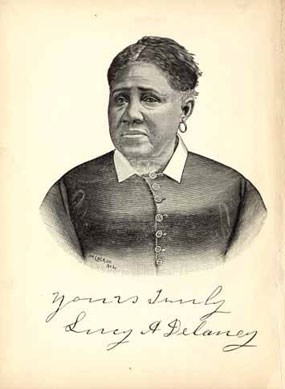

The case of a woman named Lucy Delaney is interesting to us today for several reasons. The case involves several of the ways by which slaves took action for themselves and tried to gain their freedom. Lucy’s father was sold down the river to work on a plantation in the deep south when Lucy was a young girl. Her mother, Polly Wash, escaped from St. Louis on the Underground Railroad, although she was captured and returned. She had been freed in a will, and had also lived in free territory, but was later kidnapped and returned to slavery. Polly sued in a court of law for her freedom and won her case. She then helped her older daughter Nancy, who was being held in bondage by another master, to escape to Canada on the Underground Railroad, and Lucy to sue for her freedom based on the principle of “partus sequitor ventrum,” literally, Latin for "what is born follows the womb." In other words, if the mother of a slave was declared to be a free person, and was legally free at the time of a child’s birth, the child was also, by law, entitled to their freedom. The Lucy Delaney case is striking because it is based on this point of law – and because it is so hard – almost impossible – for us to imagine a 17-year-old girl being kept in prison for a year and a half, having committed no crime except the fact that she was born with black skin, the daughter of a slave. Lucy Delaney wrote a book about her life in 1892 called From the Darkness Cometh the Light. It is the only direct account we have of what it felt like to be a slave suing for your freedom in the St. Louis courts. Lucy recorded that "I was put in a cell, under lock and key, and remained for seventeen long and dreary months, listening to the 'foreign echoes from the street...'" Lucy was incarcerated in the St. Louis County jail by her owners, David D. Mitchell and his wife, because they felt that she was a flight risk, and that, like her older sister Nancy, she might run away to Canada. For this reason Lucy was not even hired out during the pendency of her suit. An existing record from the St. Louis Circuit Court provides information about Lucy's incarceration: Dec. 13, 1842 - the said petitioner by her attorney...files her petition...setting forth among other things that she is confined in the jail of St. Louis County, and that she is suffering from a severe Cold occasioned as she believes from a deficiency of clothing and the dampness of the room in which she is Confined, and that had it not been for the careful attention of her mother who visited her frequently her sufferings would have been incalculable, and she believes that death would have been the Consequence of such Cruelty...[T]he Court doth order the jailer to inquire into her condition as to lodging and clothing and make report thereof...without delay." Although the jailer made an inspection, he reported to the court the following day that Lucy was "well clothed and comfortably lodged," a rather unbelievable claim considering the swiftness of the supposed change. Three years later, a slave named Eliza and her infant daughter lay near death in the St. Louis jail, due to the long term of their incarceration and the inability of the Sheriff to hire them out, and a continued stay in jail was reported by the sheriff to be potentially "fatal to one or both of them." Lucy recalled sitting in the court room in the Old Courthouse: On the 7th of February, 1844, the suit for my freedom began. A bright, sunny day, . . . but my heart was full of bitterness; I could see only gloom which seemed to deepen and gather closer to me as I neared the courtroom.... After the evidence from both sides was all in, Mr. Mitchell's lawyer, Thomas Hutchinson, commenced to plead. For one hour, he talked so bitterly against me and against my being in possession of my liberty that I was trembling . . . , for I certainly thought everybody must believe him; indeed I almost believed the dreadful things he said, myself, and as I listened I closed my eyes with sickening dread, for I could just see myself floating down the river, and my heart-throbs of the mighty engine which propelled me from my mother and freedom forever! Lucy felt better as her own attorney, Edward Bates, summed up her side of the case. She had to wait until the following morning for the verdict. "All night long I suffered agonies of fright, the suspense was something awful." At last the courthouse was reached and I had taken my seat in such a condition of helpless terror that I could not tell one person from another. Friends and foes were as one, and vainly did I try to distinguish them. My long confinement, burdened with harrowing anxiety, the sleepless night I had just spent, the unaccountable absence of my mother, had brought me to an indescribable condition... Some other business occupied the attention of the Court, and when I had begun to think they had forgotten all about me, Judge Bates arose and said calmly, "Your Honor, I desire to have this girl, Lucy A. Berry, discharged before going into any other business." Judge Mullanphy answered "Certainly!" Then the verdict was called for and rendered, and the jurymen resumed their places. Mr. Mitchell's lawyer jumped up and exclaimed: "Your Honor, my client demands that this girl be remanded to jail. He does not consider that the case has had a fair trial . . . " Judge Bates was on his feet in a second and cried: "For shame! is it not enough that this girl has been deprived of her liberty for a year and a half, that you still pursue her after a fair and impartial trial before a jury...I demand that she be set at liberty at once!" "I agree with Judge Bates," responded Judge Mullanphy, "and the girl may go!" . . . I could have kissed the feet of my deliverers, but I was too full to express my thanks, but with a voice trembling with tears I tried to thank Judge Bates for all his kindness. After the trial Lucy’s mother traveled to Canada to locate her other daughter Nancy, who had escaped from slavery on the Underground Railroad. Polly found her living in Toronto, where she had married a prosperous African-American farmer and had several children of her own. Polly returned to St. Louis and lived with her daughter Lucy until her death. In 1845 Lucy married a man named Frederick Turner, and they moved to Quincy, Illinois, where Lucy made her living as a seamstress. Her husband was killed in the explosion of a steamboat named, ironically, the Edward Bates. Lucy remembered her mother’s words following her husband’s death: “Cast your burden on the Lord. My husband, and your father, is down south and may be dead. Your husband, honey, is in heaven, and mine – God only knows where he is!” By 1850 Lucy had moved back to St. Louis and married Zachariah Delaney, a boatman born in Ohio. The 1850 U.S. Census lists “Zachariah Delany” aged 28, Lucy A. Delany, aged 24, and their child, Charles Delaney, “¼” (meaning that he was three months old), in St. Louis’ 5th Ward. All were listed as mulattoes. Lucy tells us in her autobiography that eventually the couple had four children. In 1878, when the Exoduster movement started and former slaves left the South to start new lives in the American West, Lucy, aged 52, met her father once again. She mentioned that she had not seen him in 45 years, and that he was old, bent, grizzled and gray. Her mother was dead by that time, so he never got to see his wife again. He passed through St. Louis and settled in Kansas. Lucy served as the head of several women’s clubs, including one for the Masons and one for the Grand Army of the Republic. In 1892 she wrote her autobiography From the Darkness Cometh the Light; or Struggles for Freedom.

|

Last updated: April 10, 2015