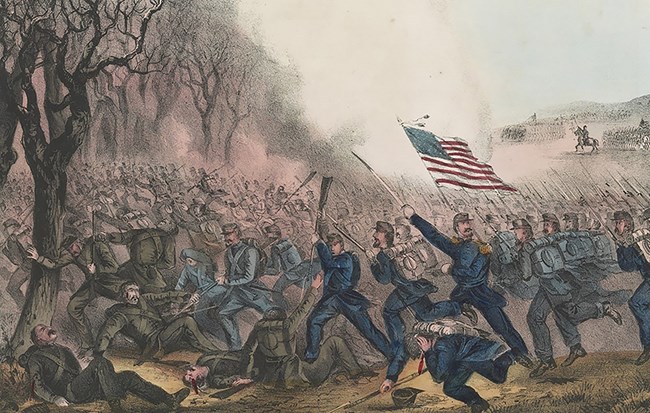

Library of Congress First Major US Victory in the WestOn January 19, 1862, through foggy and mired conditions, federals under Brigadier General George H. Thomas defeated Brigadier General George B. Crittenden's attacking confederate forces. The battle resulted in the US's first major victory in the Western Theater of the American Civil War and the death of Confederate General Felix K. Zollicoffer. The rout of the enemy was complete . . . They then threw away their arms and dispersed through the mountain byways in direction of Monticello, but are so completely demoralized that I don’t believe they will make a stand short of Tennessee.Dispatch from US Brig. Gen. George Thomas to US Maj. Gen. George McClellan

PreludeFollowing the events at Fort Sumter, Kentucky declared neutrality in May 1861. President Lincoln, acknowledging its strategic importance, accepted this decision. However, tensions rose as the war progressed. After Confederate General Polk occupied Columbus, Kentucky, the state swung pro-Union and joined the war in September 1861. Both sides then moved to secure positions and routes within the state. After several battles and skirmishes around the Cumberland Gap, Confederate General Zollicoffer established a camp at Beech Grove on the Cumberland River. Recognizing this as a threat, the Union sent General George Thomas to confront the position. As Thomas approached, Confederate General George Crittenden arrived at Beech Grove. Concerned about the impending attack and his own defenses, Crittenden decided to launch a preemptive strike. This set the stage for a crucial battle on Kentucky soil, known as the Battle of Mill Springs. The BattleIn hopes of surprising the sleeping Federals, the Confederates trudged through a dark, rain-soaked night but were spotted by Federal pickets. Exchanging fire, the Confederates slowly advanced, forcing the Federals back until confusion stopped them. Believing friendly fire was occurring, Confederate General Felix Zollicoffer rode forward to stop it. However, what he had thought to be Confederate soldiers were, in fact, Federals. His mistake cost him his life. The Confederate attack faltered, and with the outcome in the balance, General Crittenden was forced to assume command. |

Last updated: February 4, 2024