Last updated: June 10, 2025

Article

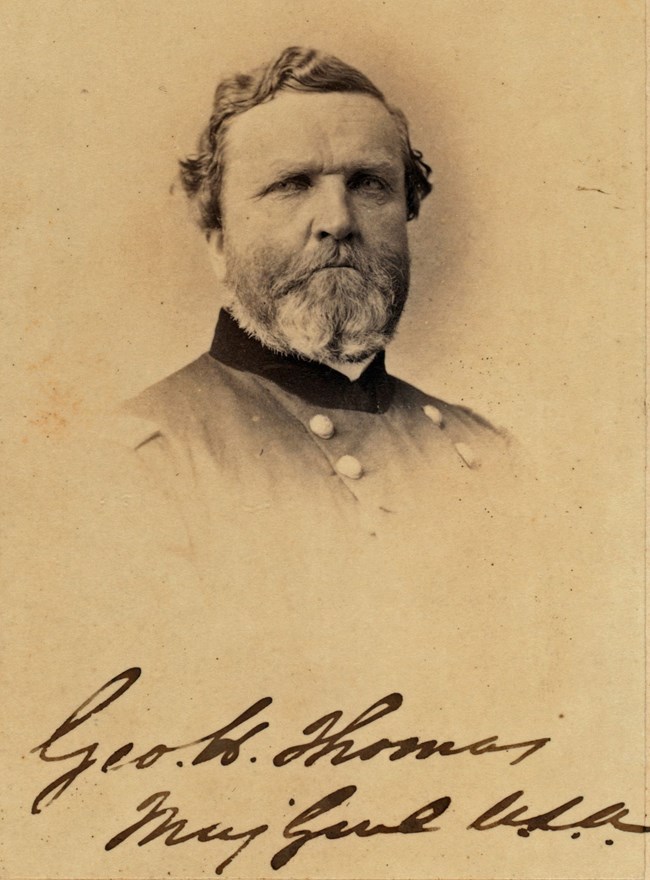

George Henry Thomas at the Battle of Mill Springs

Library of Congress

George Henry Thomas was born into a wealthy slaveholding family at Newsom’s Depot, Virginia, on July 31, 1816. Thomas’ father died from a farming accident in 1829 which left the family in financial troubles. Thomas’ views on slavery have been debated by historians for years. His family’s experiences during Nat Turner’s slave rebellion in 1831 may have impacted his dislike of slavery, however he nonetheless had slaves for a large portion of his life. Thomas was appointed to the Military Academy at West Point, graduating 12 out of 42. Appointed to the Artillery, Thomas served in the Mexican-American War under Braxton Bragg, who would later become his foe. After the Mexican-American War, he became an instructor of Cavalry and Artillery at West Point, and worked under the academy’s superintendent Robert E. Lee. When Virginia decided to secede, Thomas was forced to choose between his country and his state. He ultimately decided to remain loyal to the United States. He was then sent to Kentucky to organize troops at Camp Dick Robinson.

In November 1861, Confederate General Felix Kirk Zollicoffer moved north towards Monticello, Kentucky from Eastern Tennessee and began constructing winter encampments near Mill Springs on the northern and southern banks of the Cumberland River. On December 28, 1861, US Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell ordered Thomas to leave Lebanon, Kentucky and proceed towards Zollicoffer’s fortified camp at Beech Grove north of the river. Buell’s instructions were that the move must be made swiftly and in secret. Rainy winter weather compounded the roads that Thomas’s army had maneuvered on which would hinder any rapid movement.

On December 31st, Thomas’ men broke camp and began the march towards Logan’s Crossroads. He had two brigades: One commanded by Acting Brigadier General Mahlon Manson (10th Indiana, 4th Kentucky, 10th Kentucky, and 14th Ohio), and the other commanded by Acting Brigadier General Robert L. McCook (2nd Minnesota, 9th Ohio, 18th US, 35th Ohio). The 35th Ohio Infantry was in Somerset with Brigadier General Albin Schoepf and Acting Brigadier General Samuel P. Carter. The 18th US Infantry was not prepared to march and would remain in Lebanon.

Delayed in Campbellsville, Kentucky for five days organizing and refitting, Thomas’ brigades were again marching on January 7th 1862. The weather they encountered was very bad, with rain making the roads almost impassible. Soldiers wrote that the wagon wheels cut the roads up, making the mud up to eight inches deep in some places. Thomas reached Columbia, Kentucky, on the 9th, and his brigades began heading east towards Somerset.

On January 12th, Thomas’ column only covered 6 miles and went into camp near Webb’s Cross Roads. Here, Thomas’ two brigades were joined by four companies of Frank Wolford’s 1st Kentucky Cavalry Regiment (A, B, C & H). The next day, they covered less than five miles. Thomas camped near Goose Creek on the night of the 13th, and stayed there until the morning of the 15th before the column resumed their march. Thomas appraised Buell that the roads were the worst he had ever seen. The bedraggled column finally reached Logan’s Crossroads on January 17th. Thomas established his headquarters and his men went into camp as they arrived.

On the morning of January 19th, Confederate troops left their winter encampment at Beech Grove and engaged Federal pickets from the 1st Kentucky Cavalry regiment at around 6:10 A.M. The Confederate force would continue to push federal pickets back, meeting more resistance as they advanced. The 10th Indiana Infantry and 1st Kentucky Cavalry successfully delayed the Confederate advance long enough to alert the rest of the federal troop in the area.

Although surprised that the Confederates would come out from their entrenchments to attack him, General Thomas displayed a cool head and ordered many of the men not currently engaged to form a defensive line. Thomas arrived at the front shortly after Zollicoffer was killed. He quickly surveyed the situation and decided that the place where his troops were currently engaged would be a good spot to put up a fight, and ordered McCook’s brigade up to the front. Thomas’ left flank held off several Confederate attacks on their position, eventually forcing the Confederates to retreat. His right pushed the Confederates from the field with a bayonet charge. Thomas would order his men to pursue the enemy all the way back to Beech Grove, at which point he would have his artillery shell the Confederate camp until dark.

At daybreak the next morning, Thomas ordered the 10th Kentucky and the 14th Ohio into the Confederate camp, only to find that it was abandoned during the night. The Confederate army had used a steamboat to retreat and burned the boat after the crossing was complete. With no means of crossing the Cumberland River, Thomas could not pursue the retreating Confederates. When a boat was finally brought down, Thomas crossed the river and set up temporary headquarters at the Brown House near Mill Springs where he wrote his report of the recent battle which became the common name of the battle.

General Thomas would go on to win acclaim fighting in battles throughout the western theater of the American Civil War such as Stones River, Chickamauga, and Nashville. He gained nicknames such as “The Rock of Chickamauga” and “The Sledge of Nashville”. By the end of the war, Thomas was revered by the men he commanded and respected by the men he fought. He gained a reputation for slow, deliberate, and well-planned movements which many times brought him at odds with his superiors. Thomas continued in military service, commanding the Department of the Cumberland through 1869 and leading the fight against the campaign of terror and intimidation of the newly formed Ku Klux Klan. In 1869, Thomas was transferred to San Francisco to command the Division of the Pacific. He died there from a stroke on March 28, 1870, and was buried in his wife's hometown of Troy, New York with full military honors.

Thomas would never achieve the level of fame enjoyed by his contemporaries, in part because he wrote no memoirs and instructed his wife to burn his personal and military papers after his death.

Bibliography

Hafendorfer, Kenneth A., Mill Springs: Campaign and Battle of Mill Springs, Kentucky (KH Press, 2001).

Wills, Brian S., George Henry Thomas: As True as Steel (University Press of Kansas, 2019).

United States War Department., The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. (Government Printing Office, 1894).