Some describe winter in Yosemite as magical.

For many people, their visit to Yosemite National Park is filled with activities… typically those of the summer variety: hiking, backpacking, biking, swimming, rafting, climbing, sightseeing, horse riding, just to name a few.

But, what about winter? A smaller number of visitors experience Yosemite in winter. It is a tranquil season here, when snow blankets the trails and roads that so recently were teeming with people buzzing around hurriedly. It offers quiet moments to explore the park more intimately and to engage in different activities, such as skiing or snowshoeing.

In the 1850s and 60s as pioneers began to explore and settle throughout the Sierra and Yosemite, winter was a time when much of the mountains were abandoned as people migrated to the snow-free zones of the lower foothills. Over time, people such as James Lamon began to push through that winter barrier and live year-round in Yosemite Valley. However, these hearty pioneers were rare, winter visits to Yosemite Valley were minimal, and the fall pilgrimage to lower elevations continued into the early 1900s. However, on at least some small level, the start of wintering in Yosemite had begun and primitive outings on skis, snowshoes, and sleds had commenced.

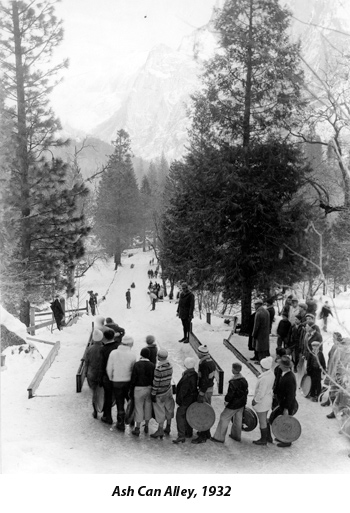

It wasn’t until 1916, along with the creation of the National Park Service, that winter sports began to truly evolve in Yosemite Valley. Employees created an 800-foot snow slide near Curry Village and enthusiasts were creative in finding devices to slip and slide their way down. Using trash can lids or hotel trays, the run became known as “Ash Can Alley.” Local residents and employees longed for winter and a time when the park became a private playground of sorts. While some enjoyed the lack of winter crowds, others wanted to put Yosemite on the map as a winter destination.

Stephen T. Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, believed strongly, that “Yosemite is a winter as well as a summer resort…That it has not been more patronized during the winter months is due partly to limited accommodations and partly to lack of publicity.” In some ways he was right, and his hopes for Yosemite later came to fruition.

In 1926 the All-Weather Highway, known today as Highway 140 and the El Portal Road, was completed. With new convenient all-year access, Yosemite began to gain even more attention. Unprecedented numbers of tourists flocked to the park in summer and winter, changing the dynamics of the place forever. New activities were sought after to entice visitors throughout the year, but still winter didn’t draw tourists the way that summer did. Don Tresidder, president of the concessioner at the time, began to envision even bigger things for Yosemite’s future. After visiting Switzerland with his wife for the 1928 Winter Olympics, he was inspired to make Yosemite the “Switzerland of the West.” That year he formed the Yosemite Winter Club (still in operation today) to “encourage and develop all forms of winter sports [and] to advertise and exploit the great advantages, beauties and healthy benefits of winter in the California Sierra to all the lovers of outdoor life.” The Yosemite Winter Club was the beginning of an idea, and the winter sports that resulted from it were numerous.

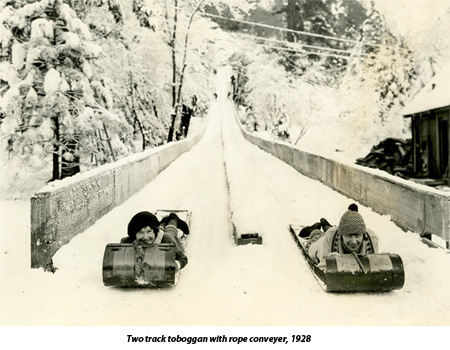

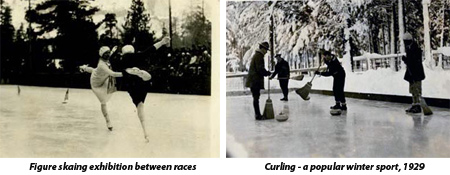

The shaded southside of Yosemite Valley remains coldest during the winter months and became a natural place to enhance winter activities. Toboggan runs were built just west of Camp Curry, the Camp Curry parking lot was flooded in order to create a large ice-skating rink, nearby meadows and roads became the canvas for dog sled rides, sleighing and skijoring (skiing behind a horse with a tow rope). Hockey games, curling, and speed and figure skating were also popular out on the ice, and a small ski jump was built on a glacial moraine near the present day stable. The dream Tresidder had was becoming a reality, but he had his sights on more. In addition to enticing visitors to come in winter, he wanted Yosemite to host the Olympic Winter Games in 1932.

The bid for the Olympics was an exciting time for Yosemite, as it was to be the first Winter Games in the United States. It was much smaller than today’s Olympics, with only 17 countries competing in 14 events. Compare that to this year’s record 88 nations competing in 98 different events! In 1932, the three established snow sport areas competing against each other were Yosemite, Lake Tahoe, and Lake Placid, NY. Each had their pros and cons and in the end Lake Placid won the bid. While Yosemite boasted about its adequate lodging, and its newly built ice rink, it lacked other venues for the majority of the Olympic events. Tresidder had hoped that ice skating would put Yosemite on top; that along with it being such a premier tourist destination. However, in the end, it was felt that California had little experience with competitive events, especially those of the winter variety.

Although Yosemite didn’t host the Olympics, it did grow into more of a winter destination. By then, it claimed the best ice rink in California and the west coast speed skating tryouts for the 1932 Olympic Winter Games were actually hosted at the Camp Curry rink.

Additionally, in the winter of 1928-29 Tresidder established the Yosemite Ski School, the first in the west, which was run by a top Swiss instructor. Regardless of the expanded assortment of winter activities, Ash Can Alley remained the most popular, drawing large crowds which required up to seven rangers to assist with managing traffic, people, and keeping the pulleys in working order. While these activities were popular, people were looking for other places to further challenge themselves. The Winter Club continued to lead the way.

During the early 1930s, activities began to broaden to areas outside of Yosemite Valley. With the completion of the Wawona Tunnel, the area south near Chinquapin began to attract folks for downhill skiing. Explorations by Winter Club members continued to the east, looking for other ski venues and they found the perfect spot six miles over. Tresidder supported the development of that area, and thus was the birth of Badger Pass. In 1933 with popularity for skiing growing, and the need for related services following suit, a day lodge/ski hut was added on to the service station at Chinquapin (12 miles south of Yosemite Valley at the junction of today’s Glacier Point Road). These amenities were welcomed, but were barely adequate. Regardless, 10,000 skiers visited Badger Pass during the following season! In the beginning downhill skiing required people to hike up the hill on their own, allowing them to fit in just a handful of runs during the day. In 1934-35, a rudimentary electric lift was installed at Badger Pass, carrying a few skiers at a time, which greatly improved people’s experience beyond the days of side stepping their way up the mountain. And this was only the beginning.

Tresidder was ahead of his time. He was forward thinking in his ideas of promoting and building up winter sports and the venues to support them. The idea of avid winter sporting in Yosemite was hard for many to imagine then and still is for some today. The same could be said for me.

When I first arrived to Yosemite Valley during the heat of the summer months and under the crush of the summer crowds, I thought nothing of winter and what it would be like. Four months later, as I ice skated at Curry Village under a full moon with a light snow beginning to fall, I paused and looked around. The granite walls were brilliant in a way I’d never seen them. The fresh snow was sticking to every crack and crevasse only making the rock landforms more breathtaking, and more alive with a depth that is not as prominent in summer. As my skates glided along the ice, I was mesmerized by how drastically different the place was, how different it felt. It was magical.