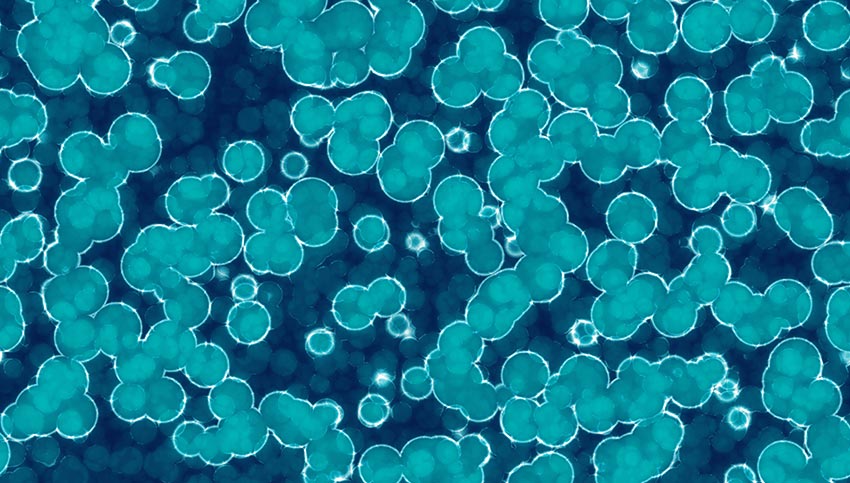

An algal bloom near the shore. Doctors evaluate human health by asking questions about how we are feeling, using stethoscopes, taking x-rays, and by using other tools and tests. In the same way, scientists determine the health of natural systems by observing both the health of the organisms that inhabit them and the well-being of the system as a whole. In addition to examining the fish, snails, and other species living in the water, a lake’s physical condition is evaluated by measuring characteristics like temperature, dissolved oxygen level, nutrients (such as phosphorus and nitrogen), and water pH. An important component of a lake’s health is its photosynthetic organisms – the primary food and oxygen producers such as algae. Which species of algae are present, where they are, and how many there are depends on a variety of factors including available nutrients, water temperature and movement, and even wind. Generally speaking, Lake Mead and Lake Mohave are typically low in nutrients, but nutrient levels are always changing. Tributaries such as the Las Vegas Wash, Virgin River, Muddy River and the Colorado River are not only adding water to the system, but nutrients as well. Both Lake Mead and Lake Mohave experienced algal blooms in the early 2000s. Since then, the wastewater treatment plants along Las Vegas Wash have enhanced their phosphorus removal1, improving water quality and reducing the potential for algae blooms. Also researchers have recently been closely monitoring algae, including being on the lookout for a type of algae called blue-green algae. One type of blue-green algae, called microcystis, had periods of high numbers from 2011-2015. The high numbers of algae themselves aren’t necessarily a problem but the toxin they can produce is. This toxin is called microcystin and it affects people’s liver when ingested and can cause skin and nasal irritations from water contact. Microcystin also has the potential to be fatal to pets and livestock. In the spring and summer of 2015, both Lake Mead and Lake Mohave experienced notable concentrations of blue-green algae. The detection of algal toxins in 2015 triggered algal bloom advisories for various locations across the lakes. Both water and wind move the blooms to new areas, so pinpointing locations is difficult. While no significant blue-green algae concentrations occurred and no algal toxins were detected, Lake Mead National Recreation Area continues to advise lake visitors to look for green or yellow streaks on the surface (or just below the surface) of the water and avoid contact.

Blue-green algae (microsystis) produce toxins and must be closely monitored for. Climate change may affect algae by increasing growth rates, extending distribution and prolonging survival. The invasive quagga mussel may also affect lake ecosystems in ways that can enhance populations of blue-green algae. However, creating models of algal blooms is complicated and has been difficult for scientists to predict where and when blooms might happen. References

|

Last updated: April 4, 2017