Last updated: July 24, 2024

Person

Marie Ferribee Watkins

Brooklyn Daily Eagle Newspaper

Marie Ferribee Watkins was 92 years old when she was interviewed by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. In the 1949 article, “Important Thing: To Live Free, Muses Woman Born a Slave,”1 Marie recounts several of the significant events of her life, from being born enslaved to escaping and seeking asylum in the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony and her later life in Brooklyn. In Brooklyn, she had married, had a child, and worked for many years, first as an educator and then as a laundress and housekeeper. However, Marie Ferribee’s story does not begin in New York; nor does it begin in the Freedmen’s Colony. Marie Ferribee’s story begins with her mother, Annice Jackson.

Annice Jackson was a force of a woman. She was a soulful singer and a skilled cook. Annice was also infamous in eastern North Carolina for her “folklore songs” that enslavers believed inspired rebellion among enslaved populations. Only five months after giving birth to her second daughter, Annice and her children were sold in Elizabeth City. This was not Annice’s first experience being sold. She was familiar with the inhumane buying and selling of human beings that was intrinsic to the slave-labor system. As an enslaved person, Annice was considered a commodity, and her unmistakable beauty and impressive kitchen skills made her highly sought after. However, she was determined to make her children’s first time on the auction block their last.

Some years later, amidst the uproar of the Civil War, Annice attempted to liberate herself and her daughters, Alice and Marie. Her effort was met with severe retaliation, and she was beaten in front of the girls. Despite her wounds, she managed to escape and led them to shelter. When they were safe, she collapsed. The day passed, and the sun set as Marie and Alice cried over their mother’s brutalized body, believing she was dead. But in the light of the moon, Annice rose, and the trio continued on through the North Carolina wilderness.

Word had gotten out about Annice Jackson and the voice she used to incite rebellion among enslaved folks. She, Alice, and Marie were captured and put aboard a boat set to return them to Elizabeth City. But Annice, determined to see her plan of self-emancipation through, ripped a piece of white fabric from her skirt and used it to flag down a Union gunboat. The gunboat rescued them and took them to Roanoke Island.

Annice and her daughters were three of the thousands of newly freed people who sought asylum in the Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony. The island was a popular destination for Black Americans seeking refuge, with approximately 3,500 freedpeople inhabiting the colony at its peak. On the island, Marie and Alice lived with their grandparents, who had migrated there two years before. Annice, however, could not remain with the family because of her status as a wanted woman. With her children safe, she left Roanoke Island in search of somewhere she could exist without the threat of recapture. Annice would reunite with at least one of her daughters years later, but for the time they were forced to live apart.

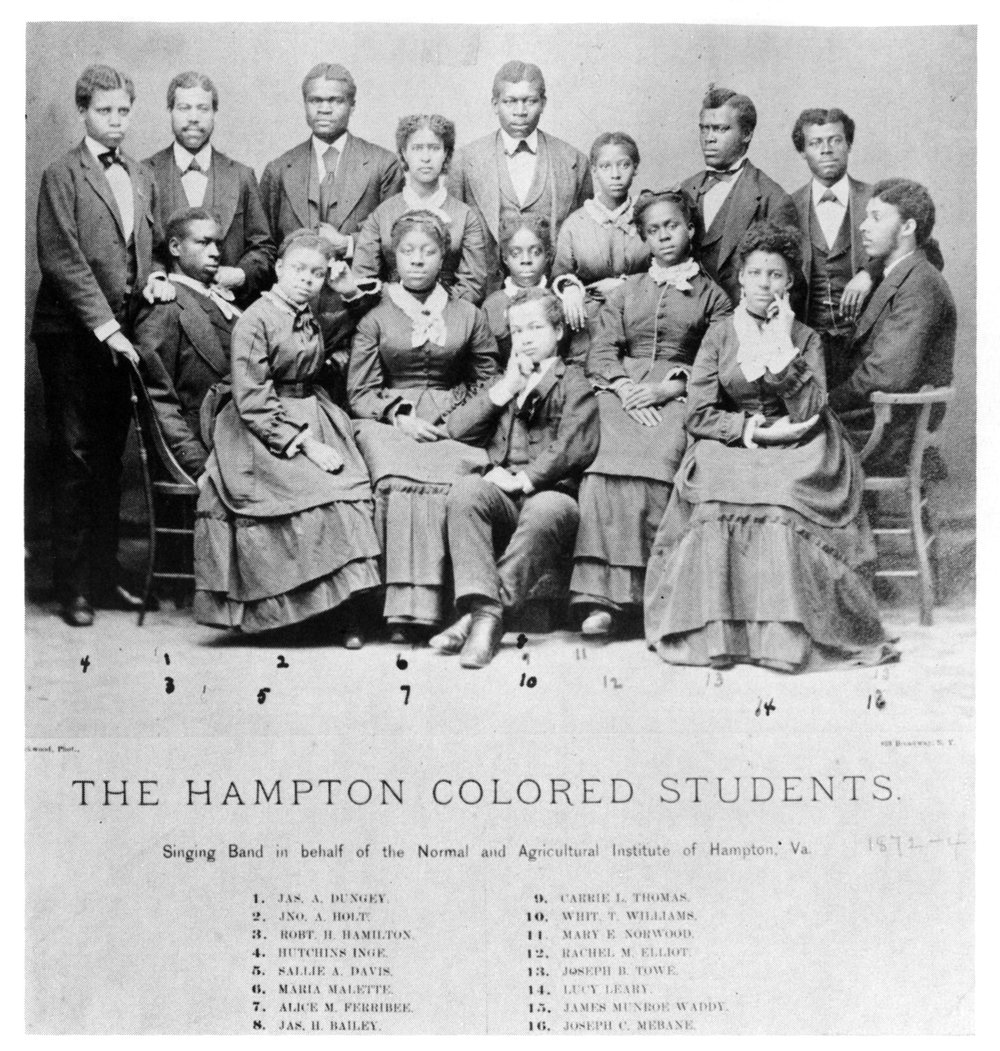

Several years after their arrival on Roanoke Island, the sisters left to pursue higher education. Blessed with the musical talents of their mother, Alice received a scholarship to attend the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute as a Hampton Jubilee Singer. Alice is pictured in the seventh position in the photo below. Marie attended alongside her sister, paying her way through school and graduating at 18.

Known today as Hampton University, Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute originated as an institution dedicated to educating the children of formerly enslaved people. The latter half of the 19th century saw widespread erections of schools with similar missions. Today, these institutions are classified as Historically Black Colleges and Universities, or HBCUs. Some HBCUs, like Hampton, were established by affluent white abolitionists and military personnel looking to train selected Black youth, teaching “respect for labor” and replacing “stupid drudgery with skilled hands”.2 Other institutions, like State Normal College for Colored Students (now Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University), were established by African Americans to provide newly freed Black folks with opportunities to acquire technical and mechanical skills, opening the door to the possibility of social mobility.

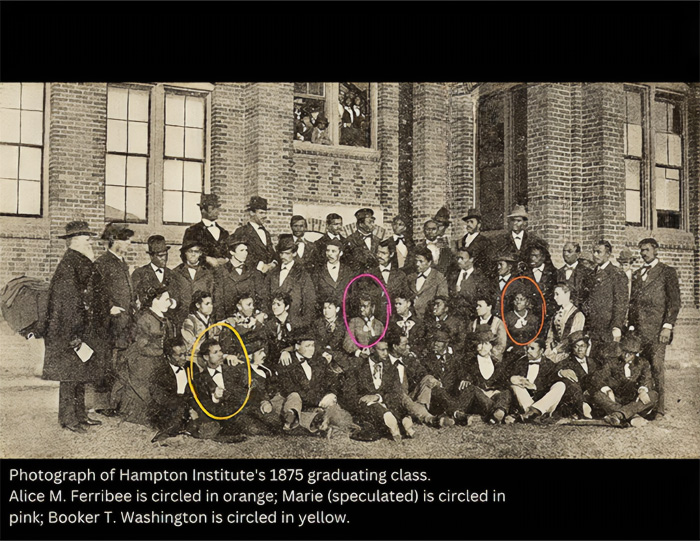

At Hampton, the sisters learned alongside other Black students, receiving industrial, moral, and educational training. One of their classmates was a young man from Virginia named Booker T. Washington. Washington later became a prominent orator, author, and educator and helped to found the Tuskegee Institute, a historically Black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama.

Upon graduating from Hampton, both Alice and Marie became teachers. Alice taught in Perquimans County, North Carolina and Rocky Ford, Virginia. She married Peyton Lewis, another member of the Hampton Institute class of 1875, and they had five children together. Lewis became a reverend in the Methodist Episcopal church and Alice joined in his ministry playing organ for Sunday services. She also dedicated herself to teaching religion through the lens of homemaking. Her lessons emphasized the virtue of neatness and cleanliness and the importance of providing children with good examples of how one should live.

Marie praised Hampton for the doors it had opened for her and returned to Elizabeth City, looking to use her training to lead others through the same thresholds. However, when she applied for a teaching permit and requested a building to teach in, her appeals were denied. When that door closed, Marie, determined to “teach [her] people in payment for the advantages [she] had received,”1 found a proverbial window and propped it open. She held school in an old lizard-infested shack. Marie taught in Rocky Ford, Virginia and Guinea Mills, a town in Currituck County, North Carolina.

When Marie was only a few years into her teaching career, her mother fell ill. Annice Jackson had found her way to Brooklyn, New York since leaving her daughters with her parents on Roanoke Island. Marie migrated north to care for her mother. In New York, she married, becoming Mrs. Watkins, and had one son named Henry. Marie attempted to continue her work as an educator but found limited opportunities for Black female teachers in the North, so she took up work as a housekeeper and laundress instead.

For Marie, Brooklyn was a turning point. As a free Black woman in a more progressive northern environment, Marie could participate in the seemingly mundane activities her white counterparts had enjoyed for years. She could see a picture show at the theater. She could ride in cars, taking in the sights and sounds of the bustling city. More than that, Marie could walk proudly in Brooklyn, free from the haunting scenery of plantations, the makeshift schoolhouse overrun with lizards, and the auction block where she was sold before her first birthday. Brooklyn signified the beginning of a liberated life.

Marie cherished that liberty as long as she lived. She remained in New York for the rest of her days, continuing her work in the service industry until she was 82. By 1949, Marie lived by herself in a small Brooklyn apartment, surrounded by well-nourished plants and pictures of her loved ones. Though her mother had died some years before, her presence filled the room, a photo of her making beaten biscuits, a beloved southern classic, on display. Also on display was a keepsake from Marie and Alice’s days at Hampton: a photo of the Hampton Institute Class of 1875 featuring Marie (second row, sixth from the right) and her sister, Alice (second row, second from the right), as well as Booker T. Washington (first row, second from the left).

Marie had no desire and no reason to return to the South. Her mother and grandparents had long since been buried, so she set down roots in Brooklyn. Daughter to Annice, sister to Alice, mother to Henry, grandmother and great-grandmother to dozens, and teacher to many, Marie Ferribee’s long life was replete with sacrifice, service to her people, and love. She exemplifies the idea that revolution is not always loud; that sometimes revolution is found in simply continuing to exist and press on.

Bibliography

1. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and Violet Brown. “Nov 11, 1949, Page 3 - the Brooklyn Daily Eagle at Brooklyn Public Library.” Newspapers.com, November 11, 1949. https://bklyn.newspapers.com/image/686229370/?terms=Marie%20Watkins&match=1.

2. Hampton University. “History – Hampton University About,” n.d. https://home.hamptonu.edu/about/history/.

3. Hampton institute, Hampton, and The Library of Congress. Twenty-Two Years’ Work of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute at Hampton, Virginia. Internet Archive. Hampton : Normal school press, 1893. https://archive.org/details/twentytwoyearswo00hamp/page/44/mode/2up?q=ferribee.