NPS photo.

Introduction

During the middle Cretaceous, around 100 million years ago, North America was near its current location, but it would have looked much different. Where today we would see the Midwest, 100 million years ago there was a shallow sea from the Arctic to the Gulf of America. There are several reasons for this. First, North America was much lower in elevation at this time. The Rocky Mountains would not be pushed up until the end of the Cretaceous, so the entire midsection of the continent was much closer to sea level. Second, there were no extensive ice caps to trap water, so sea level was higher. However, these two factors together wouldn’t be enough to submerge the interior of the continent. A third factor makes up the difference: the world’s ocean basins were shallower. Most of the oceanic crust at this time was young, warm, and relatively buoyant, having been formed at a rapid pace as plates “rushed” apart with the breakup of the supercontinent Pangea. What happened next is simple: If you raise the floor of a basin but don’t change the amount of water, the water has to go somewhere, in this case onto the shallow parts of the continents.

Western Interior Seaway

Open Source photo from Sampson, Scott D. et al (New Horned Dinosaurs from Utah Provide Evidence for Intracontinental Dinosaur Endemism)

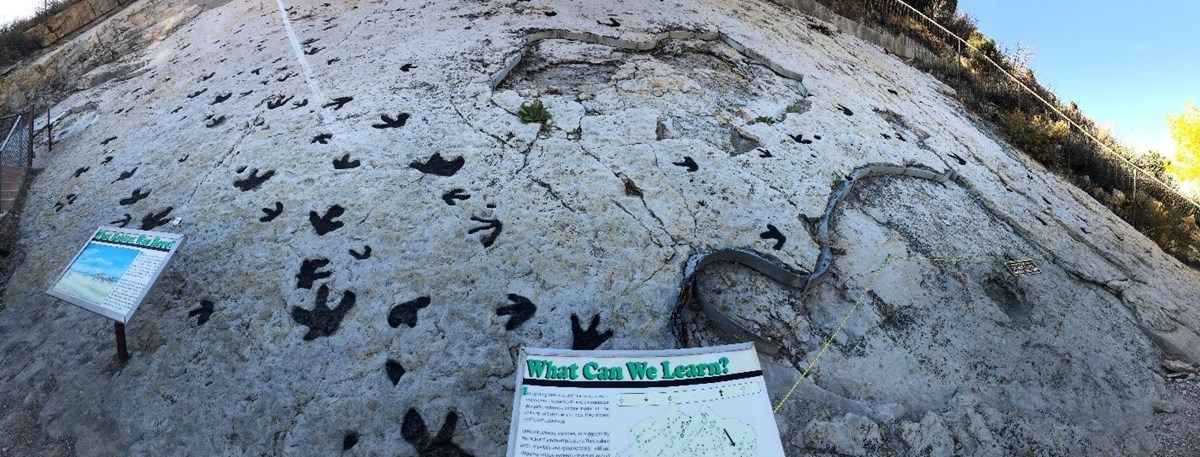

Eventually the shallow sea in North America (the “Western Interior Seaway”) would spread as far west as central Utah, but about 100 million years ago it was only as far west as roughly the Front Range of Colorado. Where today there are mountains, there was then a coastal plain leading to the seashore. From Colorado to New Mexico, the coastal strip sediment was trampled by dinosaurs. Was this because it offered a convenient north–south route that could be easily followed? Were they migrating herds, as some scientists have suggested from places where trackways appear to be parallel? Or were dinosaurs just very abundant and only this track-bearing area was preserved at this time? Behavior doesn’t fossilize well, and rock preservation and exposure are inconvenient—it’s hard to be certain!

The Track Makers

The majority of trackways were made by large herbivorous dinosaurs that usually walked on two legs (occasionally dropping onto all four) and had three toes per foot. They probably looked something like Iguanodon from slightly older rocks in Europe. A similar dinosaur, Eolambia, lived in Utah at about this time. Smaller three-toed tracks were probably made by small theropod dinosaurs. This was close to the time of Deinonychus, but Deinonychus and other dromaeosaurs would have left two-toed tracks, so these trackmakers would be something else, perhaps more like the ornithomimids or “ostrich-mimics”. Other, rarer, tracks were made by large theropods (perhaps something like the slightly older Acrocanthosaurus), ankylosaurs, pterosaurs, and crocodile relatives.

Visiting the Trackways

NPS photo.

There are multiple trackway sites with as many as hundreds of tracks. Two of these sites are within National Natural Landmarks, both in Colorado: Dinosaur Ridge in the Morrison-Golden Fossil Area (Colorado), and Roxborough State Park (Colorado). Clayton Lake State Park (New Mexico) is another protected area with many tracks.

Site Index and Credits

Age of Dinosaurs (2021)

Text by Justin Tweet (AGI). Contributors: Vincent Santucci (GRD), Adam Marsh (PEFO), ReBecca Hunt-Foster (DINO), Don Corrick (BIBE). Project Lead / Web Development, Jim Wood (GRD).

References

-

Tweet, J.S. and V.L. Santucci. 2018. An Inventory of Non-Avian Dinosaurs from National Park Service Areas. in Lucas, S.G. and Sullivan, R.M., (eds.), Fossil Record 6. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 79: 703-730. https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2257153

-

Santucci, V.L., A. Marsh, W. Parker, D. Chure, and D. Corrick, 2018. “Age of Reptiles”: Uncovering the Mesozoic Fossil Record in three Intermountain national parks. IMR Crossroads. Spring 2018, p. 4-11. https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2253529

Last updated: February 27, 2025