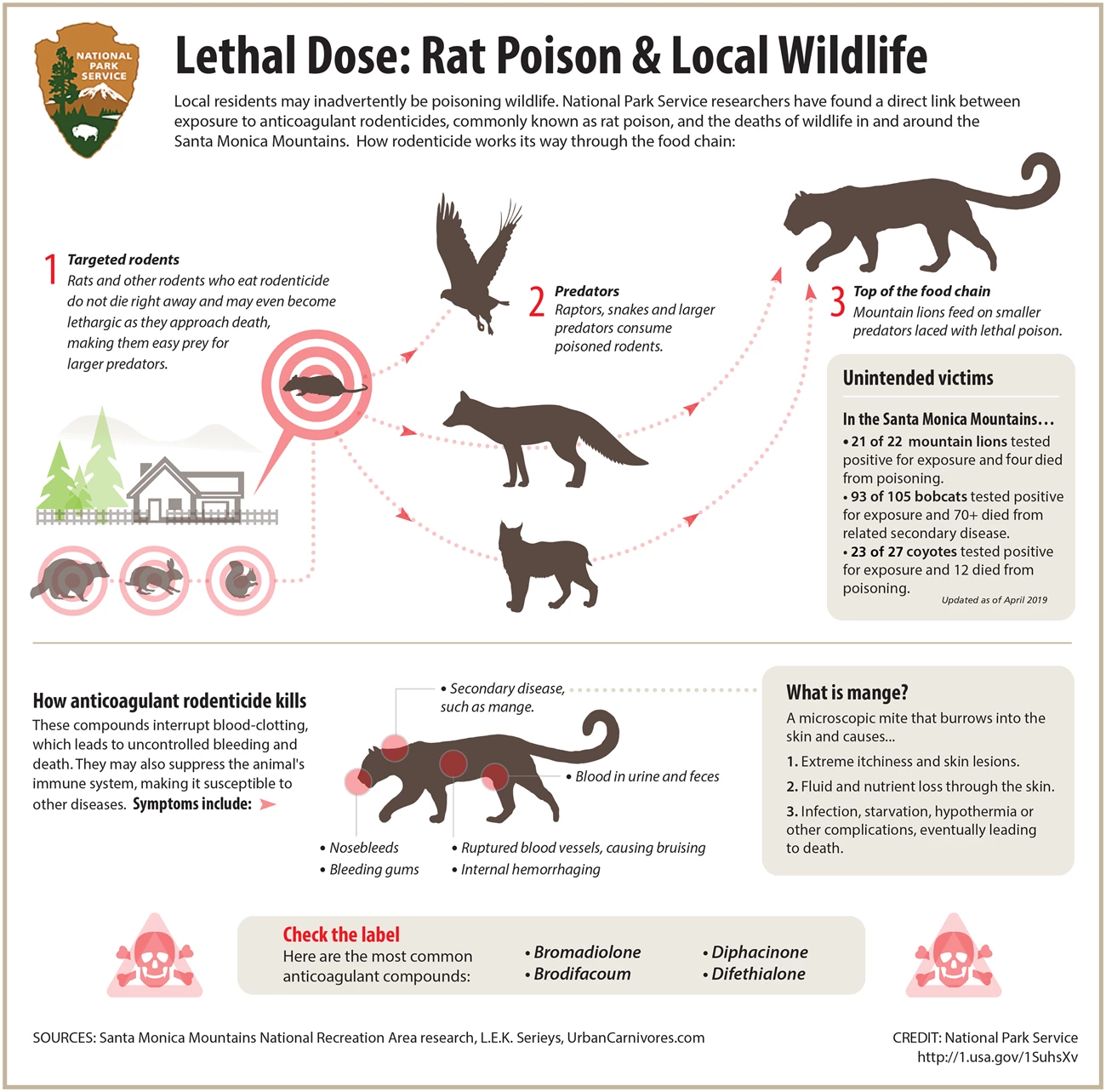

National Park Service The use of anticoagulant rodenticide poison to control rodents in your yard, neighborhood and community can result in exposing your pets and local wildlife to this deadly poison. Regardless of who distributes the poison -- homeowners, professionals, or your HOA -- your pets and local wildlife are at risk of exposure. Death from anticoagulant rodenticide poisoning takes longer than you might think. Rodents that consume anticoagulant poisons do not die immediately. The poison is designed to block the vitamin K cycle which is important in clotting the body’s blood, often resulting in a slow death. It can take up to 10 days for the rodent to die by internal bleeding, if it is not eaten by another animal first. Rodents filled with toxic anticoagulant rodenticide poisons continue to move around in the environment and as they start to feel the effects of the poison they begin to move slower and become easy targets for your cat, dog and our native predators such as bobcats, hawks, owls, coyotes etc. Research has shown that anticoagulant poison moves up the food chain and eating a poisoned animal can lead to secondary poisoning of dogs, cats and many wild animals. How are pets and wildlife getting poisoned? Unintentional Poisoning Non-target species are poisoned through primary, secondary and tertiary poisoning. Primary Poisoning of non-target animals may occur when a bird eats the pellets broadcasted on the landscape or pellets that fall out of the bait box. Domestic dogs have been poisoned when they eat bait from boxes or get into unsecured packaging in their homes. Secondary Poisoning of non-target species occurs when predatory animals eat poisoned animals, therefore ingesting the poisons secondarily. For example, a bobcat eats a poisoned gopher, exposing the bobcat to the poison, creating a secondary exposure to the poison. Your cat could be at risk too. If your cat ventures outside it will likely catch or try to catch a small mammal, if that mouse, rat, squirrel or rabbit has eating poison your cat is at risk of secondary poisoning. Tertiary Poisoning of non-target species occurs when a predatory animal eats another predatory animal that has been secondarily poisoned. For example, a mountain lion eats a coyote with secondary poisoning that ate a poisoned squirrel. Anticoagulants move through the food chain. Research discovers rodent poisons move up the food chain. Wildlife affected in our local Southern California neighborhoods: Scientific research on local wildlife in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreational Area and surrounding fragmented habitats has detected startling evidence on how many of our native carnivores are exposed to anticoagulant rodenticide poisons. This research has shown that secondary poisoning from anticoagulant rodenticides is a wide spread problem throughout our local landscape. Testing results from the 3 carnivore species (bobcats, coyotes and mountain lions) monitored in this study found that most of the animals in the study were exposed to anticoagulant rodenticides. Results from tested bobcats, coyotes and mountain lions, and exposure to anticoagulant rodenticides during NPS study: Bobcats - 92% of bobcats exposed to anticoagulant poisons. Coyotes - 83% of coyotes were exposed to anticoagulants and it was the 2nd leading cause of death during study. Mountain Lions - 94% of mountain lions were exposed to anticoagulant poisons, including a 3 month old kitten. How you can help Take Action Against Anticoagulant Rodenticides Further Reading

Open Transcript Open Descriptive Transcript TranscriptOur parks are pretty special places. Keeping them special means being good neighbors and taking care of our wildlife in the park and at home. When we use household rat poisons, we stop being good neighbors and put our wildlife at risk. It's a big problem in our parks, causing illness and often death. Rat poison is a slow killer. Poisoned rodents are easy prey for larger animals. And can pass the poison all the way up the food chain. It can also be an unintentional killer at home. So what can you do? Rodent proof your home and make it hard for them to find shelter. And get rid of anything that could be an easy source of food.

Our wildlife makes our parks special, so let's be good neighbors and keep them safe. To learn more, talk to a park ranger or visit us online at www.nps.gov/samo.

Descriptive TranscriptThis animated video opens with two characters and their dog, Nacho, exploring a vibrant park. The narrator highlights the importance of being good neighbors to our local wildlife, both in parks and at home. The scene transitions to an animated suburban neighborhood, where Nacho plays in a backyard. Inside a house, viewers see common entry points for rodents, including cracks in walls, cluttered spaces, and uncovered trash bins. Animations then illustrate the dangers of rat poison to wildlife. A sequence shows a rodent consuming poison, weakening, and being eaten by a hawk—symbolizing how the poison moves up the food chain. The visuals remain educational while avoiding graphic content. The video offers safe, practical alternatives: sealing entry points with steel mesh, decluttering to remove shelter, securing food in airtight containers, and using poison-free traps, shown in action. In the final scene, Nacho and his owners are back in the park, enjoying nature. A park ranger appears, reinforcing the message of protecting wildlife and encouraging viewers to learn more. The video concludes with the URL www. nps.gov/samo displayed on-screen.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Rodents are an issue for many homeowners but using poisons can harm local wildlife and even one's pets. Follow these two people and their dog, Nacho, as they learn safer ways to get rid of rodents. |

Last updated: May 10, 2019