Last updated: November 24, 2023

Place

Sunnyside: A Mexican American Neighborhood in Michigan before, during and after WWII

Courtesy of the Historic American Landscape Survey

Migrant Workers in Michigan

Immigrants from southern Texas began to settle in Michigan in the early 20th century. In the 1920s, the Continental Sugar Company in Blissfield, Michigan, recruited Mexicans and Mexican American laborers from Texas. Laborers worked short-term summer contracts in the sugar beet fields in Lenawee County. At the end of the summer, these workers returned home. In the 1930s, these migrant workers began to stay year-round in Michigan due to the Great Depression. Wages declined, and workers often did not have enough money to return south at the end of the season. Continental Sugar also persuaded workers to stay year-round by not charging rent during the winter for the shacks that their employees lived in. Midwestern sugar companies preferred these nonunionized Mexican and Mexican American workers to avoid dealing with labor unions.

Migrant Workers Turn to WWII Defense Work

After the outbreak of World War II in 1941, defense plants in nearby Adrian, Michigan, began hiring Mexican workers. With government contracts bringing projects to the defense plants, the factories needed to hire more workers. Magnesium Fabricators, who made parts for airplanes, was the first factory in Adrian to hire Mexican Americans in 1940. Workers preferred working in a defense plant to working in the fields. The pay was better, and the work lasted year-round. The sugar beet industry was the initial draw for Mexicans and Mexican Americans, but the defense industry allowed them to settle permanently in the Adrian area.

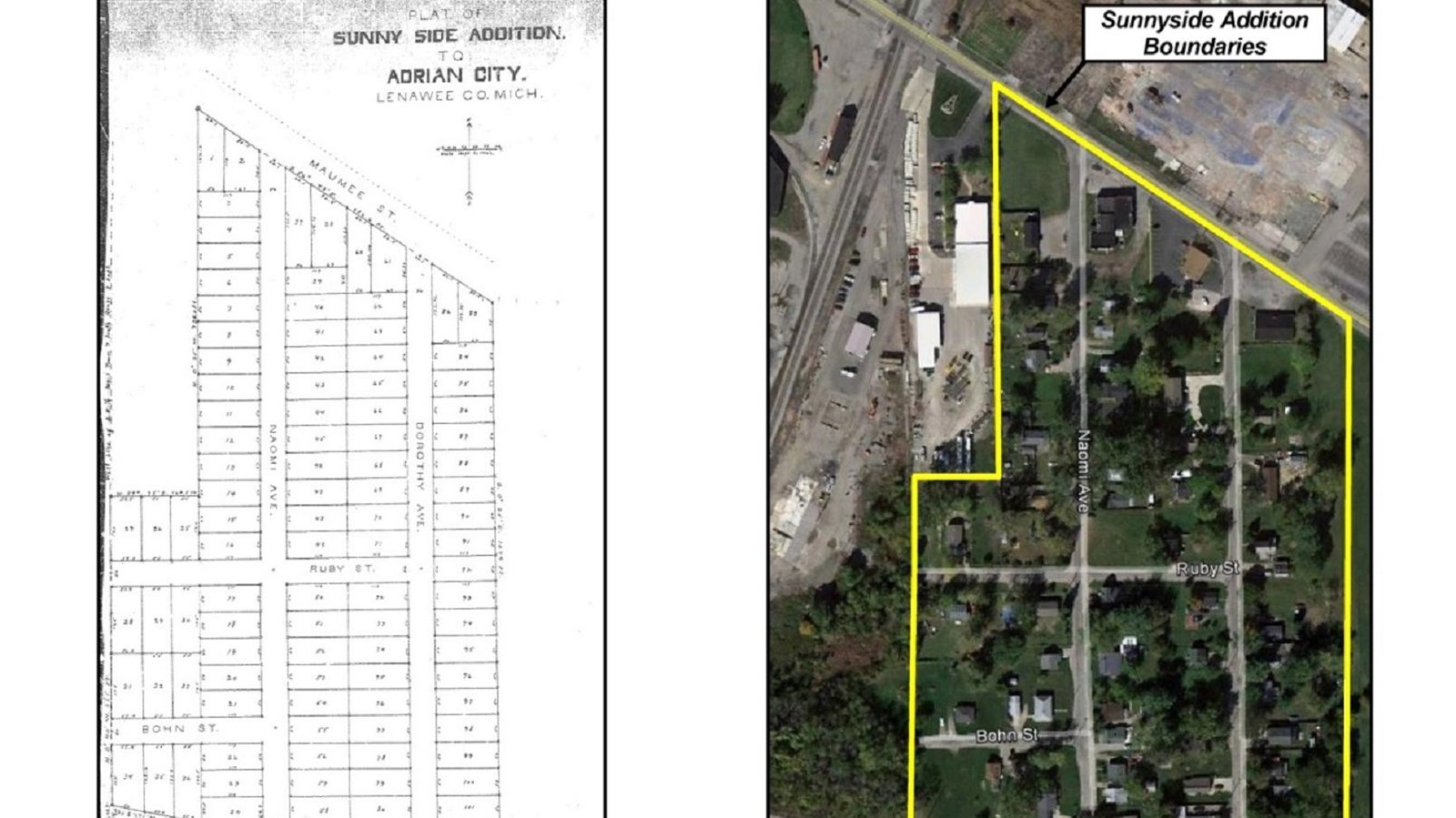

Sunnyside Neighborhood Emerges

With the shift from sugar beet farming in Blissfield to defense work in Adrian, many Mexican Americans moved to Adrian. At first, they lived in the nearby Lenawee County Fairgrounds. The living situations there were appalling, though, and residents sought permanent housing elsewhere. This group formed their own community in a neighborhood they called “Sunnyside” that had cheap rent and low property value. It was also within walking distance of the defense plants. This grouping was not by choice—land owners refused to sell land to Latinos within the city limits. After the war, some Mexican Americans returned to Texas, but many chose to stay and settle in Sunnyside. Residents opened a bakery, a taqueria, and other shops selling Mexican goods. By 1950, half the residents of Sunnyside had Hispanic surnames.

The Bracero Program and Farm Worker Activism

During the war, the United States suffered an acute agricultural labor crisis. To combat this, the United States recruited laborers from Mexico through the Bracero Program. Similar to Blissfield's labor force from Texas, “Braceros” worked short term contracts in the United States. Organizing farm workers to strike for better conditions was nearly impossible during this time. If workers attempted to unionize, companies could use Braceros to replace workers on strike. Between 1942 and 1964, more than four million Braceros worked in the United States.

With the end of the Bracero Program in 1964, farm workers in the United States ramped up their efforts to secure better working conditions and treatment from employers. Leaders like César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, and Larry Itliong organized workers and formed strikes. Their efforts helped unionize farm workers and to pass the 1975 California's Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975. This was the first law in the United States that recognized farm workers' collective bargaining rights.

Adrian’s Latino laborers joined the campaign to bring better working conditions to farm laborers. Adrian Friends of the Farm Workers (AFFW) supported the United Farm Workers Union and César Chávez’s larger national movement. Chávez visited Adrian several times during the 1970s to encourage the boycott of the sale of products from the non-unionized labor force.

Sunnyside in the Postwar Era

During the postwar economic boom of the 1950s, Sunnyside remained economically depressed. This was partially due to a lack of city services. Many residents had no indoor running water and relied on outhouses. In 1962, dysentery broke out in Sunnyside. Residents had attempted before to link Sunnyside with the city’s sewer system, but their petitions were unsuccessful. In the 1970s, there was another public health crisis. A nearby factory, Anderson Development Company, produced a potentially carcinogenic chemical called Curene 442. Testing revealed a high concentration of the chemical around the factory—and in abutting Sunnyside. Local, state, and federal agencies oversaw the cleanup of Sunnyside. Wells had to be removed, and the neighborhood was finally connected to the city’s water system. Cleanup was completed in 1993.

In 2012, Sunnyside was surveyed by the Historic American Landscape Survey (HALS) for the 2012 HALS Challenge: Documenting the American Latino Landscape. HALS surveys provide us with written histories, measured drawings, and photos of landscapes in the United States. These documents allow a landscape’s history to be preserved even if the site is changed or destroyed. Sunnyside is still predominantly a Mexican American community. Some families who moved there during World War II are still located in the neighborhood, generations later. Sunnyside is located within MotorCities National Heritage Area.

Bibliography

César E. Chávez National Monument. “History & Culture.” National Park Service. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/cech/learn/historyculture/index.htm.

César E. Chávez National Monument. “A New Era of Farmworker Organizing.” The Road to Sacramento: Marching for Justice in the Fields. National Park Service. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/new-era-of-farm-worker-organizing.htm.

Chidester, Robert, Maura Johnson, Jennifer Ross, and Ryan Schumaker of the Mannik & Smith Group, Inc., "Sunnyside Addition." Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Landscapes Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2012. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HALS No. MI-5; https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/mi/mi0700/mi0735/data/mi0735data.pdf accessed August 2022).

Lenawee Historical Society. “Migrant Farm Worker's Strike.” Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.lenaweehistoricalsociety.org/migrant-farm-workers-strike/.

Library of Congress. “A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States: 1942: Bracero Program.” Research Guides. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/bracero-program.

Rosenbaum, Rene P. “Migration and Integration of Latinos into Rural Midwestern Communities: The Case of 'Mexicans' in Adrian, Michigan.” JSRI Research Report, no. 19. The Julian Samora Research Institute, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, 1996. https://jsri.msu.edu/upload/research-reports/rr19.pdf.

Valdes, Dennis Nodín. “Divergent Roots, Common Destinies? Latino Work and Settlement in Michigan.” Julian Samora Research Institute. Michigan State University, May 1992. https://jsri.msu.edu/upload/occasional-papers/oc04.pdf.

Wessel, Bob. “Bob Wessel: Lenawee County Manufacturers Helped Bring Victory in World War II.” The Daily Telegram, July 27, 2021. https://www.lenconnect.com/story/news/history/2021/07/27/lenawee-county-manufacturers-helped-bring-victory-world-war-ii/8089051002/.

The content for this article was written and researched by Hannah Haack, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education and Park History Program.