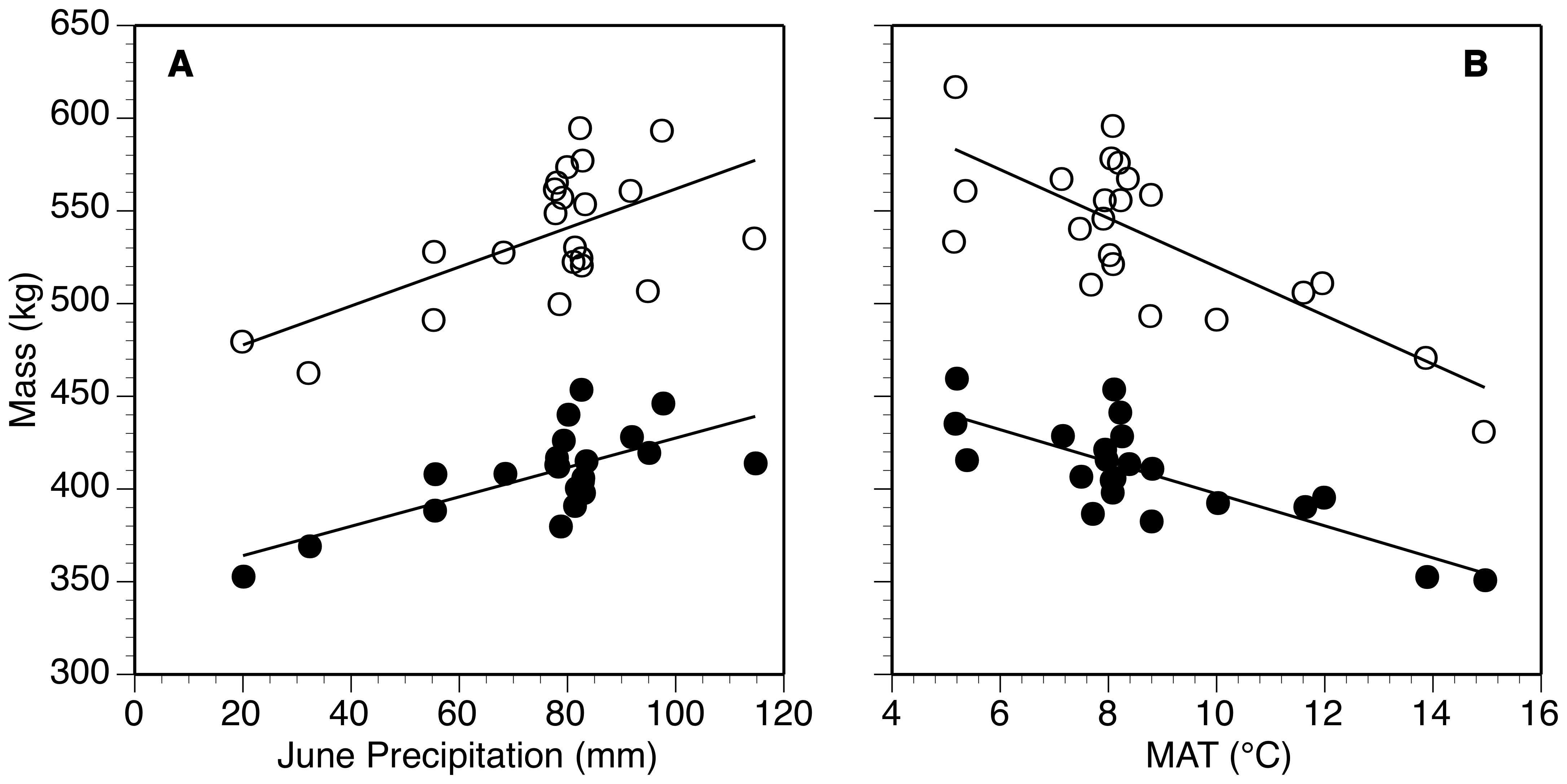

Let’s back up. 2000-pound bulls aren’t shrinking overnight like socks in the drier. But warm-weather bison just don't seem to bulk up as much as their cold-weather counterparts. In 2013, Kansas State University researcher Joseph Craine surveyed over 290,000 bison in 22 herds (including Theodore Roosevelt). He found that warmer climates meant lower body weights for both males and females. The differences could be profound: an average 6.5-year-old bull on Ordway Prairie in South Dakota (average temperature: 42°F) weighs in at 1,887 lbs, while an average bull the same age at the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge in Oklahoma (average temperature: 60°F) measures a paltry 1,314 lbs. The differences were largest in adult males—for every 1°F increase in temperature, they were an average of 20 lbs lighter.

Left: bison mass plotted against precipitation at the 22 sites in the study; right: bison mass plotted against Mean Annual Temperature (MAT). Open circles represent average weights for males, while closed circles represent females. (From Craine, 2013)

What’s behind this pattern? One clue lies in bison’s grass-heavy diet. Grasses in warmer environments produce less nitrogen in their leaves, which means less protein crucial for weight gain. There is also evidence that higher levels of carbon dioxide may change the chemical balance of the prairie itself. When scientists looked at a century of preserved plant specimens, they found leaf nitrogen levels have been on a decline since 1906.

Why do we see these long-term changes? One theory suggests that higher carbon dioxide levels cause more nitrogen to be locked away in long-lived plants and organic matter, out of reach of prairie grasses — and hungry bison.

A second key to the mystery of the shrinking bison may be the habits of bison themselves. Historically, bison herds migrated more than a thousand miles each year to find the most nutritious food sources. Today, the vast majority of bison live on small, fenced preserves. Bison in warmer areas with low-protein grasses can’t compensate by finding other protein-rich plants or better grazing grounds. In short, for fenced-in bison, the grass may really be greener on the other side.

Currently, Theodore Roosevelt is one of the chilliest sites surveyed, with an average temperature of just 42°F. But this may not be true for long — by the year 2100, scientists predict another 8°F of warming beyond the 2.5°F already witnessed here in the last century. If the link between climate and weight proves true over time, the warming atmosphere may put our bison on weight-loss program of more than 150 lbs over the next century.

Are we seeing any evidence of shrinking bison here in Theodore Roosevelt? During bison roundups every 3-4 years, we collect data on the weight, age, sex, and a DNA sample from each member of our herd. However, we need many more years of data to begin to see any trends over time. While we wait and see, however, there are steps we can take to protect bison over the long term.

Key to the bison's future is the idea of resiliency—a species’ ability to “bounce back” and overcome new challenges in its environment. In this case, resiliency in the face of global warming means access to more diverse, nutritious food sources. Examining plant material in bison poop shows that herds in warmer areas already rely more on shrubs and other plants than on grasses. Preserving the natural biodiversity of grassland ecosystems may be the first step towards protecting bison themselves.

We don’t know exactly what impacts global warming may have on the bison, or the park. But we do know that just as bison are a key player in the the prairie ecosystem, any changes in the ecosystem will impact our bison—in ways that aren’t always easy to predict.

Return to the Bison Blog home