Follow along on our International Underground Railroad Month Social Media Takeover via this article series.

Even if you are not participating in our social media takeover, one of the many ways that organizations can engage with International Underground Railroad Month is through social media. The tools below will help you develop a plan for social media during International Underground Railroad Month.

On This Page

What makes a good social media post? Use these tips and tricks to create your own posts for International Underground Railroad Month.

Learn more about hashtags that will connect you with other International Underground Railroad Month content.

Find photos of listings in the Network to Freedom Program.

Need some help creating content for social media? Customize our ready-made posts.

What happened on this day in September related to the Underground Railroad? Use this tool to find out.

What makes a good post?

Navigating social media can be challenging. What do I post? How do I grow my network? What is a retweet? This is complicated in that every social media platform is slightly different, and thus have unique sets of best practices. Though, there are some best practice that can be carried throughout multiple social media platforms.

-

Keep it snappy: Keep the text of your post concise. Say what needs to be said without rambling, and leave room for conversation and thoughts from your network.

-

Be thoughtful: Each word you choose to include in a social media post matters. Choose your words carefully, and make sure the words you choose accurately represent what you want to say.

-

A picture is worth a thousand words: High quality photographs draw in social media users. Don't forget to provide an image description for users utilizing a screen reader, and do not use copyrighted images.

-

Relevance: If you came across this post/video/photo, would you stop and engage with the post? Put yourself in the audience's shoes, and post with them in mind.

-

Connect: Connect with your community! Use hashtags to connect with new users, work with others and tag them in your posts, and use social media as a vehicle to show the "network" in the "network to freedom."

Hashtags

Hashtags allow users to cross-reference content with a similar subject or theme. So, for example, if someone sees a post tagged #undergroundrailroad, they may spend time scrolling through other posts tagged #undergroundrailroad see similar content, and thus find new people, organizations, and platforms which they might follow or engage with. Hashtags are a very important piece of posting on social media.

Although we encourage you to perform your own research on hashtags, here are some possible hashtags to consider when posting for International Underground Railroad Month:

- Any Underground Railroad Post During September: #UGRR #InternationalUndergroundRailroadMonth #September

- If it is related to the Network to Freedom: #NPSNetworkToFreedom

-

If it is related to the National Park Service: #FindYourPark #EncuentraTuParque

- If it is related to Hispanic/Latinx Heritage Month: #LatinxHeritageMonth #HispanicHeritageMonth

Photos from Network to Freedom Listings

If you need high quality photos of Network to Freedom listings to talk about Underground Railroad history on social media, consider looking through these photo galleries. It is the user's responsibility to assess copyright or other use restrictions.

Ready-Made Posts

Need help creating social media content? Not to worry. Feel free to use and customize the text and images below during International Underground Railroad Month. Don't forget to tag the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program (@NPSNetworkToFreedom) on Facebook and Instagram.

Post: Start of International Underground Railroad Month

To download the image, click on the image. Right click in the pop up window to save the image.

Public Domain

It’s officially September, which means it is International Underground Railroad Month! Since 2019, states across the country have declared September as International Underground Railroad Month in an effort to highlight and bring awareness to the Underground Railroad stories in the United States and beyond.

This month we are excited to highlight [INSERT LOCATION/ORGANIZATION NAME]’s connections to the Underground Railroad over the next several days.

Photo Credit: NPS Photo

#InternationalUndergroundRailroadMonth #NPSNetworkToFreedom #UndergroundRailroad #UGRR

Post: What is the Underground Railroad?

To download the image, click on the image. Right click in the pop up window to save the image.

NPS Photo

The National Park Service’s National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program (@npsnetworktofreedom) defines the Underground Railroad as “resistance to slavery through escape and flight.” But what does that really mean?

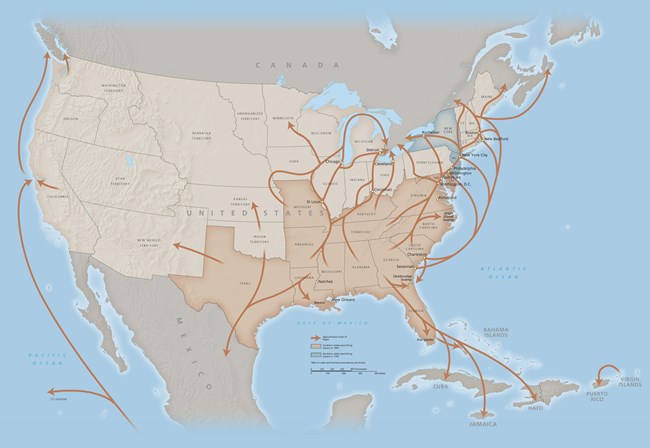

When many people learn about the Underground Railroad for the first time, they learn about a very regimented movement taking place from 1830-1860 where white abolitionist allies ushered freedom seekers from one location to another until they reached freedom in Canada. This is problematic in many ways. The Underground Railroad would not have existed without the brave men and women who made the decision to exercise their autonomy, escape from their enslavers, and claim their freedom. Freedom seekers traveled in whatever direction necessary to find a destination where they could live freely. As long as people enslaved others, freedom seekers escaped to try and build a better life for themselves, and if possible, their families.

By reframing Underground Railroad history and focusing on the freedom seekers themselves, we have the opportunity to paint a more nuanced and accurate image of the Underground Railroad and debunk many wide spread myths. Wherever and whenever slavery existed, there were efforts to escape. We know free Black communities, and in some cases Indigenous tribes, came together to aid freedom seekers in their fight for freedom: not just Quakers and wealthy white abolitionists. We know that freedom seekers who made the decision to escape traveled not just North to Canada: but South to locations like Spanish Florida, the Caribbean and Mexico in order to reclaim their freedom. All of these puzzle pieces can help us understand the Underground Railroad as one of the first American Civil Rights movements.

Photo Credit: Routes of the Underground Railroad, NPS Photo

#InternationalUndergroundRailroadMonth #NPSNetworkToFreedom #UndergroundRailroad #UGRR

Post Template: Your Network to Freedom Story

September is International Underground Railroad Month! Since 2019, states across the country have declared September as International Underground Railroad Month in an effort to highlight and bring awareness to the Underground Railroad stories in the United States and beyond.

#DidYouKnow that [INSERT NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION NAME] is connected to Underground Railroad history? [2-3 SENTENCES ABOUT THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD STORY].

IF APPLICABLE: [INSERT NETWORK TO FREEDOM LISTING NAME] is listed as a [SITE/FACILITY/PROGRAM] in the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom (@npsnetworktofreedom).

Suggested Photo: Your Network to Freedom Listings

#InternationalUndergroundRailroadMonth #NPSNetworkToFreedom #UndergroundRailroad #UGRR

Library of Congress

Post: Why September?

September is International Underground Railroad Month! Since 2019, states across the country have declared September as International Underground Railroad Month in an effort to highlight and bring awareness to the Underground Railroad stories in the United States and beyond. But – why September?!

The idea of International Underground Railroad Month began in the state of Maryland: home to famous freedom seekers Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. Both Douglass and Tubman emancipated themselves in September: Douglass on September 3, 1838, and Tubman on September 17, 1849.

[IS THERE A CONNECTION BETWEEN YOUR SITE AND TUBMAN/DOUGLASS? CONSIDER ADDING 2-3 SENTENCES ABOUT THAT CONNECTION].

Photo Credit: These photos of Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass are from Library of Congress.

#InternationalUndergroundRailroadMonth #NPSNetworkToFreedom #UndergroundRailroad #UGRR

#OnThisDay in Underground Railroad History

Another way to engage with Underground Railroad history on social media is by posting about what happened "On This Day" in history. Curious about what is going on in Underground Railroad history in September? The list below provides some ideas of things taking place throughout Septembers' past.

Did we miss something? Feel free to e-mail us.

The Tabernacle Baptist Church in Beaufort, South Carolina was officially formed as an African-American congregation, under the leadership of the Rev. Solomon Peck of Boston, Massachusetts. The church would be renamed the Robert Smalls church, and he is buried on these grounds. The Robert Smalls Burial Site at Tabernacle Baptist Church is listed as a site on the Network to Freedom. Source: Robert Smalls Burial Site at Tabernacle Baptist Church Network to Freedom Application, p. 1

Frederick Douglass's Self Emancipation Day. Douglass and Anna Murray pooled their resources and purchased a train ticket. After borrowing free papers from a local sailor and friend, Douglass boarded the train dressed as a sailor and began his escape from slavery. After arriving in New York, he recalled, “I was FREEMAN, and the voice of peace and joy thrilled my heart!” Source: David Blight, Frederick Douglass Prophet of Freedom (Simon and Schuster: New York, 2018), p.80-83

Four men kidnapped free Black woman Eliza Jane Johnson from Ripley, Ohio. The four men, looking for a freedom seeker who escaped from Kentucky, mistakenly kidnapped the mother of five and imprisoned her. The free Black community of Johnson’s hometown, Sardinia, Ohio, traveled to Kentucky to advocate for Johnson’s freedom: first stopping at Red Oaks Presbyterian Church and Cemetery, a site on the Network to Freedom, to gather horses and other community members. Authorities released Johnson after five months. Source: Red Oaks Presbyterian Church and Cemetery Network to Freedom Application, p. 16

Freedom seekers Susan Borders, her three children, and a woman named Hannah arrive at John Cross’s farm in Farmington, Illinois. The local Justice of the Peace witnessed the freedom seekers travelling to Cross’s farm, and knowing Cross’s anti-slavery sentiments, suspected Underground Railroad activity, and prepared to arrest Cross and the freedom seekers. Borders, her children, Hannah, and John Cross were arrested; and Cross was indicted for harboring and assisting freedom seekers. The John Cross Burial Site at Hope Cemetery, located in Wessington, South Dakota, is a site on the Network to Freedom. Source: John Cross Burial Site at Hope Cemetery Network to Freedom Application, p. 7-10.

Freedom seeker Nelson Hackett is arrested. Nelson Hackett fled from his enslaver, Alfred Wallace, in Fayetteville, Arkansas in July of 1841. Prior to leaving town, Hackett stole a watch, an overcoat, and a horse. He then travelled across multiple states and arrived in Chatham, Canada in early September 1841. Wallace hired a local Sherriff to arrest Hackett on charges of theft. After confessing to the crime, a confession which Hackett later claimed was forced, authorities moved Hackett to a prison in Sandwich to await extradition. The Nelson Hackett Project, which tells the story of Nelson Hackett, is a program on the Network to Freedom. Source: The Nelson Hackett Project.

First Presbyterian Church in Green Bay, Wisconsin was officially dedicated. Reverend Jeremiah Porter, the church’s minister from 1840-1858, and his wife, Eliza Chappell Porter, and members of the congregation sheltered freedom seekers on church grounds on two separate occasions. The First Presbytarian Church is a site on the Network to Freedom. Source: First Presbyterian Church of Green Bay Wisconsin Network to Freedom Application, p. 1.

A group of about 20 freedom seekers, led by a man named Cato, armed themselves and began to travel from plantation to plantation and travelled toward the Edisto River, attacking white slaveholders and encouraging enslaved people to join them as they moved. By the time they reached the Edisto river, the group of nearly 60 freedom seekers encountered a white militia, and a small battle ensued. This instilled fear in white slaveholders, resulting in the passage of the 1740 Negro Act to further control Black individuals. This story is commemorated at the Stono Slave Rebellion at the Elliot and Rose Plantations in Ravenel, South Carolina, a site on the Network to Freedom. Source: Stono Slave Rebellion at the Elliot and Rose Plantations Network to Freedom Application.

The Christiana Riot occurs in Christiana, Pennsylvania. In the small town within Lancaster County, a group of free Black individuals and white abolitionists confronted a Federal Marshall and slave catching posse who charged themselves with capturing four freedom seekers (John Beard, Thomas Wilson, Alexander Scott, and Edward Thompson). Violence ensued, the enslaver was killed, and ultimately 38 individuals were charged with, but never convicted of, treason. This event is commemorated in the Network to Freedom at Zerchers Hotel in Christiana, Pennsylvania: a site on the Network to Freedom. Source: Zerchers Hotel Network to Freedom Application.

James Matthews published second installment of "Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave.” Published in five parts, the second installment includes the narrator's memory his experience as an enslaved man, his motivations for escape, and his capture. Source: DocSouth, “Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave.”

People from Oberlin travelled to Wellington to rescue John Price, who had been arrested by slave catchers despite his two year residence in Ohio. The Oberlin Wellington Rescue Monument is a site on the Network to Freedom. Price's burial site, Westwood Cemetery, is a site on the Network to Freedom. Source: "Oberlin-Wellington Rescue," Oberlin College News, https://www.oberlin.edu/news/oberlin-wellington-rescue, accessed September 1, 2021.

Frederick Douglass married Anna Murray in David Ruggles' home in New York. Reverend James W.C. Pennington, also former freedom seeker from Maryland, married the couple. Source: David Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (Simon and Schuster: New York, 2018), p.80-83.

Rev. Wallace Shelton of Zion Baptist Church married Henry and Louisa Piquett. They were married by at the residence of a Mrs. Blackburn. The couple were emancipated African Americans who were active on the Underground Railroad. The Henry and Louisa Piquett Burial Sites in are in the Network to Freedom. Source: Henry and Louisa Piquett Burial Site Network to Freedom Application.

After three days of fighting, Federal troops at Harpers Ferry surrendered to Confederate Major General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. The Confederate army captured “contraband,” or freedom seekers who sought refuge behind Union lines, and returned them to slavery per Confederate policy. The History of the New York 22nd State Militia details, “When the place was captured by Jackson, in September...all these poor creatures were taken from their houses, formed in a great drove, and driven South, like so many cattle, crying and wailing for their lost glimpse of freedom.” Source: George Wood Wingate, History of the 22nd Regiment of the National Guard of the State of New York: Vol 22 Part 4 (New York: E.W. Dayton, 1896), p. 84-86.

This day is recognized as the day Harriet Tubman escaped from her enslavers for the first time. Harriet left her enslavers home with her brothers, Ben and Henry. After three weeks, they made the decision to return to their enslavers on the eastern shore of Maryland. Shortly after, Harriet escaped again, this time travelling to Philadelphia. When asked about achieving her freedom years later, Tubman recalled “I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.” Source: Kate Clifford Larson, Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero (New York: Random House Publishers, 2003), p. 77-84.

Abolitionists held a meeting in Faneuil Hall in Boston, Massachusetts in response to the arrest of freedom seeker George. After his escape from Louisiana, George stowed away on the ship Ottoman to escape. After he was discovered, he tried to flee from the ships captain by commandeering a sailboat. After a heated chase over sea and land, the ships captain arrested George. In the Fanieul Hall meeting, famous abolitionists including Charles Sumner, Samuel Gridley Howe, and Wendell Phillips protested the "shameful outrage upon the sacred rights of humanity," and resolved to make a committee of vigilance. Source: Safe Harbor: The Maritime Underground Railroad in Boston.

Lewis, Harriet, and Joseph Hayden escaped from their enslavers in Kentucky. They worked with Underground Railroad operatives Calvin Fairbank and Delia Webster to cross the Ohio River, where they then travelled alone first to Canada, then to Boston, Massachusetts. There, the Haydens became community leaders in the fight for freedom and equality. The Lewis and Harriet Hayden House in Boston, Massachusetts is a site on the Network to Freedom. Source: Film, Fighting for Freedom: Lewis Hayden and the Underground Railroad

Black Seminoles, including freedom seekers to whom the community gave refuge, traveled on the Trail of Tears from Florida to Oklahoma and then sought freedom in Coahuila, Mexico. Subsequently, the Black Seminoles played a major role in defending the Texas borderlands, serving in the Seminole Negro Indian Scouts from 1870, until the U.S. Army Disbanded the scouts in 1914. Generations of Black Seminole families, including several freedom seekers and four Medal of Honor recipients, are buried in the Seminole Indian Scouts Cemetery in Brackettville, Texas, and it has become a pilgrimage site for descendants. This cemetery is a site on the Network to Freedom. Source: Ranger Roadshow Episode 5: Seminole Indian Scouts Cemetery.

Last updated: August 27, 2022