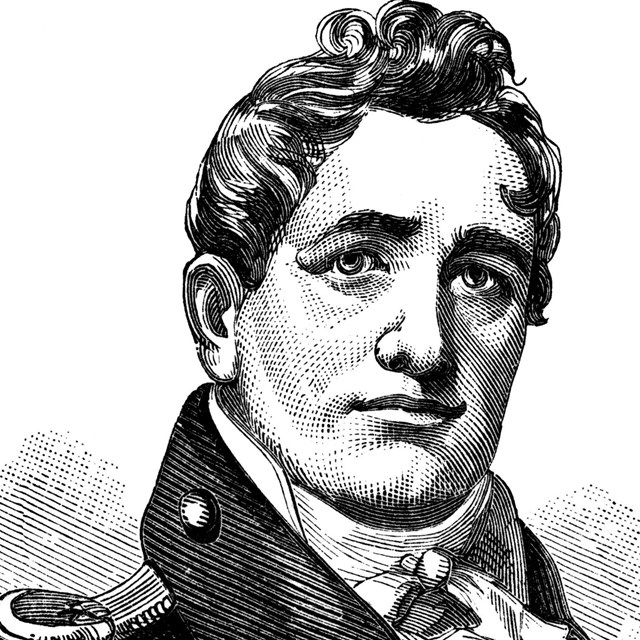

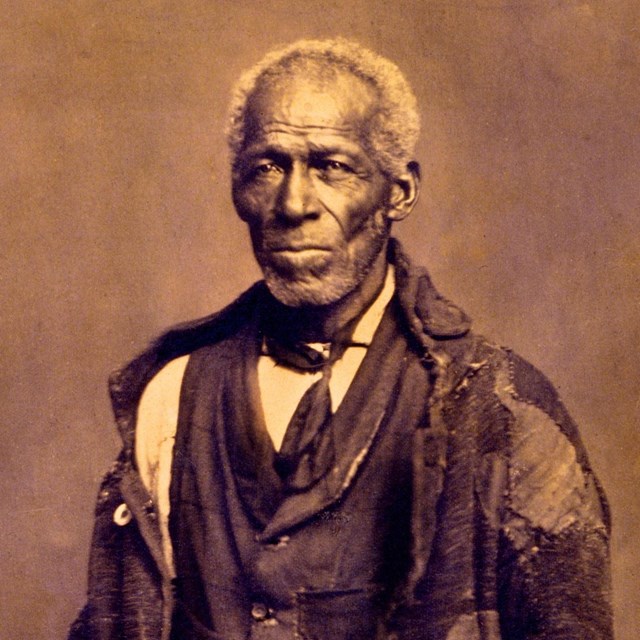

The young United States, with its tiny navy of frigates, had one sea-bound advantage—its growing fleet of privately owned vessels sent out with government licenses called "Letters of Marque." Authorized to carry guns, the ships preyed on defenseless British carriers. It was a lucrative business, although captured prizes were subject to the customary import taxes. The U.S. government issued 1,100 commissions to privateers between 1812 and 1815. The self-styled marauders were a serious annoyance for British commerce and drove up insurance rates. Merchants demanded government protection. Cruising around shipping lanes in the West Indies, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and near the British Isles, American privateers forced many British carriers to sail in armed convoys. Baltimore had a leg up on the rest of the maritime community. In their search for speed under sail, local ship builders and owners had developed a topsail schooner known as the Baltimore clipper. Heavy with sail, they were the majestic, sleekly designed thoroughbreds of their day. Clippers were known to taunt their competition by flying pennants with slogans like “catch me if you can.” Baltimore privateers garnered122 letters of marque from the U.S. government. After a British blockade closed in on the Chesapeake and American warships were trapped or closed out, swift-sailing clippers were still able to occasionally slip out to sea, especially when the weather and visibility were poor. As early as 1812, legendary skipper Joshua Barney, commanding the clipper Rossie, set a high standard by capturing 18 British prizes valued at $1,500,000. In 1814, Thomas Boyle, at the helm of the Chasseur, displayed Baltimore’s own brand of bravado by proclaiming a mock one-ship blockade of the entire British Isles. After defeating H.M. schooner St. Lawrence near Cuba in early 1815, Boyle returned to his home port in triumph, winning the title “Pride of Baltimore” for his plucky vessel. The Pride of Baltimore II, a modern-day reproduction of a Baltimore Clipper, serves as a world ambassador for Baltimore and is named for Boyle’s famous privateer. excerpt from "In Full Glory Reflected: Discovering the War of 1812 in the Chesapeake" by Ralph E. Eshelman and Burton K. Kummerow Black PrivateersMany Black men were privateers tool; it is estimated that as many as 20 percent of privateer crews were African American. Serving as a possible alternative to serving the American military, there was no law stating that Black men could not be sailors. However, how Black privateers were treated is still up for debate. Some historians contend that, to Americans, the war against Britain was a bigger issue than race at the time and, as a result, Black and white privateers were treated about the same.

|

Last updated: August 8, 2023