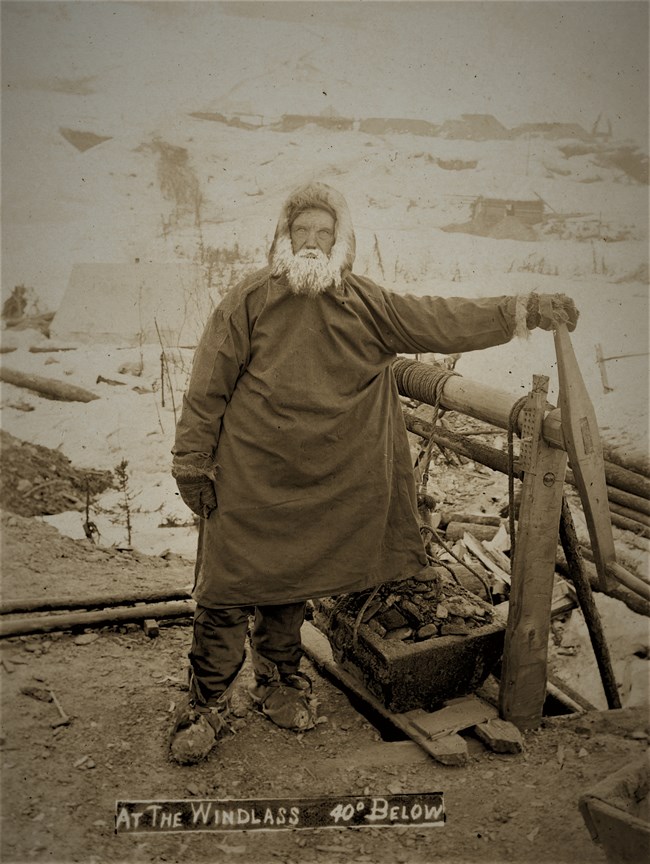

Glass photographic negative, author’s collection "Many of the shafts have smoke boiling out of them like a furnace, and at many more the men are at work hoisting the dirt that has just been thawed. The usual outfit is a windlass, a rope and a clumsy wooden box—a miner’s ‘bucket’—that holds about 150 pounds of dirt."—San Diego Union, February 17, 1898 In the 1880s and 1890s, gold-seekers along the Yukon River corridor faced serious obstacles—they had to haul supplies long distances, the summer season was vexingly short, and much of the gravel they needed to reach was locked in permafrost. The last of these challenges limited miners to working shallow creek gravels during the summer months, while (to their consternation) the richest deposits of gold lay deeper underground.

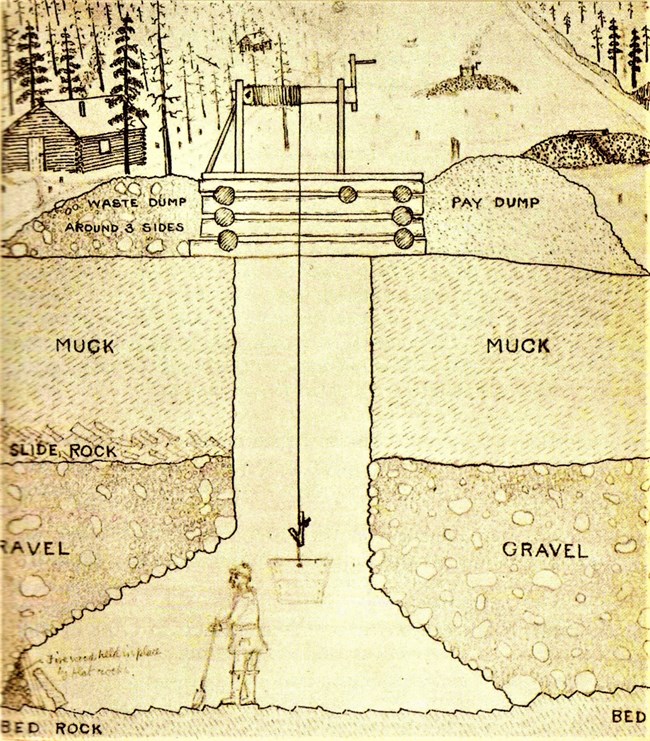

University of Washington Special Collections, William E. Meed Collection A novel approachIn the late 1880s, a few prospectors in the Fortymile River area, near the U.S.-Canada border, began using fire to reach underground gold deposits, but the practice was not fully embraced until gold was discovered at Birch Creek in 1893. As Circle City emerged as a supply depot and log cabin boomtown near the new diggings, a reporter for the Sun and New York Press explained the new approach. Instead of spending all winter in town loafing in the dance-halls, at least two miners stuck by their claims: They found that a big fire burning all night would thaw out a couple inches of gravel. In the morning they would scrape away the remnants of the fire, lug their gravel into the cabin, and at night build another fire. They kept this up all winter, and when the ice went out in the spring they had a big pile of dirt ready to pan. They washed $16,000 of dust out of that pile of dirt for their winter’s work. The power of fireWhen “burning down,” miners waited until winter when the intense cold froze the creeks and groundwater—otherwise their prospecting holes would flood and be rendered useless. The shaft needed to be 4 x 6 feet wide to allow for a human being and an excavation bucket; a windlass erected over the hole helped to hoist the heavy material to the surface. Day after day the ‘driftman’ removed the ashes and used a pick and shovel to dig out the soggy, melted dirt before adding more wood for the next bonfire. The goal was to excavate down to the level of bedrock where over eons gravity had deposited gold dust and nuggets. Then the miners started the ‘drift,’ moving horizontally to collect the richest layer of gold-bearing gravel. Large flat rocks were used to hold the wood in place and they absorbed heat to extend the thaw.

University of Washington Special Collections, George Cantwell Collection Dangers undergroundIn 1897, when Circle City miners rushed upriver to Canada’s Klondike goldfields, they brought their knowledge of “burning down” with them. As the journalist Tappan Adney observed on Eldorado Creek: The sun, like a deep-red ball in a red glow, hung in the notch of Eldorado; the smoke settling down like a fog (for the evening fires were starting); men on the high dumps like spectres in the half-smoke, half-mist; faint outlines of scores of cabins; the creaking of the windlasses—altogether a scene more suggestive of the infernal regions than any spot on earth. Although the permafrost usually held tunnel ceilings in place, cave-ins did occur, as did accidents like buckets falling onto the heads of men below. However, the most dangerous threats to drift miners were the residual smoke, that irritated the eyes and could blind with prolonged exposure, and the noxious fumes that lingered underground and could kill by asphyxiation. In such cases, the man down below needed the strength to hold onto the bucket while his comrades pulled him to safety.

Out with the oldUsing fire to reach pay dirt was always slow, costly, and dangerous, and soon a new technology began to take its place. Steam boilers rigged with rubber hoses and steel pipes (called “steam points”) could thaw gravel more efficiently and without threatening the lives of the miners. Even so, wood fires continued to be the method of necessity along the Yukon River and wherever miners lacked the means to purchase and transport boilers. Though little evidence remains of ‘burning down’ in Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, visitors today can see multiple examples of steam boilers that were used to reach gold deposits into the 1930s. Further Reading:Yukon River Wild CatsSan Francisco Chronicle, July 24, 1898, 16by Ben S. Goodhue

It is difficult to mine alone in Alaska. You should have at least one partner, so that you can work to advantage, alternating in the hole and on the windlass. Old California miners find the process of mining in Alaska a revelation. Nature, instead of aiding, is in opposition during nine months of the year. During the sluicing season the methods are about the same as employed in placer mining in California. At nearly every turn obstacles must be overcome by human energy. In sinking a single shaft you consume from five to fifteen cords of wood in burning down to bedrock. This wood must be cut often when the temperature is 40 to 70 below zero. Green wood is the best for sinking, as it burns longer. In drifting, dry wood is necessary, with a covering of green logs to confine your fire in bringing down the pay dirt only, avoiding the handling of much waste. A drifting fire is a nice piece of work, resembling the fires in a charcoal pit if properly made. The amount of preparation before beginning to mine is considerable. In a country where tools are so scarce you are often compelled to depend upon your ingenuity alone. In fact, you must resort to a couple of oil cans if you want a stove, fruit cans joined together by swelling the ends if you want a stovepipe, stripping a birch tree if you want a broom, corrugating a slab if you want a washboard, etc. Before you commence you need rope, ladders, windlass and frame, a bucket for hoisting dirt, a mud box for panning and a cabin to live in. With these preparations completed, you can go to work. Sinking is easy compared to drifting. In this work, if you have any physical weakness it is sure to assert itself. The work is hard enough, but to endure the stifling gasses, affecting the eyes, heart and respiration, will severely test your staying qualities. I am blessed with a pair of strong lungs that were taxed to the fullest extent to keep the machinery in motion. I could often feel, almost hear my heart beat with a heavy pounding and was often compelled to grope and feel my way to the shaft to be hoisted as quickly as possible by the man on the windlass, who stood by in case of such emergency. In our drift we were finally compelled to dig an air vent at the expense of an infinite amount of labor. To my surprise I seemed to bare the strain well. After his being in the last drift a week or ten days, Mr. Taylor’s eyes gave out, becoming bloodshot and affected almost to blindness from which he recovered very slowly. In places I found some very rich dirt. To pick up nuggets to the amount of thirty to forty dollars in a space as big as my two hands was something of a solace. Windlass work is also hard on a man, generally laming the back severely until he becomes accustomed to it. As you are constantly exposed to the cold, you are apt to freeze your hands or feet. I experienced the sensation of a frozen nose one day while at the windlass while the temperature was down to 56 below zero. There is no real pain, however. The member feels unusually long, turning white, and gives the impression of being appended somewhat misplaced on my countenance. The old method of rubbing snow to take out the frost is not as good, I believe, as to rub the frozen part with a dry woolen. If you are wearing a woolen mitt and your nose or face is frozen, rub it with that... All that is necessary is to restore the circulation. If this can be done without creating moisture you will have no further difficulty. |

Last updated: March 12, 2021