Library of Congress

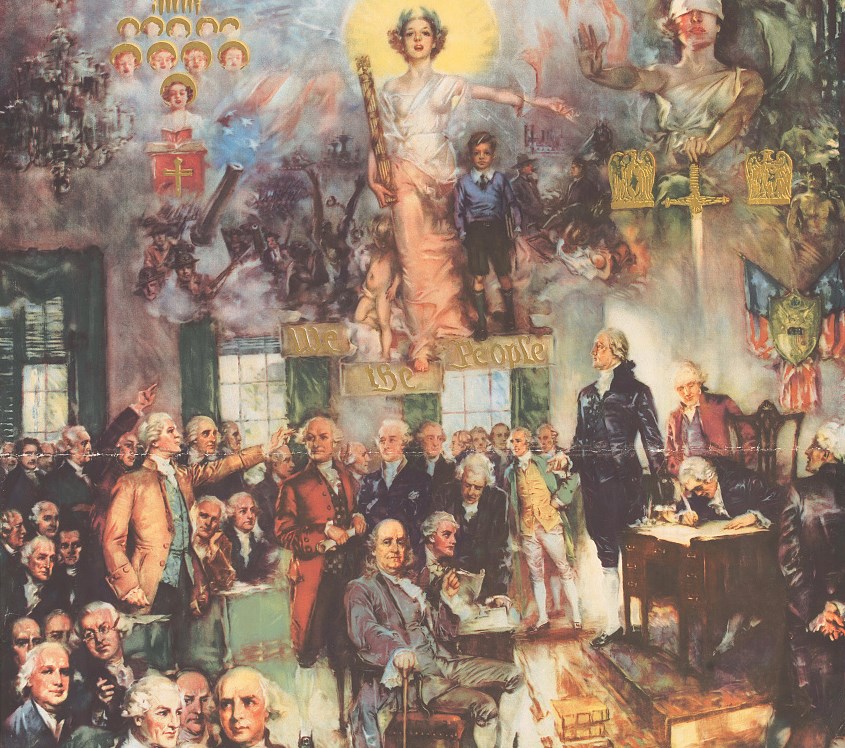

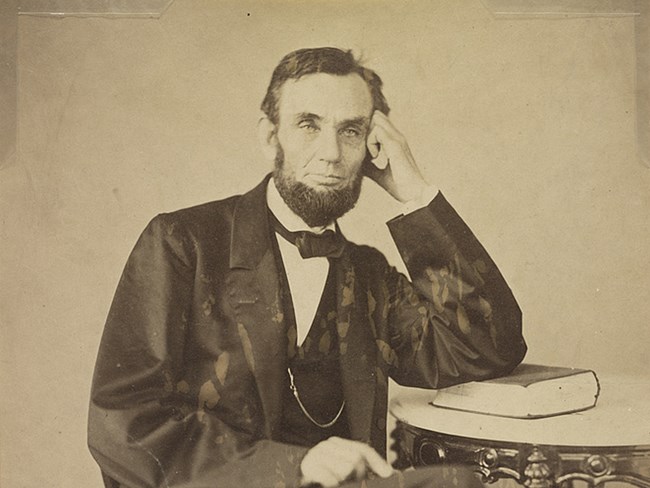

Library of Congress Slavery and SecessionDuring Abraham Lincoln’s early political career, he stated that he was not an abolitionist and believed that the United States Constitution protected slavery where it already existed. But, he also believed that the Founding Fathers had paved the way for the ultimate extinction of slavery by preventing its spread to new territories. Habeas CorpusOne of the most controversial things Lincoln did while he was President involved the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus: a Constitutional guarantee of one’s right to take legal action against unlawful detention.

Library of Congress In Lincoln's WordsAbraham Lincoln held the utmost respect for the Constitution, and believed that any of his controversial actions in relation to the Constitution were necessary for the preservation of the Union during the extraordinary times of the Civil War. Throughout his career he spoke of the importance of the Constitution. Freedom for the Slaves

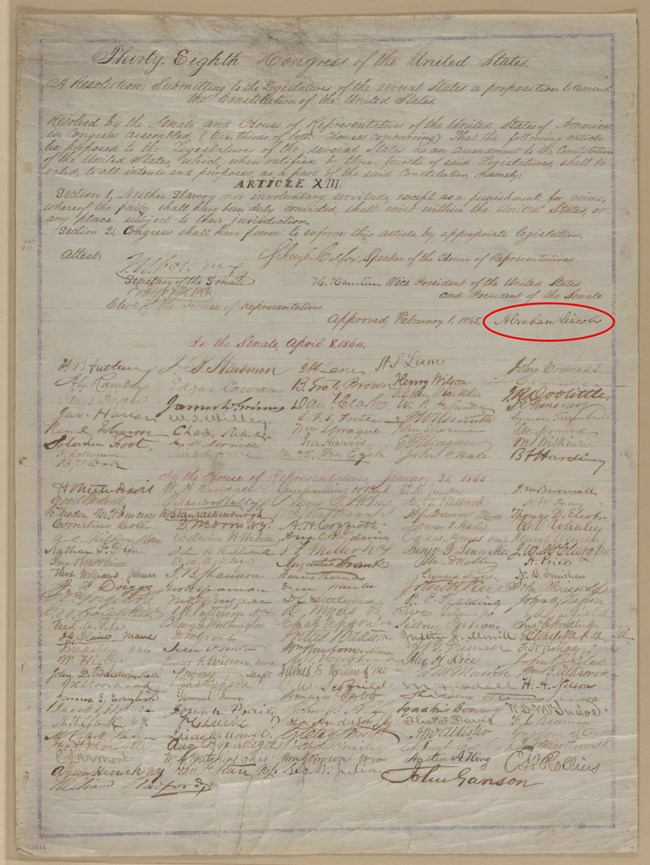

Library of Congress Emancipation ProclamationPresident Lincoln issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, and then on January 1, 1863, issued the official Emancipation Proclamation declaring freedom for the slaves in ten Confederate states. Lincoln, anticipating backlash challenging his authority on the matter, issued the Executive Order by his authority as “Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy,” cited under Article II, Section 2 of the United States Constitution. The Thirteenth AmendmentAbraham Lincoln feared that the Emancipation Proclamation would be regarded as merely a temporary war measure and may not be honored after the end of the Civil War. To permanently abolish slavery in the United States, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was proposed on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865. Though the amendment was not ratified until after his death in April 1865, President Lincoln enthusiastically added his signature to the Congressional resolution passed on February 1, 1865. The Fourteenth AmendmentWith the Emancipation Proclamation and Thirteenth Amendment, President Lincoln initiated a course of events that would eventually lead to the Constitutional protection of equal rights for former slaves. The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified on July 9, 1868, ensured that all former slaves were granted automatic United States citizenship and that they would have all of the rights and privileges enjoyed by any other citizen. The Fifteenth AmendmentLoopholes in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments were exploited by those wanting to limit the liberties of newly-freed slaves. In an attempt to close these loopholes, Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution on February 26, 1869. The amendment, which was ratified on February 3, 1870, specified that United States citizens could not be denied the right to vote based on “race, color, or previous conditions of servitude.” References Eric Foner, Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction (2006)Michael Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, The Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment (2001) Mary E. Neely, Jr., The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (1992) William Whiting, The War Powers of the President (1864), available on the Library of Congress website (www.loc.gov) The National Constitution Center: www.constitutioncenter.org/lincoln |

Last updated: January 13, 2026