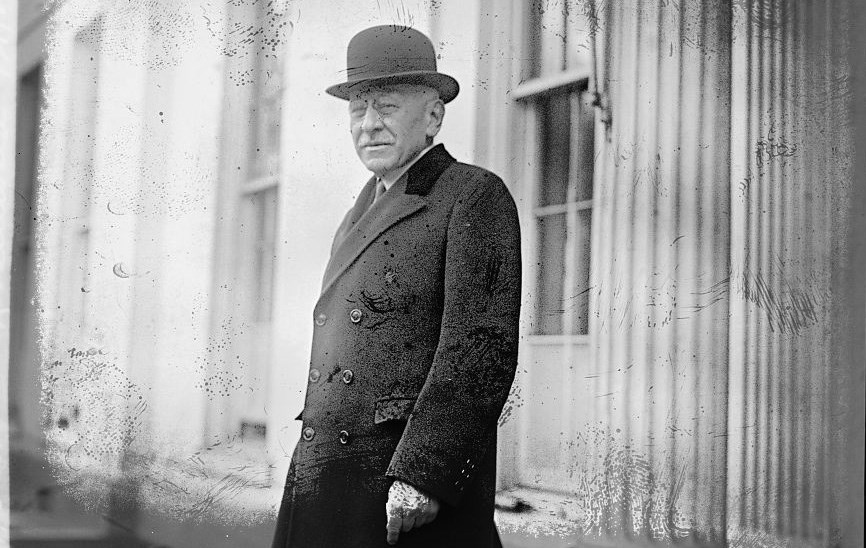

Library of Congress Julius Rosenwald, one of the most important and socially impactful sons of Springfield, Illinois, is also one of the least known. The man who grew up in the shadow of Abraham Lincoln became the president of Sears, Roebuck and Company, eventually amassing a fortune, most of which he dedicated to helping those who faced the injustices of a racially divided America.

NPS SpringfieldJulius Rosenwald was born in Springfield, Illinois on August 12, 1862, while Abraham Lincoln was president of the United States, in a home on Seventh Street only a block away from the Lincoln family home. Seven years later, the Rosenwalds moved to a home on Eighth Street across from Lincoln’s home. The house is now part of Lincoln Home National Historic Site.

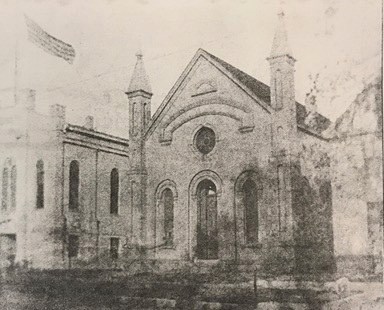

Sangamon Valley Collection, Lincoln Library By 1867, despite being relatively new to the area, Samuel Rosenwald served as president of the family’s Jewish place of worship, congregation B’rith Sholom. Julius Rosenwald later recalled his Jewish upbringing: “I may lay claim to being deeply consecrated to the Jewish faith because not only was I Bar Mitzvah at thirteen, but it so happened that a year later, our congregation in Springfield, Illinois, dedicated a new Reform temple with confirmation exercises, and I was also confirmed...”

Library of Congress Rosenwald attended Springfield’s Fourth Ward public school and then attended Springfield High School but dropped out when he was seventeen to work as an apprentice at his uncle’s New York City wholesale clothing company. Rosenwald remained in the wholesale clothing business in New York and Chicago for the next 16 years. It was in Chicago that Rosenwald met Augusta “Gussie” Nusbaum and they were married in 1890. In 1895, Rosenwald and his brother-in-law Aaron Nusbaum each invested $37,500 in cash in Sears & Roebuck—and Rosenwald’s career took off. Julius Rosenwald and Sears, Roebuck & CompanyRosenwald rose quickly in the Sears, Roebuck and Company organization, reaching the position of vice president in 1896 and president in 1908. Rosenwald is credited as the person who identified and implemented the management and business strategies that resulted in the phenomenal growth of Sears. With its exclusive line of dry goods, consumer durables, hardware, furniture, and farm equipment and its pioneering catalog marketing, Sears sold its products across the nation. From 1895 to 1907, catalog inventory increased and annual revenues skyrocketed from $750,00 to $5 million.

Library of Congress Julius Rosenwald, PhilanthropistRosenwald’s business success earned him what he said was more money than he could ever spend and he determined to engage in a philosophy of civic stewardship. His generosity received national attention when, on this fiftieth birthday in 1912, he gave away nearly $700,000, approximately $18 million today, to a variety of organizations. Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch, or Chicago’s Temple Sinai where Rosenwald attended, had a major influence on Rosenwald’s philanthropy. Hirsch once stated, “Property entails duties. Charity is not a voluntary concession on the part of the well-situated. It is a right to which the less fortunate are entitled in justice.” Rosenwald left an incredible mark on countless charities, cultural institutions and social causes throughout Chicago and the United States. Among them was the forerunner of the Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago, where he was a founder and an early chairman of the board. Rosenwald created the Rosenwald Fund in 1917 to professionally manage his philanthropy with a “Give While You Live” approach; he put his wealth into the causes and projects he believed in while he was alive. Rosenwald opposed the creation of permanent trusts and the Rosenwald Fund closed sixteen years after its benefactor’s death. Rosenwald has been called “America’s First Social Philanthropist.” Over his lifetime, he contributed more than $60 million, approximately $1 billion today, through his personal and foundation giving.

Wikimedia Commons, Photographer Andrew Jameson Rosenwald YMCAsMore than half of Rosenwald’s philanthropic efforts benefited African Americans and these efforts began with his support of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCAs) facilities. YMCAs could be found in white communities across America but YMCAs in African American communities often lacked the resources of their white counterparts. The YMCA approached Rosenwald in 1910 with a proposal to build a new location in Chicago. He agreed, but only if a facility for African Americans was also constructed. “I won’t give a cent to this $350,000 fund,” Rosenwald told the group, “unless you will include in it the building of a Colored Men’s YMCA.” The YMCA agreed, and opened the Wabash Avenue YMCA in 1913. Chicago’s Wabash Avenue YMCA, situated in the city’s historic Bronzeville District, thrived as a center of civic and social activity for the city’s burgeoning African American community. It was there in 1915 that historian Carter G. Woodson founded “The Association for The Study of Negro Life and History,” responsible for establishing Negro History Week which eventually evolved into what is now celebrated nationally as Black History Month. With the success of the Chicago effort, Rosenwald offered matching challenge grants to other sites around the country. Any city that raised $75,000 for the construction of a YMCA for African Americans would receive a $25,000 match. From 1911 to 1933, Rosenwald provided over $600,000 for the construction of twenty-five YMCAs for African Americans in twenty-four cities throughout the U.S.

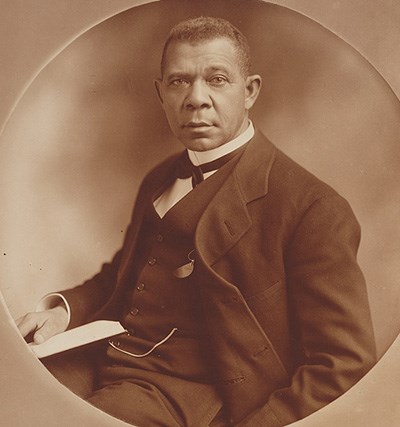

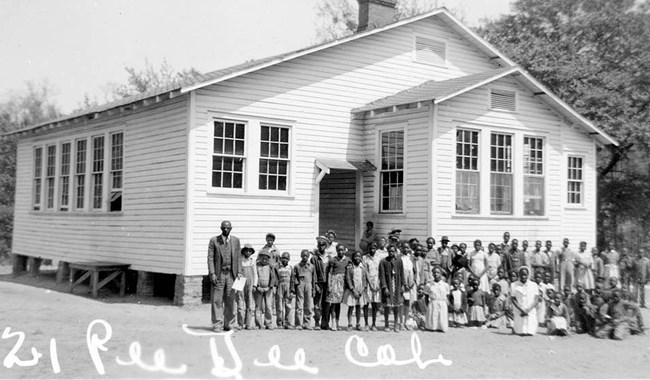

Library of Congress Rosenwald SchoolsThe United States Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson “separate but equal” ruling reinforced the “separate” segregationist life in America but in most cases the “equal” part of the ruling was lacking. This was especially apparent in the south where African American public schools were substandard compared to white public schools. In some areas no efforts were made to provide public schools for African Americans even though they were not allowed to attend white schools. Inspired by Tuskegee Institute founder and first president Booker T. Washington’s efforts to provide quality education for African Americans, Julius Rosenwald donated millions of dollars to build schools for African American children in the rural south. Rosenwald’s first exposure to Washington came in 1910 when Rosenwald read Washington’s autobiography Up from Slavery. The two met for the first time at a fundraising event the following year hosted by Rosenwald at Chicago’s Blackstone Hotel, at which Washington was the featured speaker. Rosenwald began assisting with the construction of schools in 1913.

South Carolina Department of Archives and History Most of what came to be known as “Rosenwald Schools,” were designed by architects at Tuskegee Institute. Rosenwald Schools were a sign of progress and a source of pride in African American communities. Rosenwald provided funding for schools but required resourced to be contributed by the local African American community as well as by local tax funds. From 1917 to 1932, more than five thousand Rosenwald schools were built in African American communities in fifteen states. During the 1920s, one in five schools for African Americans in the rural South was a Rosenwald school. By the time the last school was built in 1932, more than 600,000 African American children in the south had attended a Rosenwald school.

Fisk University, John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library Special Collection, Julius Rosenwald Fund Archives

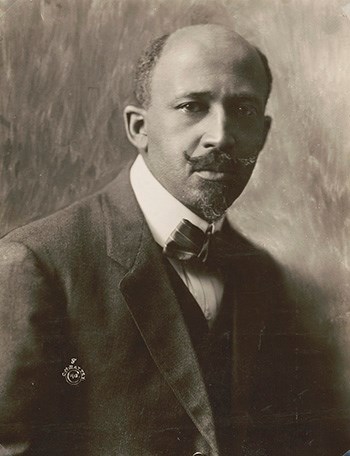

Library of Congress Rosenwald FellowshipsThe start of what would be called Rosenwald Fellowships happened when Ernest Just, a professor of biology at Harvard University who, largely because of racial discrimination, was unable to secure sufficient funding for his pioneering studies in cell biology. Beginning in 1920 and for the next 10 years, Rosenwald funded Professor Just’s research with grants of $2,000 per year. This was essentially the first of many Rosenwald Fellowships granted primarily to African American artists, writers, musicians, and academicians who could not otherwise afford to pursue their research, literary and artistic endeavors. Between 1928 and 1948, the Rosenwald Fund distributed millions of dollars in fellowship awards. Famous recipients include author W.E.B. Dubois, poet Langston Hughes, Historian John Hope Franklin and opera singer Marian Anderson. Rosenwald and the Museum of Science and IndustryRosenwald played a key role in the founding of Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry. Inspired by a 1911 visit to a museum in Munich, Germany, dedicated to industry and science, Rosenwald pledged $3 million toward the development of a like institution in Chicago, challenging other Chicagoans to also donate. In 1929, work began to convert the long empty former “Palace of Fine Arts” building, originally built for the city’s 1893 “World’s Columbian Exposition,” into the museum. Eventually, Rosenwald donated many millions of dollars toward the development of the museum, which open in 1933. Although he declined to have the museum named for him, during its early years it was commonly known among Chicagoans as the Rosenwald Museum.

Library of Congress

Flickr, photographer Eric Allix Rogers Michigan Boulevard Garden Apartments, Rosenwald Courts, ChicagoOne of Rosenwald’s business ventures was the Michigan Boulevard Garden Apartments, or Rosenwald Courts, an affordable housing development. Completed in 1928, this mixed-use project had more than 421 housing units, which provided affordable and modern housing in Chicago’s African American south side. Designed by Rosenwald’s nephew, Ernest Grunsfeld, the complex featured blond brick exterior and modernist lines that were inspired by European social housing projects. This style of public housing projects would soon be repeated across the country a decade later during the construction of public housing projects in the 1930s. Many noteworthy residents called Rosenwald Courts home including Nat King Cole, Duke Ellington, Quincy Jones, Joe Lewis and Jesse Owens. LegacyJulius Rosenwald’s diverse humanitarian legacy is unfortunately largely unknown today. His practice of keeping his name off the projects he funded, as well as his refusal to endow perpetual trusts to keep his name in the spotlight long after his death, contribute to his near obscurity. His business acumen helped create a retail revolution through his leadership of Sears, Roebuck & Company, while his generous investment in people, particularly African Americans, made a lasting impact on the country in the early 20th century and beyond. |

Last updated: October 8, 2023