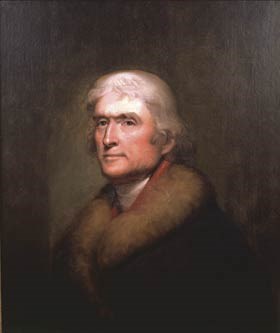

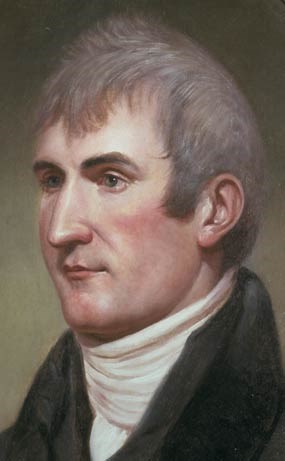

Thomas Jefferson was elected to the presidency in 1800. Two years later, he decided to organize an official, government-sponsored expedition to explore the upper reaches of the Missouri River and by so doing to find the elusive Northwest Passage to the Pacific Ocean. He chose Meriwether Lewis, his personal secretary, to lead the expedition. In January 1803, Lewis traveled to Philadelphia for intensive training with the leading American scientists, learning the use of scientific instruments, the rudiments of surveying, medicine, natural history and ethnology. In June 1803, Lewis asked William Clark, a friend from his former army service, to serve as co-leader of the expedition. Clark gladly agreed.

The Expedition BeginsIn December 1803, William Clark established “Camp Wood” at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, north of St. Louis. While there he recruited and trained men, while Lewis spent time in St. Louis, conferring with traders about the Upper Missouri regions and obtaining maps made by earlier explorers. On May 14, 1804, the Corps of Discovery left Camp Wood. The party numbered 45, and included 27 young, unmarried soldiers, a French-Indian interpreter, Clark’s slave, York, and Lewis’s Newfoundland dog, Seaman. An additional group of men would travel only to the Mandan country for the first winter, and these included six soldiers and several French boatmen.

Westward to the PacificOn April 7, 1805, Lewis and Clark sent the keelboat back to St. Louis with an extensive collection of zoological, botanical, and ethnological specimens as well as letters, reports, dispatches, and maps, and resumed their westward journey in two pirogues and six dugout canoes. The “corps of volunteers for the North Western Discovery,” now numbering 33, traveled into regions which had been explored and seen only by American Indians. By August 17 they reached the navigable limits of the Missouri River in the Rocky Mountains, and turned north up the Jefferson River. The expedition crossed the Continental Divide through Lemhi Pass, and purchased horses from the Shoshones, Sacagawea’s people. They traveled north to Lolo Pass where they crossed the Bitteroot Range on the Lolo Trail; this was the most difficult part of the journey. Lewis and Clark reached the country of the Nez Perce on the Clearwater River in Idaho, and left their horses for dugout canoes. From there they made their way down the Clearwater, Snake, and Columbia rivers, reaching the Pacific Ocean by November 1805. The Return JourneyThe return trip began on March 23, 1806. After a tough journey up the Columbia River against strong currents, the party retrieved their horses from the Nez Perce, and waited for the deep mountain snows to melt. After crossing the Bitteroots the party split at the Lolo Pass to add to the geographical knowledge they could gather. Confident of their survival, Lewis went north while Clark went south to the Yellowstone River. While on the Marias River, Lewis’s small party had a fight with a party of Piegan Blackfeet in which two Blackfeet were killed. This was the only violent incident of the entire journey. The Corps of Discovery was reunited in North Dakota, at the mouth of the Yellowstone River. They left Charbonneau and Sacagawea at the Mandan villages, continued down the Missouri River, and returned to St. Louis on September 23, 1806. The Importance of the JourneyThe results and accomplishments of the Lewis and Clark Expedition were extensive. It altered the imperial struggle for control of North America, particularly in the Pacific Northwest, by strengthening the U.S. claim to the areas now including the states of Oregon and Washington. Lewis and Clark achieved an impressive record of peaceful cooperation with the different tribes and generated American interest in the fur trade. This had a far-reaching effect, since it led to further exploration and commercial exploitation of the West. Lewis and Clark added to geographic knowledge by determining the true course of the Upper Missouri and its major tributaries, and producing important maps of these areas. They forever destroyed the dream of a Northwest Passage, but proved the success of overland travel to the Pacific. The expedition compiled the first general survey of life and material culture of the tribes they encountered. |

Last updated: September 16, 2020