Last updated: October 4, 2024

Person

John Samuel Hawkinson, Jr.

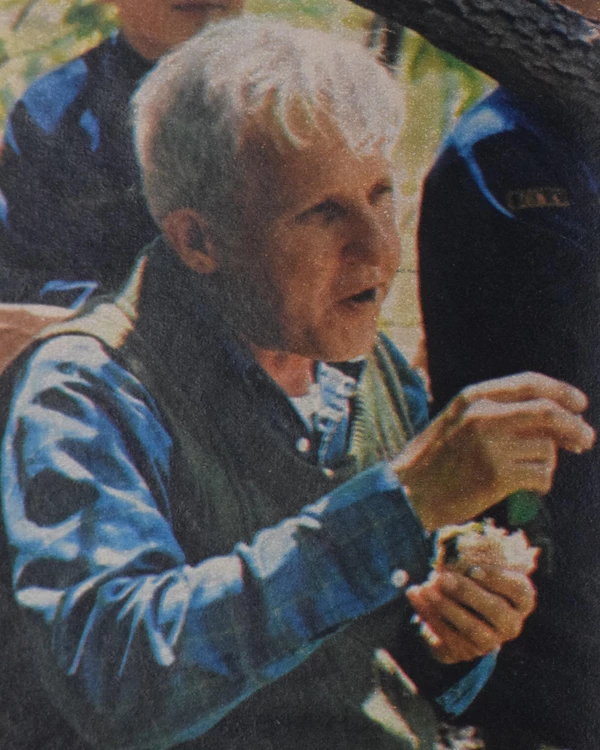

Photograph by Perry C. Riddle, courtesy of Joseph Gruzalski

John Samuel Hawkinson, Jr was a skilled artist and influential conservationist who used his talents to connect children to the natural world. He and his wife, Lucy Ozone Hawkinson, were a tag-team duo who illustrated and wrote children's books together. John's passion introduced thousands of young people to Indiana Dunes. He traveled around to different schools and libraires to teach about art and nature and was also a boy scout leader for decades. He and Lucy were members of the Save the Dunes Council and held on to the last privately-owned piece of dunes property in the area that would become the Port of Indiana.

John Hawkinson was born in Chicago on November 8, 1912, to Frances (Jackson) and John S. Hawkinson Jr., the third generation to bear his name. His paternal grandfather, born in Sweden in 1832, allegedly escaped the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 by crossing the Chicago River. John's father, a building contractor and avid naturalist, gave him two great gifts: a pair of binoculars and a deep appreciation for "the land and what it provides."

In the early 1920s, John was introduced to the Indiana Dunes as part of a Boy Scout group from Hyde Park on Chicago's South Side. Despite later becoming a champion of education, John recalled feeling alienated in school, largely due to being left-handed.

John's wife, Lucy K. Ozone, was born on May 11, 1924, in San Diego County, California, to Japanese immigrants Sei (Shiokawa) and Koichi Ozone. In her senior year at South Pasadena High School, the attack on Pearl Harbor plunged the U.S. into World War II. Shortly after graduating in 1942, Lucy, along with her family, was incarcerated at the Manzanar War Relocation Center—one of ten American internment camps established after President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. Manzanar housed 10,000 of the more than 110,000 Japanese Americans forcibly detained in remote military-style camps.

Image caption: Undated photograph of Lucy Ozone (Courtesy of South Pasadena High School Alumni Association)

Over time, the War Relocation Authority shifted its focus to helping internees resettle, encouraging relocation to places like Chicago, where the first regional office was opened. Although it is unclear when Lucy left Manzanar, President Truman dissolved the WRA in 1946, allowing Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast. Many found their homes and belongings either stolen or sold.

John’s life before WWII remains largely undocumented. He served in the U.S. Army from January 1945 until the war’s end, as part of the 87th Infantry Regiment in the Italian Campaign with the 10th Mountain Division. He returned to Chicago decorated with a Bronze Star Medal.

By 1950, John was a struggling commercial artist attending night school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago on the G.I. Bill. It was likely during this time that he met Lucy, who was also studying there. That same year, John purchased two acres in the Central Dunes—5,000 acres of unspoiled Indiana dunes, sometimes called Dune Park after the nearby train station.

John's property was located off “Barking Dog Road” and cost him $400—$300 of which he borrowed from the seller. In 1950, this area was considered "everyone’s land"—vacant, unprotected, undeveloped, and wild. Soon after purchasing the land, John began taking scouts and schoolchildren to explore the dunes. That first winter, he built a small cabin for overnight stays, dragging lumber on a homemade sled across the snow to his property. He embraced an "open door" policy, welcoming friends, acquaintances, and even strangers who had heard of his retreat. The key to the cabin was hidden in a nearby tree for easy access.

The land surrounding John's cabin was part of the vast, undeveloped Central Dunes, where many parcels had been acquired by real estate holding companies. He and his few neighbors used what they believed was an ancient Indigenous trail to reach their homes from Barking Dog Road. To transport gear, they would load rafts and pull them along the Lake Michigan shore through shallow water from the nearest lake access point.

Locals referred to John as their “local Thoreau,” complete with his own small pond. Though he attended the Art Institute of Chicago, he claimed he learned to paint in the dunes. John would set up his easel outdoors in all kinds of weather. He described his watercolors as a blend of "oriental and occidental styles," reflecting the duality of the dunes and the world at that time. He was connected to a local artistic circle and knew painters like Emil Armin, James Gilbert, and poet Charles G. Bell, who frequented shacks near his own.

Real estate holding companies were waiting for industry to come to the dunes. Southern Lake Michigan’s geographic location and access to land and water transportation had already helped Gary succeed in 1906. Despite the industrialization, John “wasn’t too bothered from Gary, for at his dunes, he was free. Sure, there were some filthy smudges he had to pass through, but the contrast heightened the sense of freedom.”

In 1952, Bethlehem Steel, the second-largest steel producer in the U.S., announced plans to purchase the Central Dunes, including John’s land. That same year, the Save the Dunes Council was formed in response, declaring, "There are other places for steel mills and harbors” and “there is only one Indiana Dunes." John quickly became a member of the group, committed to preserving the land he had come to love.

As early as 1952, a land holding company offered John $1,000 for his property, but he wasn’t interested in selling. As he explained, "I never had any money—and never felt the need for it. But I had fallen in love with the land—and that I did need."

With the completion of the St. Lawrence Seaway project, speculators saw potential for a new Port of Indiana to bring in ships from all over the world. Hawkinson’s offer quickly doubled to $2,000, and then jumped to $5,000; companies were aware that opposition was building, and they were willing to pay premium prices to control the land quickly.

John and Lucy married on September 14th, 1953 in Cook County, Illinois. They continued to live on the South Side of Chicago but would frequently visit their cabin in the Dunes. In the mid-1950s, John’s artwork began to be exhibited around the region. His work, greatly influenced by Lucy, was noted for its "oriental flair." He specialized in watercolor paintings on Japanese rice paper, which he preferred for its soft texture and subtle effects. His paintings were marked by "a definite Japanese influence in their simplicity, focus, and style."

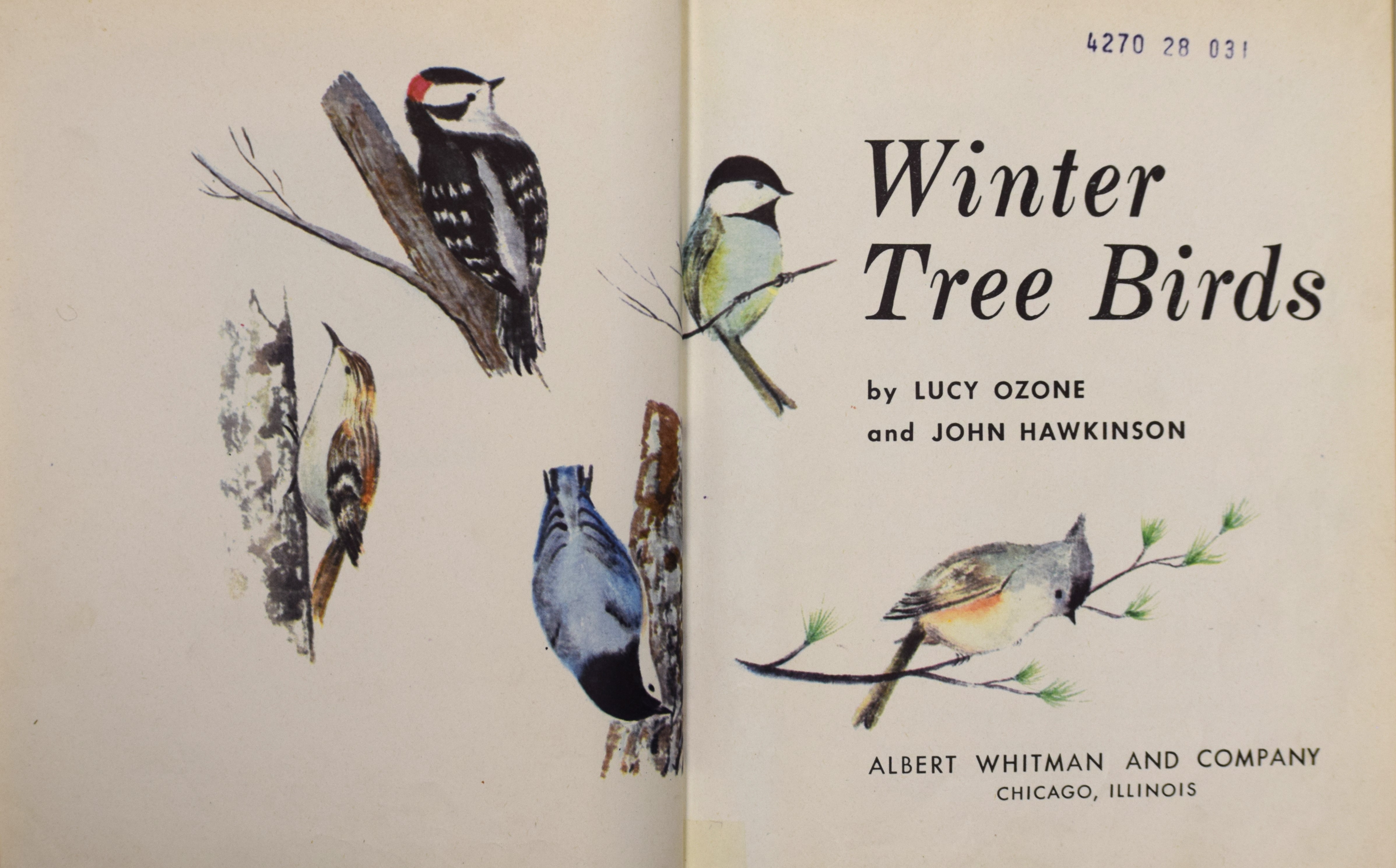

In 1955, John exhibited his duneland and bird paintings at the home of Mr. and Mrs. T. W. Pape in Furnessville, which today is known as the Schoolhouse Shop. That same year, he showed Snow in the Hills at the Chesterton Art Show, a precursor to the now-famous Chesterton Art Fair. John focused on exhibiting locally so residents could appreciate the beauty of the dunes—a place he felt must be preserved. Around this time, he also began collaborating with his wife, Lucy, on children's books. Lucy, already an experienced illustrator of school textbooks and picture books, helped publish their first joint effort, Winter Tree Birds, in 1956. Two years later, their first daughter was born, followed by a second daughter a few years later.

Image caption: Title page of John and Lucy's first book together; Winter Tree Birds, 1956. (Courtesy of Joseph Gruzalski)

Meanwhile, Dorothy Buell, president of the Save the Dunes Council, sought political support to protect the dunes. In 1958, she took the advice to contact Senator Paul Douglas, who introduced his first bill to establish an Indiana Dunes unit within the National Park Service. This marked the beginning of one of the most prolonged legislative battles in U.S. history to protect a particular landscape.

Dorothy Buell praised Douglas for his commitment, saying he had the “vision” and plunged into the fight. Thomas Dustin, director of the Indiana Izaak Walton League, offered a more measured view: “Until this time it had been an impossible campaign.”

“But any expectation the council and its allies might have had of a quick victory now that Douglas was their champion soon died. While the park bills sat in committees, the industrial and political interests intent upon the development of the [Central Dunes] site exploited the customary advantage of private industry over conservationists in Congress—they simply proceeded to develop the land” (Sacred Sands).

By 1962, most of the dune land had been sold off, and hope among conservationists began to wane. The Hawkinsons were offered $25,000 for their land, but they turned it down. Although Save the Dunes continued to rally support, one undeniable fact hampered their efforts: industrial companies already owned nearly all the land. Despite the efforts of Senator Douglas and Save the Dunes, Bethlehem Steel remained unmoved. While the company had not yet secured the right to build, they had the authority to destroy. They contracted to haul away 2.5 million cubic yards of sand from the Central Dunes to Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois—a bitter irony, as Northwestern students had long used the dunes for educational excursions.

The news came as a great shock to Douglas, Hawkinson, and the rest of the Council. The next day Thomas Dustin called it “an infamous Pearl Harbor for conservationists everywhere.” Douglas and his allies insisted that Northwestern could not escape moral responsibility for the deed, but protests proved futile. Dorothy Buell remembered how in early winter 1962, as the bulldozers went to work, “Senator Douglas stood beside me, watching, with tears running down his cheeks” (Sacred Sands).

In a final, desperate effort to save the Central Dunes, Senator Douglas introduced S. 650 at the start of the 1963 congressional session. “The bulldozers are poised, Mr. President, but the dunes still remain and can be rescued,” he declared. But it was no use. Within a year, the heart of the Central Dunes was gone. “The wildest and largest area of the Dunes outside the Indiana Dunes State Park, the center of maximum ecological diversity, the landscape of moving dunes where Cowles did his first research on plant succession—was no more” (Sacred Sands).

A few years later, the battle over the lakefront culminated in what became known as the Kennedy Compromise, which established both a port and a park. While it was seen as a win for most, Senator Paul Douglas, John Hawkinson, and the rest of Save the Dunes were deeply disappointed. They faced a difficult choice: accept the compromise, which would create a federally protected lakeshore—albeit on land inferior to the dunes they had fought to preserve—or continue the battle indefinitely, risking the loss of everything. In 1966, the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore became a reality, though it did not include the central dunes that had initially inspired the movement.

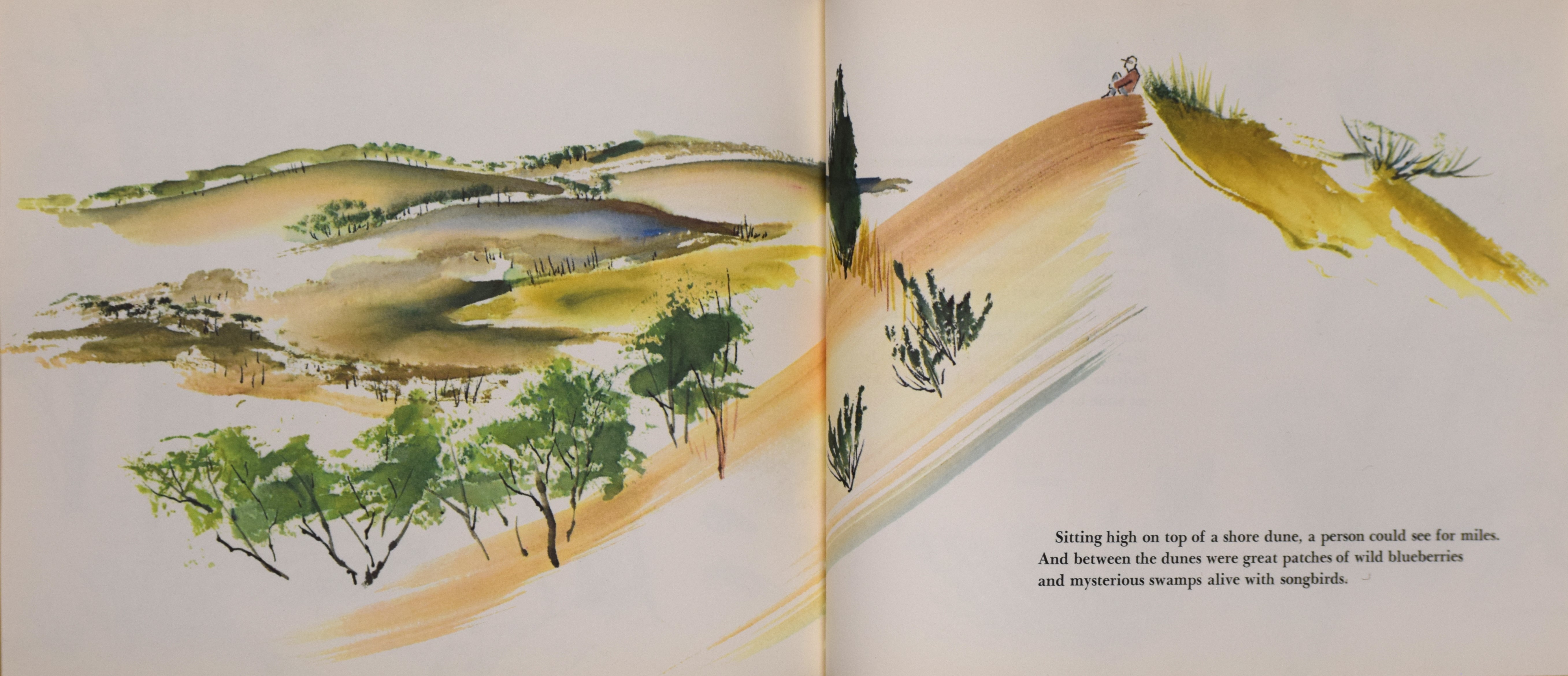

Image caption: "Sitting high on top of a shore dune, a person could see for miles. And between the dunes were great patches of wild blueberries and mysterious swamps alive with songbirds." Illustration by John Hawkinson from "Moving Hills of Sand," 1969. (Courtesy of Joseph Gruzalski)

That same year, Hawkinson, described as a defender of “forlorn causes,” was interviewed by Ridgely Hunt III of the Chicago Tribune. Hunt wrote, “In the struggle for Hawkinson's two acres, Bethlehem will eventually win, of course, and Hawkinson will lose. The rest of the forest will come down, and the beech, the maple, the oak, the gum trees will die. The indigo bunting will find another home. But Hawkinson will savor a more important victory: By clinging to his land until the end, he helps to persuade Bethlehem executives that they must not oppose the national lakeshore. When the lakeshore plan is realized, he can retreat from the field of battle, his honor still intact. But he will have one personal loss to mourn. ‘I still love the place,’ he says. ‘That's what hurts.’”

By the time the bill passed, John and Lucy were one of only two remaining private landowners in the Central Dunes. They were offered $45,000 for their property and, before long, were asked to name their price. They still didn’t have one. The other property was owned by Drs. Knute and Virginia Reuterskiold, fellow members of Save the Dunes, who also declined an offer—this time, for $100,000 for their 10 acres. Both families supported the creation of the national lakeshore and would have sold their land to the National Park Service, had it been included in the plan.

Bethlehem Steel tried to break their resolve by making access to their lands difficult. They received permission from the Porter County Commissioners to close Barking-Dog Road, cutting off access to both the Hawkinson and Reuterskiold properties. However, with the help of Save the Dunes attorney Edward Osann, Jr., the families took the company to court, and Bethlehem backed down. Neither financial pressure nor mild intimidation could move them. But because the Reuterskiolds' land was critical to the port's construction, the Indiana Port Commission eventually claimed it through eminent domain. Despite fighting the decision in various courts, the Indiana Supreme Court upheld the ruling in 1967. The Hawkinsons now held the last remaining private land in the Central Dunes.

Bethlehem proceeded with the construction of its plant, designing it around the Hawkinsons' two acres. A gate with an armed guard was installed, and only John and those accompanying him were allowed access; friends were turned away, effectively ending the open-door policy John had cherished. This restriction weighed heavily on him. He still took Boy Scouts to the dunes, but one by one, they watched the features they had come to love—once a hallmark of the wilderness—disappear.

But he still had the 2 acres, and a buffer of several more that the company left. Bethlehem knew that they would have to go to court again if the Hawkinson property was physically affected by construction. Though it was not the same wilderness, a few acres were enough for wandering in. Life remained in the little pond, skiing was still possible, and so was archery. Except for the construction noise, vibrations, and dirt and dust in the air; Hawk and his scouts could still imagine themselves in the middle of their old wilderness.

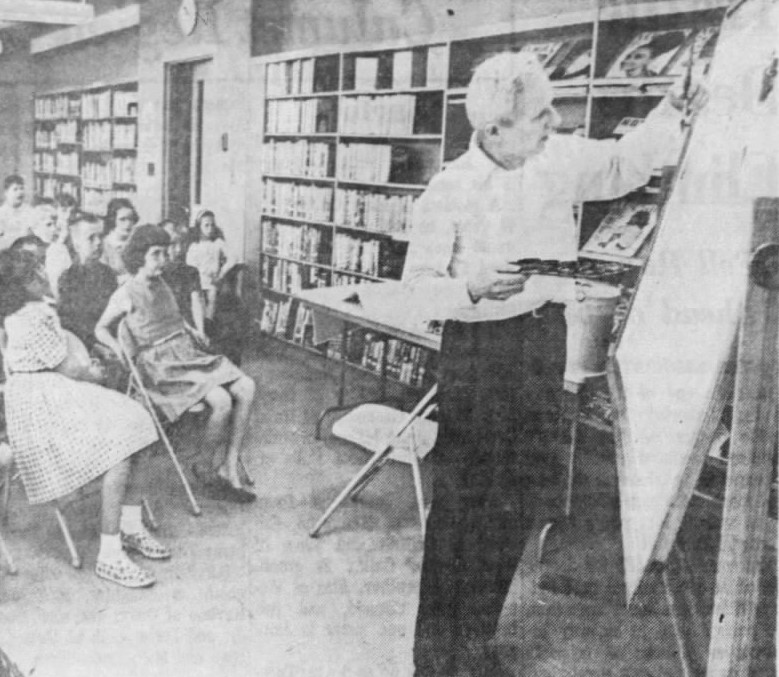

Image caption: John Hawkinson demonstrating painting techniques to a classroom of students. (Photograph from the Times; Hammond, Indiana, 1965)

Throughout the 1960s, John displayed his artwork in libraries and schools across the Midwest and frequently led painting programs. A 1968 article from Tipton, Indiana, offers insight into his character: “His freedom of motion with his left hand holding a wide, flat Japanese brush is grace itself.” He is described as “sloppily dressed in old corduroy trousers and a baggy cotton flannel plaid shirt—but no hippy,” with short hair and a clean-shaven face. During his programs, he created rhythm bands with children using "instruments" made from everyday items like milk cartons and cereal boxes. He even improvised dance steps while painting, showing students “a way of looking at and becoming acquainted with nature.” The article noted, “It gave Mrs. Havens and me a warm feeling to know there are still people like John Hawkinson left in this troubled world.”

In 1970, during a program in Minneapolis, John used makeshift instruments—ice-cream carton drums, box harps, and panpipes—and painted to the rhythm of the music, encouraging everyone to join in. He believed in full engagement: “If you don’t dance, you don’t get to play the music.” By this time, John had become known as an artist, illustrator, and author of numerous children’s books. He was described as a "straight-talker, buoyant leader of nature hikes and bike tours, Swede, Quaker, scoutmaster, ex-GI, inventor, communicator, and free spirit." John had been a Scoutmaster for 35 years, and he took a hands-on approach to teaching art. He paid attention not to what students painted but how they moved while painting, blending in theories from Zen in the Art of Archery to help them connect body and mind. “The idea is to show people how to do it, not feed your ego,” he explained.

“My big kick is getting kids out of the cages,” John said. His commitment to getting children outdoors was evident in his guiding principles: “Don’t pick wildflowers. Don’t touch a tadpole without a wet hand.” He emphasized that it is our responsibility to keep children engaged with nature. “Kids have to be going and doing. It is the bounden duty of our society – parents and teachers – to keep them going and doing. They’ve got to get their feet wet.” He also invented teaching tools, such as a movie machine and a dispenser brush for children.

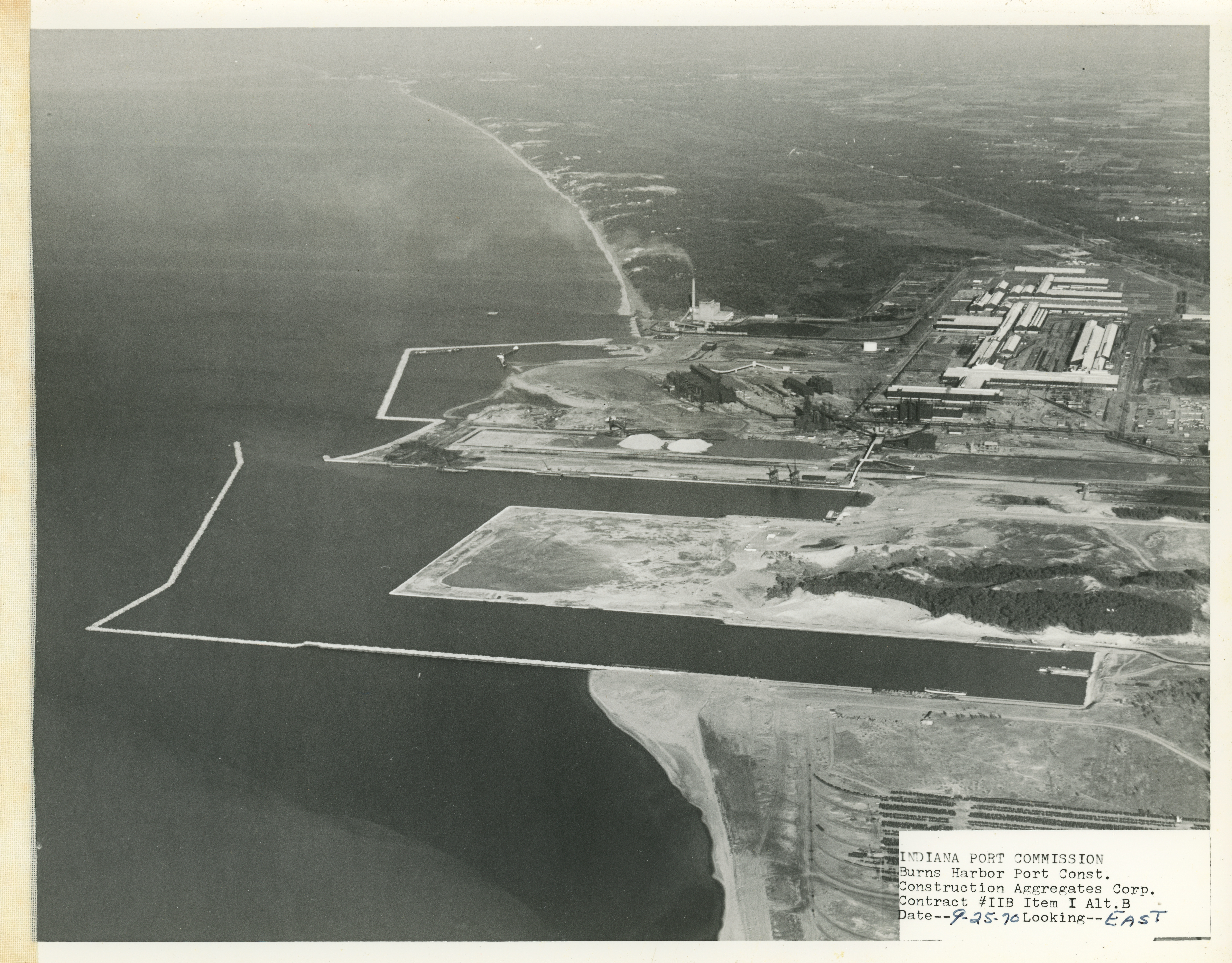

Image caption: September 1970 aerial photograph of the Port of Indiana under construction. The Hawkinsons' land is seen just south (to the right) of the Bethlehem Steel complex, at the extreme right-center of the photograph. (Photograph courtesy of the Steven Shook Collection)

By 1969, the Hawkinsons’ land had become an island of nature surrounded by industrial sprawl. Although agents periodically visited John and Lucy’s Hyde Park home with new offers, they refused to sell. That year, the Save the Dunes Council organized a Memorial Day picnic on their land to remember the Central Dunes. Lee Botts thought that the Council should invite the public to one last trip there that she called “Happening on Hawk’s Island.” A flyer stated it was to “look at what has happened all around, when nature lost the battle.” Cleared with Bethlehem in advance, groups of families were able to carry their picnic baskets through the gates and past the guards armed with pistols, white hard hats, and radios. Beyond the guards, Hawk’s Island—a small cluster of hills—rose like a mirage above the industrial landscape. Bird’s foot violet, columbine, and lupine greeted the visitors, just as they had each spring for generations.

From the crest they could look back over their shoulders at the Bethlehem Plant and Port of Indiana taking shape. Beyond that they could see smaller buildings of Midwest Steel. The mills had been painted a two-toned sand color to match the dunes that were no longer there. But as they looked forward, they were met with the familiar sight of a small pond near John’s lean-to cabin.

The skies were clear, and the weather was warm. Picnickers reminisced all day, trying to recall the old landmarks that were wiped out. Mud Lake was gone, as were Howling Hill, Crater Hill, and other familiar places. But for the afternoon—the Central Dunes lived on. Although the little pond had dried up, the cabin’s pilgrims were once again enveloped in a space that seemed remote from everything around it. Someone brought a guitar and the group gathered to sing songs. A great bonfire was lit, food was prepared, and a festive spirit prevailed. “If the adults had heavy hearts- they did not show it.”

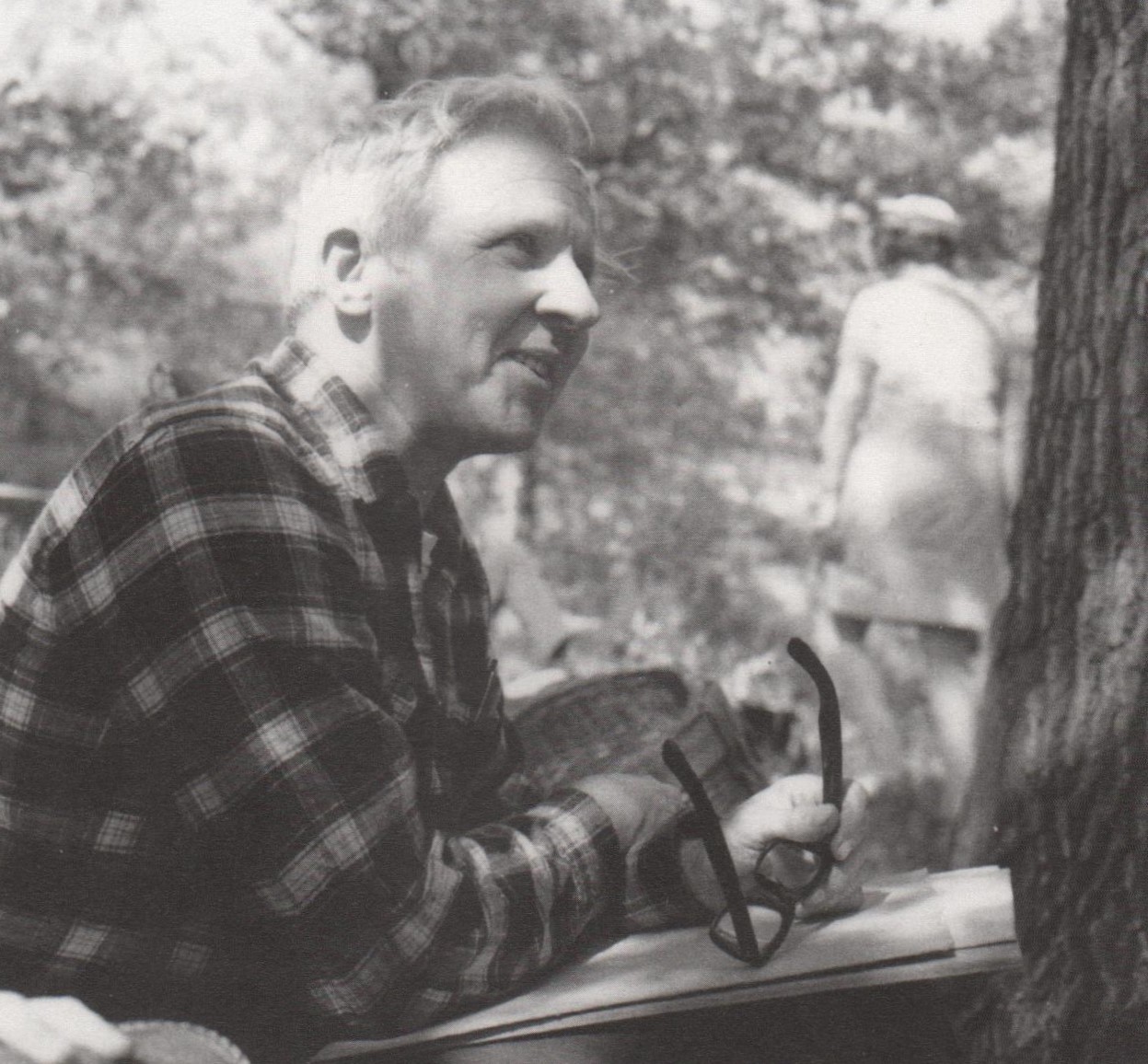

Image caption: John Hawkinson seated in his "island." (Photograph by Nancy Hays, 1969)

Children wrote haiku poetry and presented them to John, who sat on the ground leaning his back against a tree. One girl wrote:

“There is no safety in the woods;

Footsteps of men are among the trees.”

In 1969, the national environmental movement was beginning to build momentum. The little band gathered at Hawk’s Island could not help but wonder what would have happened if the “Age of Ecology” had come a decade earlier—just as their predecessors must have wondered what might have been had World War I not intervened. That same year, John illustrated Moving Hills of Sand, a story by Julian May about Indiana Dunes and the efforts to protect them.

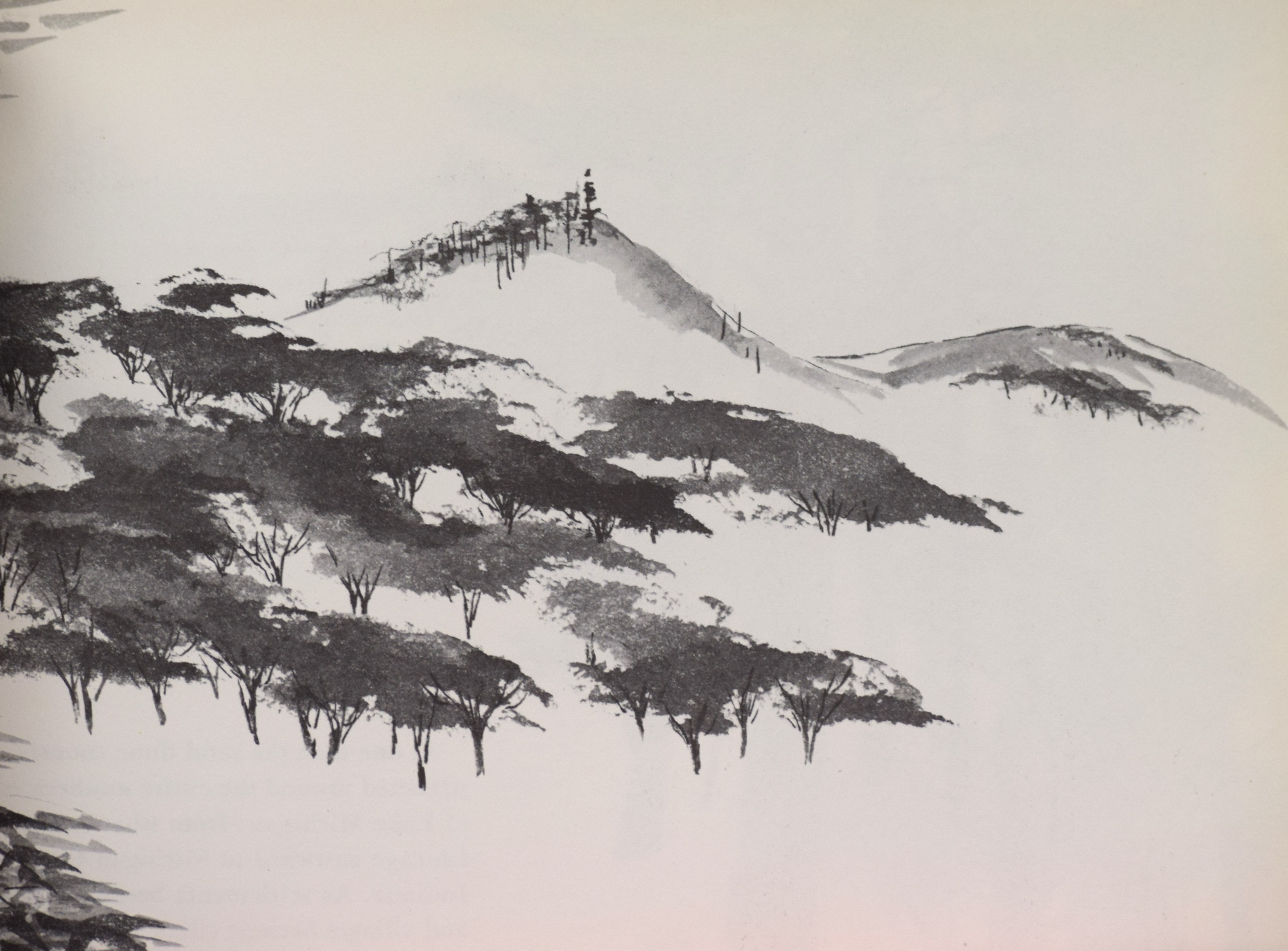

Image caption: Illustration by John Hawkinson from "Moving Hills of Sand," 1969. (Courtesy of Joseph Gruzalski)

Hawk’s Island came to an end in 1970. Lucy was diagnosed with cancer, and the family’s only asset to cover the medical bills was their land in the dunes. “It may have been a coincidence, but the day my wife went into the hospital, they offered me $25,000 and gave me 48 hours to decide,” John recalled. This time, he couldn’t refuse. They sold their two-acre island and purchased an old farmhouse in Lawrence, Michigan. Lucy, just 47, passed away the following year at Borgess Hospital in Kalamazoo.

After Lucy's death, John raised their daughters and continued working with children in rural southwest Michigan. His lifelong mission remained “to touch kids to the land and bring them together.” He frequently returned to the Indiana Dunes for events and often visited the Save the Dunes Council Shop in Beverly Shores. There, for a donation to the cause, he would paint dune scenes in minutes based on the customer’s wishes. He believed each picture should come from a personal connection between the buyer and the artist. He also continued illustrating haiku-inspired poetry written by visitors.

In 1973, he took a group of boy scouts to Cowles Bog in Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. From there, they could see the industrial complex that had replaced the once-pristine Central Dunes. A reporter captured an exchange between John and one of the boys: "Do you own this land?" the boy asked. "Any time my foot touches the ground, it’s mine for that instant," John replied, plunging ahead with the scouts in tow.

Image caption: John Hawkinson and a group of scouts investigate plant life growing on a sand dune. (Photograph by Perry C. Riddle, 1972; courtesy of Joseph Gruzalski)

As they trekked through the dunes, they passed lupine, phlox, and puccoon flowers thriving in the sandy soil. John pointed out, “This trail was once the stagecoach route around the lake to Chicago, running between the hills and the bog.” They worked together to dislodge a giant log from the beach, having too much fun to even realize they were learning physics and teamwork. John stopped for lunch to tell stories. “All this was pine forest,” he said with a wave of his parsley sandwich. “They took all of it to build Chicago.” Reflecting on the impact of industry, he remarked, “You can’t confuse progress with civilization. If we’re not civilized, it doesn’t make any difference whether you’ve got progress. It’s either Genghis Khan or a steel company. Who wants to be the winner?”

Later, the group used a seine net to explore a pond for small lifeforms, following John's golden rule: “You don’t take any creature, rock, or plant from nature when you’re with John Hawkinson.” Afterward, they returned everything to the water. “We must leave them for the next fellow,” he reminded the boys.

As the day wound down, the boys pulled on dry clothes, gathered their gear, and began the hike back. The bluffs, the lake, the black-oak forest, the pond, and the swamp had slowed the eager adventurers. They found it even more difficult to keep up with their leader, “who seemed to be tireless.” The reporter joked that while riding with the kids back to Chicago, “John will probably have something to say about what the automobile has done to nature.”

In 1979, John moved to Winter Haven, Florida, where he continued his passion for art and education, volunteering at a local elementary school. “He just walked in one day 15 years ago and announced he had ideas for the kids. We’ve been using his ideas ever since,” recalled a school official. He married Peggy Muirhead MacQueen, a fellow bird-lover and educator. She was a biology instructor at a local college whose lifelong interest in birds led her to study them all over the world. John illustrated her lectures with his artwork.

Image caption: John Samuel Hawkinson Jr. (Photograph from findagrave; uploaded by Eva Hopkins)

John passed away at Winter Haven Hospital on June 14, 1994. His daughter Anne reflected on her father’s legacy, saying, “He felt he had something to teach. He had a real vision about art. He believed every child could become an artist—all they needed were the tools and someone to show them how.”

The content for this article was gathered and written by Joseph Gruzalski, a researcher with Indiana Dunes National Park.

Sources

- Ela, Jonathan; The Faces of the Great Lakes; Sierra Club Books, 1977.

- Engel, J. Ronald; Sacred Sands; Wesleyan Unversity Press, 1983.

- Riddle, Perry C.; Nature's Wonders Are for Everybody; Boys' Life Magazine, January 1973.