In July 2015, a group of Sigangu youth from the Rosebud Reservation stood at the edge of a battlefield overlooking the Little Bighorn River, ignoring the heat. Their attention was fully focused on their elders, who were telling them a story they had heard many times before. But this time they were standing on sacred ground. As their elders spoke of the Battle of Little Bighorn, the students were able to sense the bloodshed of their ancestors. These young people were standing in the place of Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull and hundreds of other great warriors of the Lakota and Arapaho and Northern Cheyenne. The significance of this place at that moment was not the defeat of George Armstrong Custer and his Army but rather the understanding that they were able to live today because of a stand taken by their ancestors so many years ago.

The battle was fought along the ridges, steep bluffs, and ravines of the Little Bighorn River from June 25 to 26, 1876. Today, the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument is a protected site, entrusted to the National Park Service (NPS). The location of a great conflict, the site also honors a battle of great consequence between the U.S. government and America’s native people.

The NPS is charged with considering, recording, and sharing all of America’s stories. The Battle of Little Bighorn is just one example of how the NPS can provide an opportunity to learn how Native Americans have had to take a stand for their people, culture, and lifeways over time. There are many native stories embodied within our nation, and it is critical that we include these stories as a part of our collective history.

Who Americans are as a nation is dependent upon how we remember our past. Both the NPS and teachers are positioned to help broaden our understanding of history and take steps toward inclusive storytelling. This is not always easy, especially when it comes to telling difficult truths about painful episodes in our past. Just as the Sigangu youth heard about their own history that hot summer day in Montana, so must all of America hear not only about the U.S. Army’s role in that fight but also about the deeds of the native warriors who were fighting for their people.

The challenge for the NPS, as well as teachers across America, is to incorporate all of our stories, including those of Native Americans’ past and present. To understand the layers of history in America, it is important to realize that the United States was built on the backs of the First Nations. The fact that Native American populations are still here today is testimony to the strength and resilience of a people who have taken a stand throughout history to defend their rights, way of life, and cultural identities.

As a result of the European settlement of North America, Native Americans have been forced to adapt to the shifting landscape of a new nation, bent on building a country of immigrants on an already occupied continent. During the Colonial era, Native Americans made treaties with Europeans to cement alliances, establish trade, and concede land. Once the United States became a nation, President George Washington established a relationship between the new country and the Indian Tribes. In the newly ratified U.S. Constitution’s commerce clause, Congress recognized the “inherent sovereignty” in tribal governments by naming them as equals in treaty and trade agreements.

The United States continued to sign treaties with American Indians—including agreements placing Tribal Nations on reservations—until 1871, when the House of Representatives ceased to recognize individual tribes within the country as independent nations. Since then, the government-to-government relationship has been defined by Congressional acts, Supreme Court decisions, and executive orders. In spite of the scope and sequence of federal Indian Law, many treaties and laws were abrogated or violated to the advantage of a growing United States.

Just as the warriors at Little Bighorn fought for their people and their rights as U.S. citizens, the fight continued into the twentieth century, as Native

Americans continued to battle for their sovereign rights in their relationship with the federal government. Products of those struggles include the Indian Civil Rights Act, establishing the legitimacy of Tribal Courts through adopting rules of evidence, pleading, and other requirements similar to those in state and federal courts. The creation of this law allowed Native Americans to have a fair and just system in which to fight for their rights as citizens of sovereign nations. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 and the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 came about through a grassroots effort to combat the indiscriminate removal of native children from their homes in order to place them in boarding schools and for adoption for non-native families.

The 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act ended the laws restricting American Indians’ ability to practice their ceremonial and traditional rights. In 1994, through an executive order, an amendment to this act gave Native Americans access to their sacred sites and the use and possession of sacred objects. The tribal entities had argued that rules abolishing their ability to practice their traditions and rituals violated their civil rights as U.S. citizens, as well as the rights of sovereign governments.

In interpreting and teaching the history of Native Americans, America has concentrated on the use of archaeology and ethnography to tell their stories. In 1916, the NPS was founded, based on romanticized perceptions of the West and Native Americans as depicted by artists such as George Catlin, James Fenimore Cooper, and Thomas Cole. Early archaeologists and anthropologists from the Bureau of American Ethnology went out West seeking to document the ruins of what they believed were dying American Indian cultures. The anthropologists sent sacred objects, human remains, and cultural items back to the Smithsonian Institution, drawing conclusions about Native Americans—without ever consulting those whose history they were “creating.”

In the 1990 Native American Graves and Repatriation Act, Native Americans took a stand against appropriating cultural materials, as well as allowing them to recover sacred items, human remains, and cultural objects taken by anthropologists and archaeologists. This act requires that all institutions receiving federal funding must make an inventory of their collections and publish it, so that Tribal Nations can determine whether they should claim repatriation.

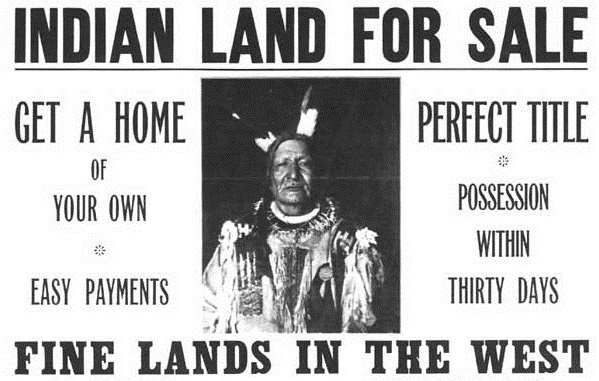

Throughout modern history, Native Americans have often been forgotten or misrepresented by American culture. American culture still correlates Native American identity with stereotypes, and Hollywood movies continue to define what Native America is even today. Hollywood has utilized typecasts such as the “vanishing Indian” or the “noble savage.” The “vanishing Indian” stereotype is at the core of America’s frontier myth, which posits that Native Americans are noble and brave but they are destined to sacrifice both freedom and land for the making of America.

In reality, Native Americans are living, working, and practicing their culture in all parts of American society, not just some long-forgotten warrior epics. Many films, movies, books, and classroom activities available to educators have been produced by Native Americans, and these give an accurate portrayal of Native American history and contemporary life. The NPS also provides a variety of resources to help teachers bring Native American stories into the classroom. Together, the NPS and educators can bring the true history of Native Americans and their contributions to the United States to life for students.

American Indians have never ceased to believe that someday their voices would be heard. They have invested in maintaining their history through storytelling, oral traditions, and documentation. Native Nations run their own museums, in which they tell their creation stories and tribal histories, and also highlight how their people have survived and how they live today. Traditional activities, some public and some private and sacred, are still maintained as part of the rich heritage of American Indians because of the stand they have taken throughout American history.

The NPS and teachers are in a unique position to embrace native history by listening to native people and by giving voice to them in the course of classroom teaching. Educators are encouraged to use Native American educational materials and to visit www.nps.gov to find resources to help students understand how Native Americans have taken a stand to keep their stories and cultures alive.

American Indians are an integral part of the history of the NPS, and each and every park has a story to tell about the native culture that exists inside its boundaries—a great resource for teachers. For example, Great Smoky Mountains National Park in eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina sits on the ancestral homeland of the Cherokee Indians. When Great Smoky was established, the neighboring Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians proved vital to the park’s success.

In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps-Indian Division, made up of men from the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, helped to build many of the roads, trails, and buildings, some of which continue to be used today. Today, the Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) at the Eastern Band works with the NPS to tell the stories of sacred spaces within the park boundaries, such as Clingman’s Dome, known as Kuwahi to the Cherokee.

Everglades National Park exists alongside its neighbor, the Miccosukee branch of Seminole Indians. Everglades National Park employed a Civilian Conservation Corps - Indian Division, made up of Seminoles who helped to clear the land for the town of Everglades and worked as firefighters during times of drought.

Recently, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park joined a group of national parks whose enabling legislation tasks them with telling the stories of North American indigenous peoples both past and present. Hopewell Culture educates the public about the day-to-day lives, contributions, perceived values, and interactions of the Hopewell peoples. Other parks with similar missions include Mesa Verde National Park, which interprets the Ancestral Pueblo People; Canyon De Chelly National Monument; Casa Grande Ruins National Monument; Montezuma Castle National Monument; Navajo National Monument; and many more.

It is incumbent upon the NPS and all educators, both formal and informal, to reach out and seek insights and histories that will help America understand the struggles of our native people and the stands they have taken to maintain their culture, lifeways, and human rights thoughout history.

New York Historical Association

Teaching About Native Americans

• The Hopi Tribe’s living traditions and early American archeology on Hopi land are the subjects of the National Park Service lesson plan, Enduring Awatovi: Uncovering Hopi Life and Work on the Mesa.• During the American Revolution, New York’s Mohawk Valley became the setting for a fierce battle that pitted residents of the area, including the nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, against each other. Teach this story with the National Park Service lesson plan, The Battle of Oriskany: Blood Shed a Stream Running Down.

• Teach the complexity of American Indian politics and resistance with the lesson The Battle of Horseshoe Bend: Collision of Cultures, about a faction of Creek Indians who fought Americans, Creek, and Cherokee along the Tallapoosa River, Alabama, in 1814.

• The Trail of Tears and the Forced Relocation of the Cherokee Nation. lesson plan from the National Park Service guides students to explore the causes and consequences of the violent migration West.

• Civil War history units can integrate American Indian history with the National Park Service lesson plan, Battle of Honey Springs: The Civil War Comes to Indian Territory.

• The National Park Service has partnered with the University of Oregon to create a more culturally sensitive curriculum that reflects the mission to allow Native Peoples to tell their own stories. Find it at HonoringTribalLegacies.com.

• Planning a field trip? The Places Reflecting America’s Diverse Cultures Travel Itinerary from the National Park Service offers information about American Indian cultural sites throughout the United States.

McBryant, Carol, Mattea Sanders, and Carolyn Fiscus. "Teaching the Truth About Native America" In National History Day 2017: Taking a Stand in History, edited by Lynne O'Hara, 38-41. 2017.

Last updated: June 3, 2021