Last updated: June 30, 2025

Person

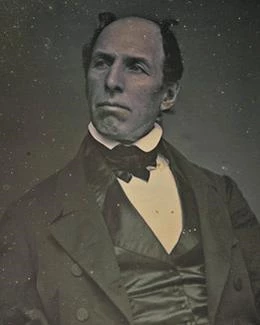

Francis Jackson

Digital Commonwealth

Boston businessman and reformer Francis Jackson served as Treasurer of the 1850 Boston Vigilance Committee.

Born in 1789, Francis Jackson grew up in Newton, Massachusetts. The son of a Revolutionary War veteran, Jackson, likewise, served his country at Fort Warren on Governor’s Island in Boston Harbor during the War of 1812. He eventually moved to Boston where he became a successful land agent and real estate broker. Jackson married Elizabeth Copeland in 1813 and soon began a family with her.1

In addition to his work and family life, Jackson participated in civic affairs and numerous reform movements. He held several municipal positions in Boston. He advocated for women’s rights and joined with Boston’s Black community in their efforts for equal schools. Jackson also worked in criminal reform and anti-capital punishment campaigns.2

In October 1835, Jackson witnessed the mob attack on abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and immediately joined the antislavery cause. From that day forth, he became Garrison's "ardent champion and patron." He even offered his home for the society's next meeting declaring that, despite the risk of another mob assault, his house could not "crumble in a better cause." "As slavery cannot exist with free discussion," he said, "so neither can liberty breathe without it."3

He served as a longtime president of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society and donated heavily to various antislavery endeavors. Referencing Jackson's lineage, Garrison said "In the veins of Mr. Jackson ran the best blood of the Revolution...the love of liberty, therefore, seemed to be inborn..."4

As a staunch and radical abolitionist, Jackson committed himself to helping freedom seekers escaping slavery on the Underground Railroad. In 1846, he served in Boston's second Vigilance Committee, a short-lived organization that assisted freedom seekers. He opened his home as "a haven of refuge to those flying slaves whom neither man befriended nor the law protected." Jackson's friend, Lydia Maria Child said, "It would not be easy to number the fugitive slaves he helped with his money and his counsel; and every friend of the slave found a welcome in his hospitable mansion."5

Although appointed Justice of the Peace for a time, Jackson publicly resigned in protest stating he could not take an oath to the Constitution given its fugitive slave clause. He wrote:

I will join in no slave hunt. My door shall stand open, as it has long stood, for the panting and trembling victim of the slave-hunter. When I shut it against him, may God shut the door of his mercy against me!6

Following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, Jackson joined the third and final iteration of the Boston Vigilance Committee. He served on the Finance Committee and as Treasurer of the organization. In addition to detailing the donations and expenditures of the committee, Jackson's Treasurer's account book provides a remarkable and unique window into Boston's Underground Railroad network. It lists freedom seekers by name, in many cases, as well as the various ways that the committee aided them on their journey to freedom. Like many Vigilance Committee members, Jackson donated generously to support the work of the organization.7

Jackson's support for freedom seekers continued even as he suffered from a long-term illness that ultimately took his life:

I cannot withhold my aid from fugitive slaves, who for the last twelve or fifteen years have had much of my time and assistance. I cannot deny them, while I have any strength left. They and the millions they have left are my system of Theology, my Religion, my Atonement...I believe the slaves are God’s chosen people.8

Just weeks before his death in 1861, he put out a call in the Liberator:

AID FOR FUGITIVE SLAVES. – the fund raised to aid fugitive slaves is now, and has been for some time, exhausted. Those who are disposed to contribute to this deserving charity are respectfully invited to leave their contributions with FRANCIS JACKSON, Hollis St., or R.F. Wallcut, at the Anti-Slavery Office.9

Prior to his death, Jackson made his wishes clear:

At my decease and burial, I desire that forms and ceremonies may be avoided, and all emblems of mourning and processions to the grave. Such irrational and wasteful customs rest on fashion or superstition; certainly, not on reason or common sense. The dead body is of no more consequence than the old clothes that covered it. Nothing should be wasted on the dead, when there is so much ignorance and suffering among the living.10

In keeping with this view, Jackson generously left money in his will for the causes important to him: ten thousand dollars "to create a public sentiment in favor of putting an end to negro slavery;" five thousand dollars to "secure the passage of laws granting women the right to vote;" and an additional two thousand dollars to "be used in aid of fugitive slaves."11

His remains are interred at East Parish Burying Ground in Newton, Massachusetts.12

Footnotes:

- "Francis Jackson," Find a Grave Memorial; In Memoriam. Testimonials to the Life and Character of the Late Francis Jackson, (Boston: R.F. Wallcut, 1861), 7, In Memoriam. Testimonials to the Life and Character of the Late Francis Jackson, Internet Archive; George Adams, Boston City Directory, 1850-1851, 200; The National Archives in Washington, DC; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M432; Residence Date: 1850; Home in 1850: Boston Ward 10, Suffolk, Massachusetts; Roll: 337; Page: 334a, Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. Original data: Town and City Clerks of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Vital and Town Records. Provo, UT: Holbrook Research Institute (Jay and Delene Holbrook).

- In Memoriam, 7; William Cooper Nell, Selected Writings: 1832-1874, Dorothy Porter Wellesley and Constance Porter Uzelac, eds. (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2002), 31, 265, 331-332.

- Henry Mayer, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), 208.

- Nell, Selected Writings, 153, 191; In Memoriam, 9.

- Dean Grodzins, "Constitution or No Constitution, Law or No Law: The Boston Vigilance Committees, 1841-1861," in Matthew Mason, Katheryn P. Viens, and Conrad Edick Wright, eds., Massachusetts and the Civil War: The Commonwealth and National Disunion (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015), 58; "Francis Jackson," Liberator, November 22, 1861; In Memoriam, 21-22.

- In Memorium, 31.

- "Members of the Committee of Vigilance," broadside printed by John Wilson, 1850, Massachusetts Historical Society; Austin Bearse, Remininscences of Fugitive Slave Law Days in Boston, (Boston: Warren Richardson, 1880), 4.

- Austin Bearse, Remininscences of Fugitive Slave Law Days in Boston, 17.

- "AID FOR FUGITIVE SLAVES," Liberator, October 18, 1861.

- In Memoriam, 3.

- In Memoriam, 35

- "Francis Jackson," Find a Grave Memorial.