|

To best understand John Muir, it’s best perhaps to reflect on those people who most influenced him. In 1870, geologist Joseph LeConte, a University of California geologist, observed a Glacier Point rockslide from the view of Bridalveil Meadow with Muir. LeConte agreed with the naturalist’s theory that a river of ice, in part, shaped Yosemite’s mountains. (Muir doubted that the Valley had been created solely by earthquakes.) Le Conte said of Muir: “Mr. Muir gazes and gazes and cannot get his fill. … Plants and flowers and forests, and sky and clouds and mountains seem actually to haunt his imagination.” Muir corresponded with LeConte, sending him ice hunks from living glaciers. LeConte is forever honored in Yosemite National Park through the LeConte Memorial Lodge, a National Historic Landmark, in the Valley. (Read Muir's first published article on glaciers and more on Yosemite's geology.) In 1871, Transcendentalist-thinker Ralph Waldo Emerson saw Yosemite, which reminded the New Englander of White Mountain Notch. Upon meeting, Muir showed Emerson his hundreds of pencil sketches of peaks and valleys. They visited the Mariposa Grove, guided by Galen Clark, who publicized the sequoia stand in 1857. Muir said to Emerson in the grove: “You are yourself a sequoia. Stop and get acquainted with your big brethren.” Emerson called Muir a “new kind of Thoreau” who gazed at sequoias of the Sierra instead of scrub oaks of Concord.

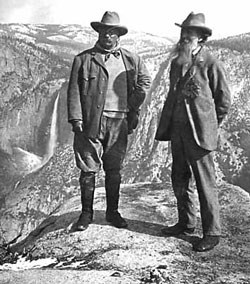

In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt posed with John Muir for pictures on Overhanging Rock at the top of Glacier Point and camped in a hollow there to awake to five inches of snow, which delighted Roosevelt. Roosevelt had sent Muir a letter asking to meet him in Yosemite: “I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you.” At their meeting, Muir spoke of environmental degradation, like development, and asked for another layer of protection as a national park to improve management. Muir convinced both Roosevelt and California Governor George Pardee, on that excursion, to recede the state grant and make the Valley and the Mariposa Grove part of Yosemite National Park. This joining together of the 1864 state grant lands with the 1890 national park lands occurred during Roosevelt’s presidency in 1906. |

Last updated: March 1, 2015