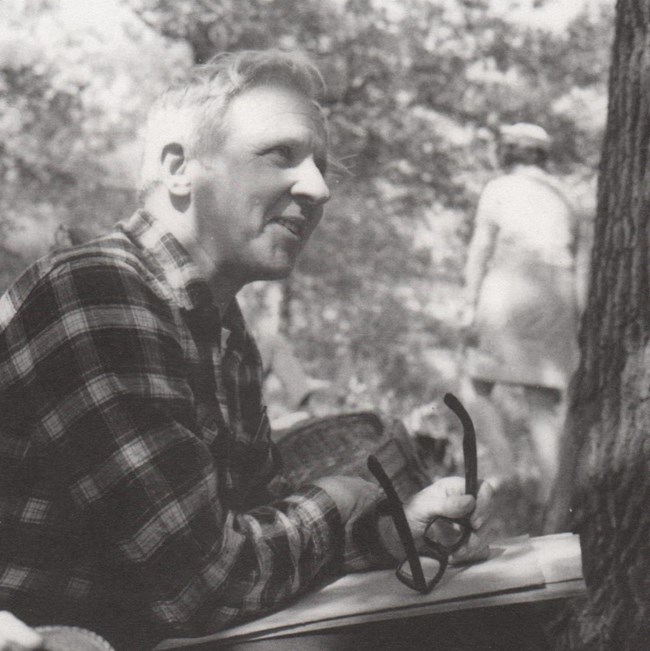

At first glance, the two antagonists look pathetically ill-matched. On one side stands Bethlehem Steel, a corporate giant, the nation's second-largest steelmaker, defended by platoons of vice presidents and lawyers and armed with a thousand bulldozers. Pitted against this mighty force is a mild, gray-haired artist named John S. Hawkinson who illustrates children's books, leads a Boy Scout troop, and defends forlorn causes.

These two improbable combatants are fighting specifically for two acres of wooded sand dunes that Hawkinson owns near the shores of Lake Michigan in Indiana. The land is immensely valuable. Hawkinson prizes it because, among other things, it is the only place within 50 miles of Chicago where you can still hear a bobwhite. Bethlehem covets it because it lies right in the middle of the company's new 400-million-dollar Burns Ditch steel complex. Thru obstinacy and litigation, Hawkinson has compelled Bethlehem to maintain a right of way so that he can reach his plot, which is entirely surrounded by the steel company's vast property. The Hawkinsons like to go there to pick wild flowers, which they press in books, and their two little girls enjoy tobogganing on the snowy dunes in winter.

Overshadowing both Bethlehem and Hawkinson, however, is the federal government as embodied by the national park service, which seeks to acquire about 11,000 acres at the end of Lake Michigan for something called a "national lakeshore," a sort of nature study and recreation area. In this endeavor the park service has been opposed by several steel companies that want to use the dunes for heavy industry and by several Indiana politicians who hunger for the employment and tax revenue that the new mills would provide. Anyway, many Hoosiers don't want 100,000 Chicagoans trooping out there every weekend with their umbrella tents, bathing suits, and beer coolers. In this attitude the proponents of the national lakeshore believe they detect overtones of racism.

Bethlehem doesn't have much to worry about any more. It has already drained the cattail swamps, chopped down the black oak forest, flattened the dunes. The beavers have been exterminated or driven away. On 3.300 acres where once the blackbirds sang. Bethlehem erected a 160-inch sheared plate mill, a cold-rolled sheet mill, and a tin mill. An 80-inch, hot-rolled sheet mill will be completed this year. "The end," says Edmund F. Martin,Bethlehem's chairman and chief executive officer, with understandable pride, "is not in sight." Before they're thru, they intend to have a "fully integrated plant" there. With all these buildings already standing [chocolate brown, sand beige, and light green to harmonize with the surroundings], the government isn't likely to evict them.

But Inland Steel never got around to building anything on its 840 acres in the dunes, and now it fears the park service will cut it out of the game. Inland consequently has fought the lakeshore plan vigorously. It even hired former Postmaster J. Edward Day to plead its cause, and Day came up with some real posers. How, he demanded of a House interior subcommittee last spring, will they handle those 20,000 automobiles a day when Chicagoans start pouring out to the shore on hot week-ends? You'd have to herd them across the railroad crossing at a rate of better than 60 cars a minute, Day calculated. Besides that, the place would be dangerous. "The water," Day told the congressmen, “often is treacherous, the waves high and fast. They will need 20 lifeguards on the beach."

Then there's the money-23 million dollars by the most recent reckoning. "It would seem only common sense to slack off on these big domestic spending programs," says Indiana's Rep. Charles A. Halleck.

The dunes lake shore has its defenders as well as its foes, chiefly Sen. Paul H. Douglas of Illinois, but also including a covey of congressmen [Indiana's Senators Vance Hartke and Birch E. Bayh, Rep. J. Edward Roush] and private citizens. One private group, the Save the Dunes council, has paid for Hawkinson's legal battles and will take a piece of the action If he ever sells. Carl Sandburg, the nation's unofficial laureate, is cited in behalf of the cause [“The dunes are to the midwest what Grand canyon is to Arizona ..."], and even President Johnson is invoked [“... our land will be attractive tomorrow only if we organize for action and rebuild and reclaim the beauty we inherited"].

At the moment, beauty is taking a licking in the dunes. The pond that once lay below Hawkinson's cabin has been drained. Where once the pond shield and water lily grew, where the pickerel grass and leatherleaf flourished around the shore, where the wood duck and mallard nested and where the pied-billed grebe built his floating nest--this pond is dead. And if you climb the sandy slope behind the cabin, you see across a great, barren area, once a cattail bog, to a vast, brown, metal building from which rises the hum of machinery. Intermittently from the building comes a startling crash as if there has been a frightful accident.

Hawkinson bought his two acres 18 years ago, paying $400. He built the cabin himself and carried in the lumber on his back because no road led to his property. "It's not a cabin," he protests. "It's a shack," but he designed it so that the low lines and shed roof would blend with the dune's slope. He installed windows across the front so he could see his pond and an iron pump to give him water. The pump ran dry when the steel companies drained the land, and vandals have smashed out all the windows.

For several years no one bothered him here, and he loved his land with a wry and quiet passion. "You could sit in front of my cabin and spot where the birds were going to build their nests," he recalls. "You knew where they were going to be. They were like neighbors. There was an old Indian trail that ran right by my cabin, and I found arrowheads there. This was the greatest blueberry country in the United States. You could pick a bucket of blueberries in half a day, no problem."

Hawkinson looked upon his realm with the informed eye of the connoisseur. What the city dweller would see as a bird on a telephone pole, a pretty flower, a thicket of saplings, would become in Hawkinson's eyes an indigo bunting, a clump of lupin, a stand of aspen. He knew where to find wild asparagus and with his wife and children would gather a bunch as a delicacy for supper. He could pull up a sassafras root to brew a cup of tea and spot the hollow tree where the flying squirrels lived.

Most of the land was owned by the Consumers company, a Chicago ice and coal concern, but there were a few small owners like Hawkinson: Tony the goat man, a Swedish widow who ran a small chicken farm, a professor, a woman with an invalid husband. Hawkinson used to get water from the widow's farm because it was sweeter than the water from his own pump. In return he repaired her roof and ran in electric lines for her. The widow has moved into town now, and her farm is gone—demolished. The old farmhouse has been reduced to a few great beams, charred by the flames that consumed the wreckage. Of all the neighbors, only Hawkinson remains. The rest succumbed to blandishments and pressures.

"It started in the 1950s," Hawkinson says. “The Consumers company came and talked to me. They said the steel companies wanted to buy the land, but they said, 'We're not going to sell this land; it's too valuable for that.' Nobody quite believed these rumors. Everyone said, 'We'll never, never sell.’ But then they started to get the smell of the folding green."

The steelmakers had some folding green Hawkinson, too. "They started at $2,000," he says. “Then they went up to five grand, then 10, then 20, then 45. The last I heard, I could name my own price." [A spokesman for Bethlehem says merely that so far the company has been unable to reach an agreement with Mr. Hawkinson.]

Hawkinson is not a wealthy man. He lives in a spacious old walk-up apartment in Chicago's Hyde Park area where, in one end of his living room, he executes his drawings and paintings for children's books. Most of his work is charming. with a faintly oriental cast in the trees and flowers and a tender regard for the peculiar vulnerability of children [Their necks are too small for their heads, for one thing." he says]. He could probably make a great deal more money if he did not devote so much time to the Boy Scouts and the afflictions of suffering humanity. Last year he got himself arrested while trying to prevent the city from cutting down trees in Jackson park. He beat the rap, but he wasted days in court, and despite his efforts, 800 great, old trees were felled.

Hawkinson is a man of contrasts. Tho he has the mind of a philosopher and the face of an ascetic, he lunges thru life with the zest of a sailor. Tho he holds strong views, he states them so softly and in such a breathless torrent of words that it's hard to hear half of what he says. And tho he hungers for peace, he finds himself embroiled in unending battle. Despite his quiet voice and gentle manner, he is a fighter. In World War II he survived for months on the spearhead of the American advance thru Italy. His neighbors in the dunes had not been hardened in this sort of furnace, and one by one they cracked, took their money, and fled. The woman with the invalid husband stuck it out the longest. But they came on her at night with floodlights that glared into her windows and bulldozers that rumbled toward her house until the ground shook beneath her. This lasted all night, every night. “They bombed her out,” says Hawkinson. “You’d have to live thru an artillery barrage to understand what it was like." She was the last to sell.

Hawkinson has not encountered such extreme tactics. Aside from the loss of his water supply, the destruction of his pond, and the expulsion of the blackbirds and the beavers, he has little to complain about. "They've got a very nice real estate guy who comes to see me occasionally," he says. "He always offers me more money. I like to see him come, but I tell him he's wasting his time." His dealings with the steel company guards are similarly affable. "They stop me out there and say, 'Is everything all right?' Sometimes they say, 'What are you doing here?' I tell them, 'I live here.'"

But he doesn't live there, not with the windows smashed out of his cabin and no water for drinking and washing. In fact, during the summer he seldom goes there any more. “I like it better in winter because the shapes and forms are lovelier then and the colors are subtler. Besides, the dunes were never a place for people- just for children because children don't mind being uncomfortable." Along with the other wonders of nature, there are mosquitoes out there and ants, poison ivy, cactus, and a superfluity of sand that sifts inside your shoes and sticks on sweaty faces.

Hawkinson reveres the land despite these discomforts. He does not want flush toilets and air mattresses in the wilderness; he abhors them. Tennis courts and swimming pools, he holds, profane nature.

"If this is all the land means to you just recreation—then we are already well down the road to the brave, new world. If you're satisfied with a shuffleboard court, then they can substitute something else. You can stay at home in your astrodome. How are you going to develop a love for the land unless it means more to you than recreation? We need it for something more important than that. We need it for the kids to get out and study it, learn what nature is and how it works. Without that, we've got nothing.”

"God gave us the earth. He didn't give it to us to chew it up. He intended that we use it for something more than just growing potatoes to feed our faces."

But somebody must grow potatoes, and somebody must make 80-inch, hot-rolled sheet steel. What the defenders of the dunes ask, however, is: Do they have to do it there? In the middle of an irreplaceable natural treasure? Sound economic reasons make the dunes an ideal site for a steel mill. It adjoins the new Burns harbor where the ore boats can unload, it straddles main railroad arteries, and it lies in the heart of a rapidly expanding market for finished steel products.

They could have put it a couple of miles inland," Hawkinson insists. "They've got to load all that iron ore into railroad cars. It wouldn't cost them anything more to move it a couple of miles further." in this he is mistaken, however. Every extra foot would increase the steel companies' costs and worsen their competitive position. Some conservationists argue that the steel companies should have been willing to pay this price as a public responsibility, but corporation executives hesitate to put hard cash into nebulous causes. Stockholder suits have been instituted for more frivolous reasons than that. Corporations, moreover, vehemently deny that they ignore their public responsibilities. Bethlehem boasts that it is spending more than a million dollars to landscape its plant in the dunes. [In fact, it had to. After the ground cover was stripped off, the sand was blowing everywhere and damaging the machinery.]

In the struggle for Hawkinson's two acres, Bethlehem will eventually win, of course, and Hawkinson will lose. The rest of the forest will come down, and the beech, the maple, the oak, the gum trees will die. The indigo bunting will find another home. But Hawkinson will savor a more important victory: By clinging to his land until the end, he helps to persuade Bethlehem executives that they must not oppose the national lakeshore. When the lakeshore plan is realized, he can retreat from the field of battle, his honor still intact.

But he will have one personal loss to mourn. "I still love the place," he says. "That's what hurts."