Courtesy of Gerald McWorter and Kate Williams McWorter Historical OverviewFrom a distance, New Philadelphia looked like a typical Illinois pioneer town of the mid-1800s. Villagers filled baskets with a bounty of apples, corn, and wheat. Farmers hitched mules and oxen to carts filled with vegetables, fruit, and grain to sell at markets. The hammer of a blacksmith rang as it shaped hot metal into shoes for mules and horses and other household necessities. Smoke from cooking fires and fireplaces swirled from the dwellings that dotted small plots of land.But New Philadelphia was not a typical pioneer town. As travelers got closer, they would find a small but bustling community where Black and White villagers lived and worked side by side. For formerly enslaved Free Frank McWorter, the town meant new beginnings and an opportunity to free family enslaved in Kentucky. New Philadelphia, which he founded in 1836, is the first US town platted and registered by an African American. New Philadelphia’s story begins in 1777 South Carolina with Frank’s birth to Juda, an enslaved West African woman. He spent the first 42 years of his life in bondage, and during that time moved to Kentucky with his enslaver in 1795. On the Kentucky frontier, Frank met his wife Lucy and together they started a family. In the time he was not required to work directly for his enslaver, his time and skills were hired out to other pioneers. This is a practice some enslavers allowed because they collected part of their earnings. In addition, Frank mined local caves for saltpeter, a component of gunpowder, vital for life on the frontier and in demand for the War of 1812. While Frank was known for his ingenuity and hard work, the opportunity to earn income was not an option for many enslaved people.

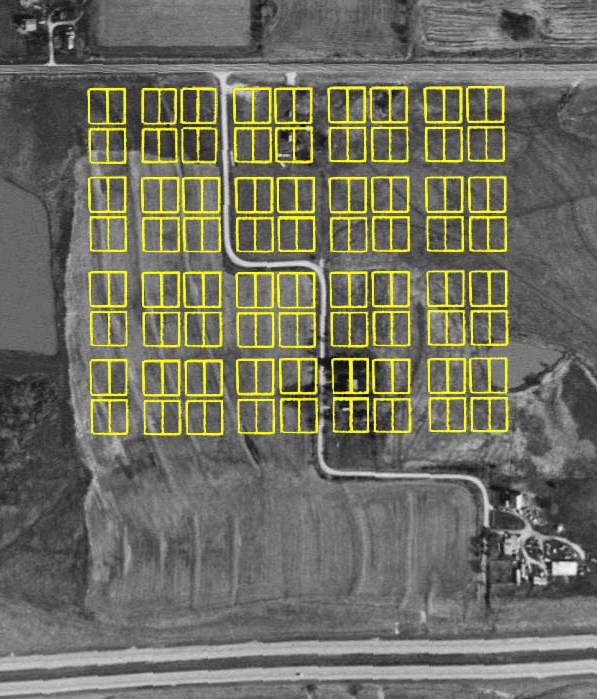

Courtesy Chris Fennell, Professor of Anthropology and Law, University of Illinois In 1835, Free Frank McWorter paid $100 for an eighty-acre parcel of land. He laid out the town he called Philadelphia on 42 acres of that land and platted the parcel into 144 lots. With this land Free Frank hoped to create a safe and affordable community for Black and White Americans. This philosophy proved successful and fostered a community that was prosperous with no reports of racial violence. The excerpt of an April 1998 aerial photograph on this page from the U.S. Geological Survey shows the landscape on which New Philadelphia was located. Approximate graphic depictions of the town lots and streets, as platted by Free Frank McWorter in 1836, have been overlain onto this aerial photo. Sources: U.S. Geological Survey, Aerial Photographs Collection; D. W. Ensign, Atlas Map of Pike County, Illinois, Davenport, Iowa: Andreas, Lyter & Co., 1872, p. 84, from 1976 Unigraph reprint; Pike County Deed Book, Vol. 9, p. 183 (1836). Find additonal maps.

Courtesy of Pamela and Sheena Franklin Due to its position near transportation routes and natural resources, New Philadelphia seemed primed for success. Federal census records from 1850 to 1880 report that residents worked as cabinetmakers, shoemakers, a wheelwright, a carpenter, a physician, teachers, ministers, merchants, and blacksmiths. The town served as a stagecoach stop and supported a post office for a time. Population estimates vary. In 1865, the town population hit its peak with as many as 100 residents. Thirty percent of town residents were Black. However, when a new railroad bypassed the town in 1869 and other communities developed nearby, the population began declining. By the end of World War II, many villagers had moved away in search of jobs and better economic opportunities. Only one family remained on the town site in the 1950s. Plows buried any material remains left behind, and grazing livestock and crops covered most of the site.

Courtesy of Paul A. Shackel, University of Maryland The site became a unit of the National Park Service in December 2022. The National Park Service will work to establish a presence at New Philadelphia National Historic Site to further elevate Free Frank McWorter’s life and legacy. New Philadelphia is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, designated as a National Historic Landmark, and included in the National Park Service’s National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. The story of the McWorters and New Philadelphia is included in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History’s ongoing exhibit, “Many Voices, One Nation.” Learn MoreNational Park Service Resources

Other Resources

Additional ReadingFennell, Christopher C. Broken Chains and Subverted Plans: Ethnicity, Race, and Commodities. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2017.LaRoche, Cheryl Janifer. Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance. Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2014. McCartney, Carol. Finding Home in New Philadelphia and Pike County, Illinois. Illinois: Pike County Historical Society and New Philadelphia Association, 2022. McWorter, Gerald A. and McWorter, Kate Williams. New Philadelphia. Path Press, 2018. Shackel, Paul A. New Philadelphia: An Archaeology of Race in the Heartland. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011. Walker, Juliet E.K. Free Frank: A Black Pioneer on the Antebellum Frontier. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1983. |

Last updated: September 11, 2023