|

After crushing the Americans at Bladensburg and invading the nation’s capital, the British targeted Baltimore. If they could capture the city---the third largest in the United States and a commercial and shipbuilding hub---they could likely bring the war to an end. Military and civilians, including free and enslaved African Americans, rallied to fend off the British. On September 12-14, 1814, the British attacked by land from North Point and by water at Fort McHenry on the Patapsco River. The impressive American defenses and the failure to capture Fort McHenry persuaded the British to withdraw, essentially ending the Chesapeake Campaign of 1814. Learn about some of regional War of 1812-related locations below. Baltimore

Battle MonumentBaltimore successfully resisted the British assault in September 1814, thanks to thousands of determined volunteer citizen-soldiers. The following year a grateful city laid the cornerstone for the Battle Monument in downtown Baltimore, the first War of 1812 memorial in the nation. Designed by J. Maximilian M. Godefroy, the 39-foot monument, with an unusual mix of Egyptian and Classical designs, recognizes the common soldier and features names those who fell in battle--regardless of their rank-- during the Battles of Baltimore and North Point. “Lady Baltimore,” a classical female figure, tops the monument. The City of Baltimore features the monument on their official Seal. Bellona Gunpowder Company

Bellona Gunpowder Company mills, operating from 1801 to 1856, was located in present-day Lake Roland Park along the banks of the Jones Falls. Bellona was one of several Baltimore powder mills and produced explosives used in the defense of Baltimore. At its peak it produced one-fifth of all the U.S. powder. Gunpowder—a mixture of saltpeter, charcoal, and sulfur—fueled all explosive weapons. Fells Point Historic DistrictBaltimore’s importance as the commercial heart of the Chesapeake region wasn’t the only reason the British wanted to capture the city in 1814. They also wanted to stifle Fell’s Point---the home port for many of the privateers that preyed on British merchant ships. The United States augmented its small navy by licensing privately owned ships to attack enemy vessels. Baltimore privateers captured more than 500 British ships during the War of 1812. Fort Babcock, Fort Covington, and Ferry Point

Three gun batteries hugging the upper shore of Ferry Branch guarded the west flank of Fort McHenry. They included the makeshift earthworks of Fort Babcock, the incomplete Fort Covington, and a temporary redoubt at Ferry Point. During the bombardment of Fort McHenry on September 13–14, 1814, these Ferry Branch fortifications stopped a surprise British maneuver to attack Fort McHenry from the less well-defended rear. This close call exposed Fort McHenry’s vulnerability to a flanking attack. The fortifications were strengthened and a defensive boom added across Ferry Branch in case the enemy returned.

Fort McHenryBritish ships launched an attack on Fort McHenry early on September 13, 1814. The fort defended the water approach to the city of Baltimore. The future of the city and possibly the United States depended on the outcome. After the American defeat at Bladensburg, and the British capture and partial burning of Washington, D.C. a loss here would be devastating. Fort Wood

Known as Lookout Hill, high ground near Fort McHenry served as observation post, military camp, and gun battery. Although unfinished when the British arrived, the battery helped fend off a naval flanking attack September 14, 1814. Had the enemy maneuver succeeded, they could have penetrated the city’s western defenses. The circular battery was later named Fort Wood for an officer killed on the Niagara River. Indian Queen Tavern

After 10 harrowing days aboard ship and witnessing the British bombardment of Fort McHenry, Francis Scott Key spent his first night ashore at the Indian Queen Tavern, September 16-17, 1814. The inn operated until the 1830s. Moved by what he had experienced two days earlier, Key used his time here to complete four stanzas for what would become American’s national anthem. The site is now Hopkins Plaza in Baltimore City.

Hampstead HillGin Riots

(c) Gerry Embleton Rodgers Bastion

After the stinging defeat at Bladensburg and invasion of Washington, Americans rallied to save Baltimore. All available able-bodied men were called to build defenses. Black and white, enslaved and free, united to dig earthworks across Hampstead Hill and adjacent heights. British land forces approaching on September 13, 1814, stopped at the sight of the well-armed defenses. Deciding that storming the American stronghold would be too costly, the British army retreated. Credit for the defenses goes to Major General Samuel Smith and Commodore John Rodgers. Smith coordinated the overall effort; Rodgers commanded Hampstead Hill.

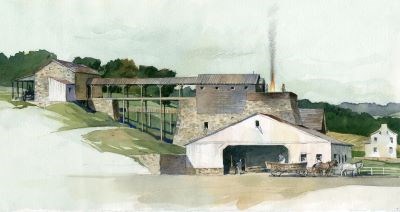

Northampton Iron Furnace

Northampton Iron Furnace, operating from 1761 to about 1830, played a significant role in the War of 1812. Part of the prosperous Hampton estate, the foundry’s workforce was made up primarily of enslaved African Americans who produced iron, cannons, shot, and camp equipment for the war effort. Charles Carnan Ridgely, ironmaster and owner of the estate, also contributed funds and other supplies for Baltimore’s defense in 1814.

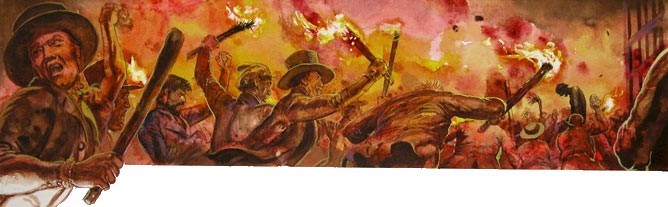

Offices of the Federal Republican

Incited by anti-war editorials in the Federal Republican, an angry mob destroyed the newspaper’s Gay Street office in June 1812. Rioters returned when editor Alexander Contee Hanson resumed publication from the Charles Street site on July 27. Hanson and about 25 supporters were escorted to jail for protection. “A scene of horror and murder ensued” as the mob stormed the jail, killing or wounded the occupants. Never fully recovered from mob-related injuries, Alexander Contee Hanson remained an outspoken war opponent. He served in the U.S. House and then the Senate from 1813 until his death at age 33 in 1819.

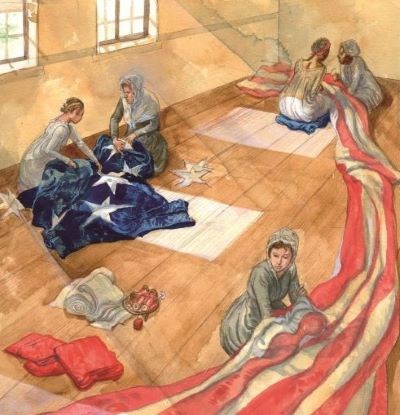

Star-Spangled Banner Flag HouseIn 1813 Mary Pickersgill’s flag-making business was commissioned to sew a garrison flag and a smaller storm flag for Fort McHenry. Mary’s mother, daughter, nieces, and African American indentured and enslaved servants helped complete the task in about seven weeks. Too large for her house, the 30 x 42-foot garrison flag was finished on the floor of a nearby brewery. Mary’s helpers included an African American indentured servant named Grace Wisher. Stodder’s ShipyardThe mouth of Harris Creek was once part of Baltimore’s thriving maritime industry. David Stodder began building ships here in the 1780s. The first U.S. Navy frigate, Constellation, launched from Stodder’s Shipyard in 1797 and played an active role in the War of 1812. Although a British blockade kept it from sea, its cannons and crew protected Norfolk and Portsmouth harbors.

Wells and McComas Monument

Daniel Wells, 19, and Henry McComas, 18, made history September 12, 1814, when they allegedly killed British commander Major General Robert Ross. The two sharpshooters fired simultaneously. Both were quickly shot dead by British soldiers. Considered heroes, Wells and McComas were buried together and exhumed twice before finally being laid to rest with great fanfare in 1858. A funeral song and dramatic play commemorated the reburial. Westminster HallOnce Baltimore’s most prestigious cemetery, Westminster Burying Ground was the final resting place for many prominent Baltimoreans, including some 25 from the War of 1812. Notable burials include: General Samuel Smith, commander of American forces in Baltimore; General John Stricker, American commander at North Point; and John Stuart Skinner, U.S. prisoner exchange agent. David Poe, Sr., who served at the Battle of North Point, is also buried here. He was the grandfather of writer Edgar Allan Poe. North Point

Aquila Randall monument

Aquila Randall, a 24-year-old member of the Mechanical Volunteers, 5th Regiment of the Maryland Militia, was a casualty in a skirmish preceding the Battle of North Point on Sept. 12, 1814. While 21 other Americans and British Major Robert Ross died in this skirmish, Randall was the only member of his uint killed. In memory, the First Mechancia Volunteers erected the the Aquila Randall Monument in July 1817. It is the second oldest known military monument in Maryland, the third in the U.S.

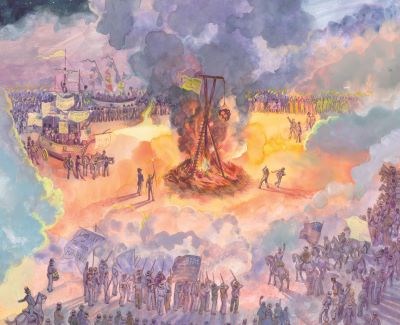

Battle Acre

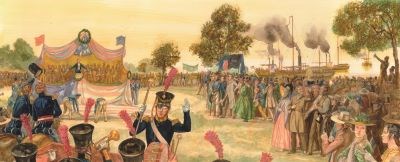

The excitement was palpable as crowds gathered at Battle Acre on September 12, 1839, to mark the 25th anniversary of the Battle of North Point. Officials laid the cornerstone for a memorial to the citizens-soldiers who defended Baltimore against British attack in 1814. The original Star-Spangled Banner was spread across the stage at the event. Bear Creek

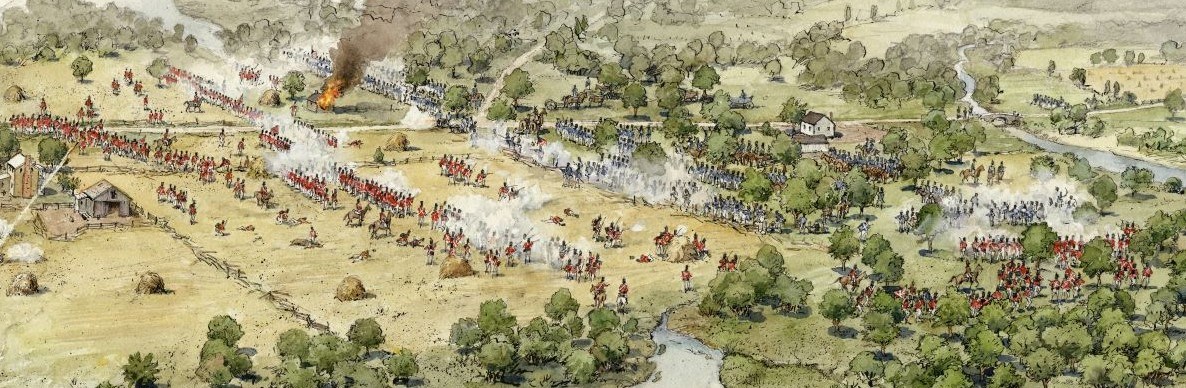

The narrow land shaped by Bear Creek, Bread and Cheese Creek, and Back River was the site of the Battle of North Point, September 12, 1814. Some 3,200 Americans clashed with 4,500 British to delay the advance on Baltimore.

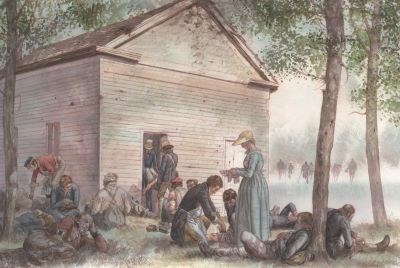

Methodist Meeting House

The Methodist Meeting House that stood near the North Point battlefield saw action September 11-12, 1814. Brigadier General John Stricker camped 3,200 troops here to await the enemy’s advance. When the Americans withdrew, British soldiers camped on the same grounds. The church became a field hospital for both armies. American and British physicians worked side by side to treat soldiers wounded in the battle.

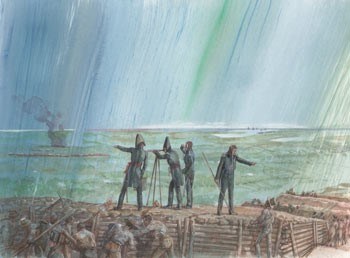

Ridgely House

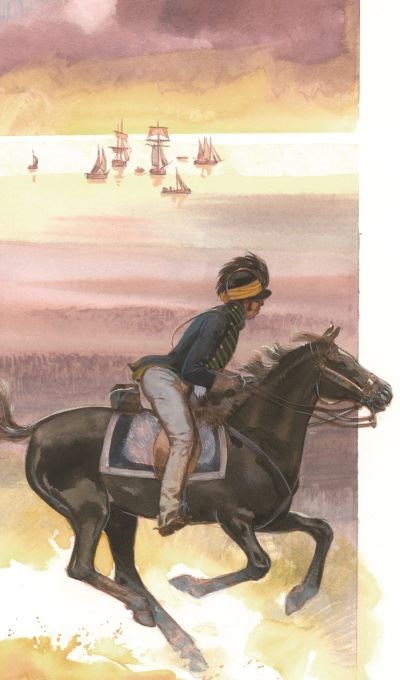

The cupola atop the Ridgely house served as a lookout station in 1813 and 1814 and was operated by Major Josiah Green. The 1767 farmhouse was part of an intricate early warning system that included schooners and gunboats, shore stations, and horse relays. The stations communicated with flags by day and lanterns by night.

Todd House

Private Bernard Todd paid dearly for having his home used for military purposes. When the British threatened Baltimore in 1813, it was headquarters for American troops who guarded the Patapsco Neck. Todd’s property also served as a signal house and horse courier station. Three mounted sentries stationed here on September 11, 1814, hurried to announce that the British had arrived. In retaliation, enemy soldiers torched the house on the return march to their ships. |

Last updated: September 6, 2020