The parks of the North Coast and Cascades Network (NCCN) are conducting or supporting research and monitoring projects to better inform park management and the public of the influence of changing climates on park ecosystems. Global evidence of changing climates is visible in species distributions, phenologic patterns, and forest mortality. Changes evident in NCCN park resources include tree establishment in subalpine meadows, severe flood events that remove entire roads or campgrounds, and losses in glacial mass of 50% since 1900. Climate models predict drier summers, wetter autumns, and decreased snowpack in the Pacific Northwest – leaving NCCN parks challenged to respond to climate disruptions in proactive ways that incorporate up-to-date research and knowledge of their specific resources, environment, and management.

Climate Change Monitoring Programs - North Coast Cascade Network Inventory and Monitoring

North Cascadia Adaptation Partnership - Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Strategies

High Mountain Lakes

Global climate change is expected to impact mountain lake systems. With over 1,500 mountain lakes in North Cascades, Mount Rainier, and Olympic National Parks, this key and treasured ecological resource is threatened by rapid and substantial increases in air and water temperature. At-risk are the timing and duration of ice cover and hydrologic regimes (e.g., snowmelt), potentially altering food web interactions, species diversity, and nutrient dynamics. To assess change, the North Coast and Cascades Network Inventory and Monitoring (NCCN I&M) Program monitors 20 high-elevation lakes to identify long-term trends in water quality, biological indicators, and lake physical characteristics.

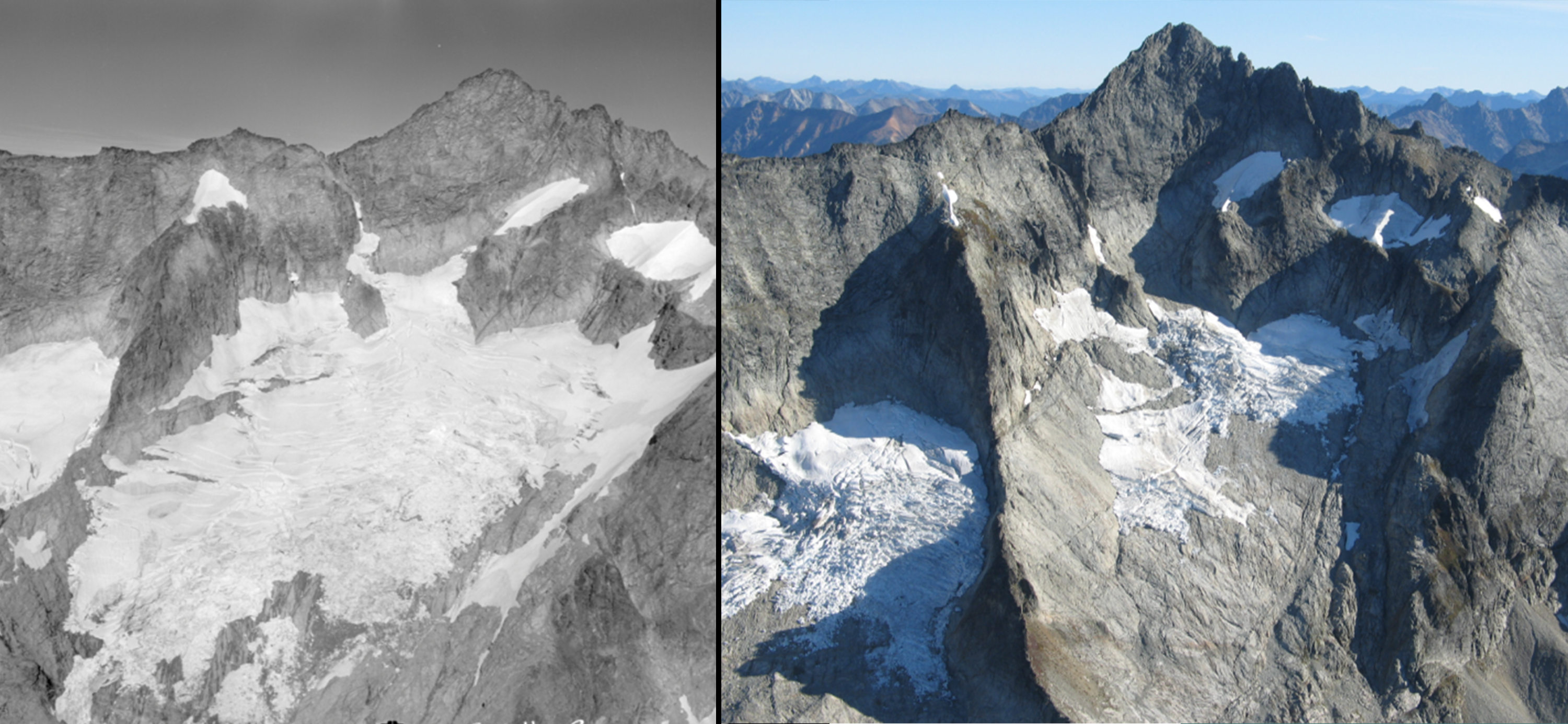

Glaciers

Glaciers, sensitive to seasonal variation in temperature and precipitation, are excellent indicators of regional and global climate. Covering a combined area of approximately 60,000 acres in North Cascades, Mount Rainier, and Olympic National Parks, glaciers have shaped each park’s dramatic scenery, topography, and landforms while providing billions of gallons of freshwater for drinking, irrigation, hydroelectricity, fishing, water-based recreation, and wildlife. With small mountain glaciers in rapid retreat in these parks, declining upwards of 50% in the last 100 years, the NCCN I&M Program monitors six “index” glaciers for yearly mass balance and summer meltwater discharge, and for ten-year glacier area/volume changes.

Old-growth Forests

Tree mortality in old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest is doubling every 17 years, most likely due to climatic shifts to warmer and drier conditions. The implications of which are fewer large trees, less carbon storage, forests predisposed to abrupt dieback, and habitat modifications affecting plant and animal composition and distribution. Of the old-growth forests that remain, the largest contiguous blocks persist in NCCN parks. To track the health of this iconic ecosystem, the NCCN I&M Program monitors trends in tree mortality, recruitment, and growth, and forest structure and composition, as it relates to climate change, in old-growth and mature forests of North Cascades, Olympic, and Mount Rainier National Parks, and Lewis and Clark National Historical Park.

Alpine Treeline Ecotone

Warmer temperatures, reduced snowpacks, and longer growing seasons are predicted to facilitate increased tree establishment in subalpine and alpine areas. As treeline rises, the location and composition of herbaceous communities will change, altering habitats for high-elevation vertebrates and pollinators. Earlier snowmelt may also allow low-elevation predators, such as coyotes, easier access to subalpine environments. Wetlands in the alpine treeline ecotone will face shorter hydro-periods resulting in changes to vertebrate, invertebrate, vascular and non-vascular communities. Species with low mobility such as pikas, heather voles, and endemic subalpine plants may not be able to move to suitable areas at the same rate as their preferred habitats retreat.

Invasive Non-native Species

The spread of invasive species is recognized as one of the major factors contributing to ecosystem change and instability throughout the world. The species have the ability to displace or eradicate native species, alter fire regimes, damage infrastructure, and threaten human livelihoods. There are more than 200 introduced, invasive species of plants, animals, and invertebrates in North Cascades National Park. The future accelerated rate of global climate change is likely to amplify the speed and magnitude at which invasive plants are currently displacing native species. Resource managers in North Cascades National Park conduct surveys to locate invasive species and quickly control or remove these populations. A few of the most problematic species are knotweed (Polygonum spp.), cheat grass (Bromus tectorum), Eastern brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis), and redside shiner (Richardsonius balteatus).

Whitebark Pine

Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) is a keystone species of high-elevation ecosystems in Western North America. It is often the first tree species to establish in subalpine meadows or on alpine ridges. Once present on a site, whitebark pine influences snowmelt patterns and soil development, and provides important micro-sites for the establishment of other subalpine plant species. Whitebark pine seeds are a valuable food source for birds, squirrels, and bears. The long-term survival of whitebark pine is threatened by an introduced fungus, white pine blister rust (Cronartium ribicola), and mountain pine beetles (Dendroctonus ponderosae). Scientists believe that warmer summer temperatures may allow both blister rust and beetles to spread more rapidly in whitebark pine populations, resulting in higher rates of mortality.

Coldwater Fish

Bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus) and westslope cutthroat (Oncorhynchus clarki lewisi) are important coldwater fish native to streams in North Cascades National Park. Warming temperatures will increasingly stress coldwater fish at several life history stages. Changes in water temperatures and flow regimes may eliminate many spawning areas and result in water temperatures lethal to adult fish. High water temperatures may allow non-native fish to increase in abundance or distribution causing changes in the trophic structure of aquatic ecosystems. High surface water temperatures may exacerbate pollution issues resulting in water quality degradation and changes in species compositions. Currently, genetically pure native westslope cutthroat are found in only the very upper reaches of the Stehekin River watershed. Increasing water temperature and changes in flow regimes will reduce habitat and may increase hybridization and competition with nonnative rainbow trout. The Upper Skagit watershed, meanwhile, supports the second largest bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus) population in the conterminous United States and provides one of the last remaining strongholds for bull trout in the Puget Sound Basin.