[16]

Wealthy and educated, these families are examples of prominent and elite African Americans in Philadelphia society.[17] Their experiences, both socially and within Female Anti-Slavery Societies, were the exception rather than the rule for free African American women in the 19th century. The middle-class status of these women afforded them opportunities otherwise withheld from African American women. However, these advantages could not wholly shield the Douglass’ and the Forten-Purvises from racial prejudice. Sarah Forten herself experienced racial discrimination, though recognized that her family’s position protected her from such experiences: “We are not disturbed in our social relations- we never travel far from home and seldom got to public places unless quite sure that admission is free to all- therefore, we meet none of these mortifications which might otherwise ensue."[18] Charlotte Forten's granddaughter also lamented over the racial prejudice she experienced, even among white allies:

"But to those who experience them [racist snubs], these apparent trifles are most wearing and discouraging; even to the child's mind they reveal volumes of deceit and heartlessness, and early teach a lesson of suspicion and distrust. Oh! It is hard to go through life meeting contempt with contempt, hatred with hatred, fearing with good reason to love and trust hardly any one whose skin is white, - however loveable, attractive and congenial in seeming."[19]

Racism was experienced by many African Americans within the anti-slavery movement in the North. For example, when African American women began to attend the Massachusetts Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1835, the group nearly disbanded over the decision to interracialize the society.[20] Similarly, the Western New York Female Anti-Slavery Society divided when African American women were admitted as members.[21] Rosalyn Terborg-Penn cites such instances of racism against African American women as impetus for the establishment of racially separate societies instead of racially integrated anti slavery societies.[22]

In addition to experiencing racism and prejudice within the anti-slavery movement, African American women were subject to the pressures of representing the “ideal” free African American woman. African American women were expected to maintain their homes, be domestic angels, devote themselves to campaigns to free and advance African Americans, and mirror the white middle class. It was believed that by emulating white middle-class values, African Americans would demonstrate their equality to white Americans, thus eliminating racial prejudices. White abolitionists instructed free African Americans to adhere to white middle-class standards and values, advising them to educate themselves, conduct themselves measuredly and industriously, as this was necessary for African Americans to “rise” to the standing of their white counterparts. These instructions indicate the belief in the inferiority of free African Americans to white Americans.[23]

In the 1830s, such impositions on freed African Americans by abolitionists created what Dr. Lawrence J. Friedman calls “emotional distance” between Euro Americans and Northern free blacks. White abolitionists held paternalist attitudes towards free and enslaved African Americans.[24] The relationship established by most white abolitionists towards African Americans was comparable to that of the missionary and the missionary’s intended convert. Abolitionists posed themselves in positions to uplift those beings who were “less than” their white, middle-class selves. However, such prejudice was not entirely unchecked or unrecognized by abolitionists. Several individuals, both black and white, wrote and spoke against racism publicly and privately. Due to their importance in both the abolitionist and women’s rights movements and their renunciations of racism, Maria W. Stewart, the Grimké sisters. and Lucretia Mott are of primary interest and have been selected as examples.

Maria W. Stewart

Maria W. Stewart was the first recorded American woman to speak publicly. She was born a free African American woman in New England and gave at least four public lectures between 1832 and 1833.[25] Her speeches called attention to issues faced by Northern free African Americans. On September 21st, 1832 at Franklin Hall, Boston, she lectured, “Tell us no more of southern slavery; for with few exceptions, although I may be very erroneous in my opinion, yet I consider our condition [the condition of free African Americans in the North] but little better than that.”[26] In the same speech she drew particular focus to the situation and prejudices against free African American women:

I have asked several individuals of my sex, who transact business for themselves, if providing our girls were to give them the most satisfactory references, they would not be willing to grant them an equal opportunity with others? Their reply has been–for their own part, they had no objection; but as it was not the custom, were they to take them into their employ, they would be in danger of losing the public patronage. And such is the powerful force of prejudice. Let our girls possess what amiable qualities of soul they may; let their characters be fair and spotless as innocence itself; let their natural taste and ingenuity be what they may; it is impossible for scarce an individual of them to rise above the condition of servants.[27]

Widowed three years into her marriage to James W. Stewart, Maria Stewart was “cheated out of her husband’s inheritance by unscrupulous lawyers and left impoverished,” which led to her career as an author and public speaker.[28] However, her engagement in this career was cut short. Tired of public ridicule and abuse, Maria Stewart gave her farewell address in September of 1833 and moved north to New York.[29]

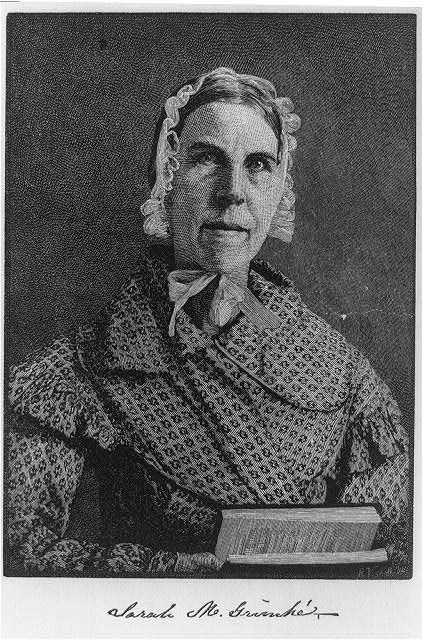

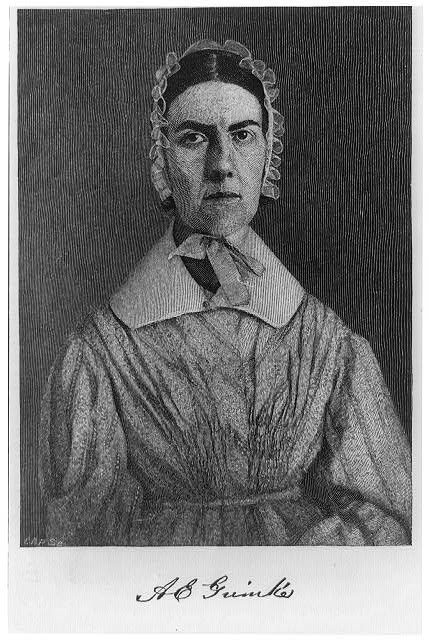

Sarah and Angelica Grimké

Sarah and Angelica Grimké, likewise, were among the first American women lecturers. Although they were born into an aristocratic slave-owning family in South Carolina, the sisters condemned slavery, joined the anti-slavery movement, and moved north to Philadelphia.[30] Their background as former slave owners marked the Grimké sisters as important allies within the abolitionist movement. Their religious and moral convictions of the evils of slavery brought the sisters to speak publicly for the antislavery cause, and they became the first American-born women to make a public speaking tour. [31] Although they faced criticism for their public and political involvement in abolitionist campaigns, they defended their actions by arguing that “...Men and women are CREATED EQUAL! They are both moral and accountable beings and whatever is rights for a man to do is right for woman.”[32] For the Grimké sisters, inactivity where abolition was concerned was unthinkable:

"We do not, then, and cannot concede the position, that because this is a political subject women ought fold their hands in idleness… the denial of our duty to act, is a bold denial of our right to act; and if we have no right to act then may we well be termed ‘the white slaves of the North’- for like our brethren in bonds, we must seal our lips in silence and despair."[33]

The Grimké sisters are also notable for their confrontation of racism. Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States, written by Angelina Grimké in 1837, expressly noted the equality of all women, and implored her fellow white woman to treat their African American sisters...

as equals, visit them as equals, invite them to co-operate with you in Anti-Slavery and Temperance and Moral Reform Societies- in Maternal Associations and Prayer Meetings and Reading Companies... Go to their places of worship; or, if you attend others, sit not down in the highest seats, among the white aristocracy, but go down to the despised colored woman’s pew, and sit side by side with her.[34]

Having spoken to the necessity of white women interacting with their African American sisters, Angelina Grimké addresses African American women:

...now we would tenderly solicit their indulgence whilst we throw out some suggestions to them [African American women]. You, beloved sisters, have important duties to perform... duties no less dignified and far more delicate and difficult. You daily feel tho [sic] sorrowful effects of the prejudice... but we entreat you to “bear with us a little in our folly,” for we have so long indulged this prejudice... as women, as Christians, we are ashamed of our folly and sin, and we entreat your aid to help us to overcome and abandon it.[35]

Angelina Grimké’s text shows a both recognition of and aversion toward the racial discrimination present in the free States. The sisters were also concerned with racism within the Society of Friends, or Quakers. Following their move to Philadelphia, the Grimkés revolted against the segregated seating enforced by the Philadelphia Society of Friends by sitting on the “Negro bench.”[36] In 1839, the sisters were asked to provide information on the prejudice within the American Society of Friends. Sarah Grimké reached out to Sarah Douglass and asked if she would write her testimony of prejudicial treatment within the Friends. This letter and Sarah’s own reply was published in the pamphlet Society of Friends: Their View of the Anti-Slavery Question, and Treatment of the People of Color.

Lucretia Mott

Like the Grimkés and Maria W. Stewart, Lucretia Mott was an abolitionist, women’s rights advocate, and public speaker who recognized the impact and injustice of racism. Unlike other abolitionists, Mott viewed African Americans as equals, and recognized that racial prejudice was injurious as slavery was. Lucretia Mott made efforts to form personal relationships with African American men and women, like her fellow PFASS members Forten-Purvises and the Douglasses, but also strove to expand her circle.[37] In 1833 Mott wrote about her activities, citing her work in the organization of six anti-slavery meetings for people of color and noting that three more were planned “...which will embrace all.”[38] Understanding of the effects of racism, Mott consistently devoted herself to promoting racial equality throughout the course of her life.[39] Writing to Phoebe Willis in 1838, Mott acknowledged the importance of interracial relationships:

"We cannot succeed in persuading the colored people who reside here that their interests would be promoted by scattering themselves more thru [sic] the country- they are a gregarious people & natural enough that they should be so while we exclude them from all other society than their own."[40]

At the 1838 meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society, women’s public involvement in abolitionist campaigns was a pivotal issue that contributed to the split of the Society. A vote “deciding that all persons be admitted to act with this body” in the AASS was taken and the motion was approved,[42] though narrowly, as the votes in support numbered 180 and the votes against numbered 140. [43] Following this resolution, women were elected to leadership positions within the AASS, though this too, was met with strong opposition. The issue of women’s public and political involvement- and other radical beliefs, such as the denunciation of the Constitution as a pro-slavery document, led to the fragmentation of the abolition movement. Nonetheless, the explicit inclusion of women signaled growing support from men and women for women’s public activity within the abolition movement.

Notes:

[12] Williams, Carolyn. ‘The Female Antislavery Movement: Fighting Racial Prejudice and Promoting Women’s Rights in Antebellum America” The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women's Political Culture in Antebellum America, edited by Jean Fagan Yellin, John C. Van Horne, Cornell University Press, 2018, pp. 160.

[13] Sumler-Lewis, Janice. "The Forten-Purvis Women of Philadelphia and the American Anti-Slavery Crusade." The Journal of Negro History, vol. 66, no. 4, pp. 282- 285.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Sumler-Lewis, pp. 283.

[16] Williams, pp. 164-165; Sumler-Lewis, pp. 283.

[17] Williams, pp. 164-165.

[18] Sterling, Dorothy. We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century. W. W. Norton & Company, 1997, pp. 125.

[19] Grimké, Charlotte Forten. The Journals of Charlotte Forten Grimké. Oxford University Press, 1988, pp. 140.

[20] Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. “Discrimination Against Afro-American Women in the Woman’s Movement, 1830-1920.” Sharon Harley, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, The Afro-American Woman: Strugges and Images, Black Classic Press, 1997, pp. 19.

[21] Yee, Shirley J. Black Women Abolitionists: A Study in Activism 1828-1860. University of Tennessee Press, 1992, pp. 94.

[22] Terborg-Penn, pp. 19.

[23] Friedman, Lawrence J. Gregarious Saints: Self and Community in American Abolitionism, 1830-1870. Cambridge University Press, 1982, pp. 166-167.

[24] Friedman, pp. 166.

[25] Lerner, Gerda. Black Women in White America: a Documentary History. Vintage Books, 1992, pp. 83.

[26] Stewart, Maria. Lecture, Delivered at the Franklin Hall, Boston, Sept. 21, 1832. New York Public Library.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Lerner, pp. 83.

[29] Yee, pp. 115.

[30] Dudden, pp. 7.

[31] Lerner, Gerda. “The Grimké Sisters and the Struggle Against Race Prejudice.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 1.

[32] Grimké, Sarah. Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Woman: Addressed to Mary S. Parker, Boston, 1838, pp. 16.

[33] An Appeal to the Women of Nominally Free States Issued by an Antislavery Convention of American Women, Boston, 1838, p. 13-14.

[34] An Appeal, pp. 13-14.

[35] An Appeal, pp. 60-62.

[36] "The Grimké Sisters and the Struggle Against Race Prejudice," pp. 123.

[37] Faulkner, Carol. Lucretia Mott's Heresy: Abolition and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011, pp. 55-60. Williams, pp. 168.

[38] Mott, Lucretia. “To Phoebe Willis.” 18 Mar. 1833. Mott Correspondence, Friends Historical Library.

[39] Faulkner, pp. 60; Williams, pp. 168.

[40] Mott, Lucretia. “To Phoebe Willis.” 7 Nov. 1838. Mott Correspondence, Friends Historical Library.

[41] DuBois, Ellen Carol. Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848- 1869. Cornell University Press, 1978, pp. 24.

[42] Fifth Annual Report of the Executive Committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society. New York, 1838, pp. 28.

[43] Ibid, pp. 30.

Tags

- belmont-paul women's equality national monument

- frederick douglass national historic site

- reconstruction era national historical park

- women's rights national historical park

- abolition

- women's history

- african american history

- political history

- civil rights

- anti-slavery

- religious history

- pennsylvania

- new york

- massachusetts

- education history

Last updated: November 19, 2020