It's not hard to imagine that Yosemite Valley is a mecca for rock climbing. It's a granite playground. Today, sport and amateur climbers alike flock to the park to test their skills. In 2014, professional climber Alex Honnold climbed seven routes on El Capitan in seven days. Just yesterday I saw a six year old squeal with accomplishment from the top of her first pitch. Yosemite's walls have been home to all different kinds of rock climbing, tracing the history and development of the sport. Yosemite saw its first type of climbing born out of adventure, then one that danced intimately with trepidation and danger, and then ushered in a dusty, beloved counterculture form of rock climbing. The Yosemite Museum has relics of all three of these monolithic stages.

First Climbers

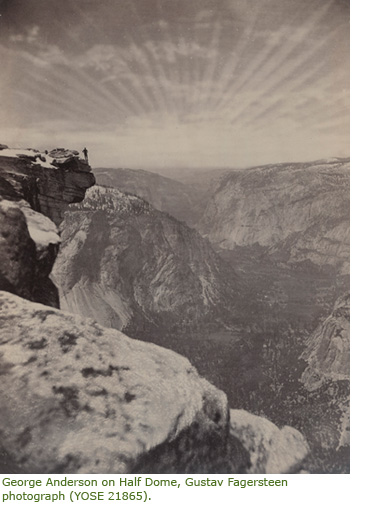

The collection starts right at the beginning with a spike from the very first documented ascent of Half Dome in 1875 (YOSE 155). That year, George Anderson climbed the east slope, spending a week drilling holes for eyebolts and a skein of fixed ropes. The slope, only a forty-five degree incline, may not sound difficult, but its smooth flawless granite surface made it a (venerable) challenge. Anderson is considered the first technical climber in Yosemite. The first known non-technical climber was none other than famous wilderness guru, John Muir. On one of his shepherding treks across Tuolumne, Muir climbed to the top of Cathedral Peak—a climb that is today rated a Class 4, meaning most climbers need to use ropes to scale it. Unroped and solo, the thirty-one year old Muir completed the climb among countless other experiences scrambling around ledges and gullies. Unfortunately, he left few records of these climbs, leaving Anderson to be the first on paper.

The collection starts right at the beginning with a spike from the very first documented ascent of Half Dome in 1875 (YOSE 155). That year, George Anderson climbed the east slope, spending a week drilling holes for eyebolts and a skein of fixed ropes. The slope, only a forty-five degree incline, may not sound difficult, but its smooth flawless granite surface made it a (venerable) challenge. Anderson is considered the first technical climber in Yosemite. The first known non-technical climber was none other than famous wilderness guru, John Muir. On one of his shepherding treks across Tuolumne, Muir climbed to the top of Cathedral Peak—a climb that is today rated a Class 4, meaning most climbers need to use ropes to scale it. Unroped and solo, the thirty-one year old Muir completed the climb among countless other experiences scrambling around ledges and gullies. Unfortunately, he left few records of these climbs, leaving Anderson to be the first on paper.

After Anderson's, very few climbs took place at Yosemite. Up until the 1930s, most climbs were Muir style: un-roped explorations of ledges and ridges. California climbers lacked the roping techniques that had been developed and improved in Europe since the 1850s and this severely barred them from more challenging climbs. These skills finally made it to California in 1931. In the summer of 1930, Harvard mathematics professor Robert Underhill climbed in British Columbia with Francis Farquhar, editor of the Sierra Club Bulletin—an esteemed journal of the San Francisco-based climbing and conservation organization, the Sierra Club. Underhill had spent previous years climbing in the Alps and he shared with Farquhar the techniques of roped climbing that he had learned there. In turn, Farquhar brought these skills to his most promising climbers at the Sierra Club and he also solicited an article by Underhill in the February 1931 issue of the Bulletin, “On the Use and Management of the Rope in Rockwork.” This 20-page treatise ignited Bay Area climbers and mountaineers and they set out to master the new form. Rope climbing opened up countless new routes and challenges and allowed for climbers to find their space high above a world that was shattering beneath them.

Drafted Pitchers: Fear and danger on the rocks

Fritz Lippman and Torcom Bedayan were attempting to ascend a “sinister-looking” slash in a wall to the left of Arrowhead Spire when the first bombs descended on Pearl Harbor. On the side of the rock, the boys were the image of a young man in the 1940’s: confronted with violent, gruesome challenges, fueled on danger. Though not from this climb, the Museum has Nylon ½ inch 3-ply rope from the 1940s (YOSE 75853). Lippman had already failed twice to ascend the Chimney, impeded by room-size boulders causing “untold problems.” Yet, he began his way up what he later called “a suicide route.” He had only “poor direct-aid pitons” to take on a “horror pitch” from which “retreat was impossible.” His climb, in the end successful, was recounted in the Bulletin and later criticized for being irresponsibly dangerous. At the time, it must have seemed reckless, near-disrespectful to wager your life in recreation when soon after his peers would be drafted to do the same thing out of necessity.

The 1960s: hanging loose

Twenty years later, climbers came to Yosemite Valley to do what Lippman and Bedayan had unknowingly done: escape. Climbers of the 1960s ushered in a completely new era and culture of climbing, circled around the legendary Camp 4. The Yosemite Museum remembers these years with Jumar devices used for ascending climbing rope and pitons removed from a climb on Washington Column called “The Prow” done by National Park Ranger Ben Doyle, among other pieces of equipment (YOSE 233570). What makes these rusty and worn objects worth keeping is that they pinpoint the enormous influence Camp 4 and Yosemite had on incubating a new climbing culture in the 60s. Yosemite Valley was the center of the rockclimbing universe. Nonconformists, misfits, beatniks, drop outs, and adventurers came together at this dusty campsite to hang loose and stir together their energies into a love for thrill and environment. While their peers were serving big corporation internships or making a killing in financial highrises, climbers at Camp 4 were eating peanut butter sandwiches from their vans and sharing stories behind uncombed hair. Many also credit the camp with the creation of slacklining, a simple sport of balancing on a tightrope tied across two trees, which the climbers enjoyed on their rest days and which are today found on almost every college campus. The camp is a part of history; it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2003. Linda McMillan, former Vice President of the American Alpine Club, said, “What makes this dusty little campground so historic and unique is its freewheeling, dynamic spirit and the people drawn to it over the decades. Camp 4’s spirit epitomizes the spirit of the American West—restless, unconventional, inventive, and filled with hope.”

After the 1980s, climbing took on a different tone as sport climbing started to dominate the scene. The new tone was adrenaline-oriented and led to wild epics and new rules. Focus shifted to Europe, where throughout France and Italy sport climbers used bolts, pre-rehearsed moves, and competitions that emphasized difficulty over the visceral and cultural experience of climbing. And yet today, Yosemite still offers one of the most vast and dynamic environments for all climbers. Whether coming to share stories around a bonfire at Camp 4, or to climb up El Cap seven times in one week, the Valley is still a playground, a mecca, and a home.