I had my kids late in life, so even though I am on the far side of sixty, as recently as last year my daughter wore a costume and went Trick-or-Treating with her friends. During October, many people’s thoughts turn to scary things, and there is plenty of that in this month’s night sky.

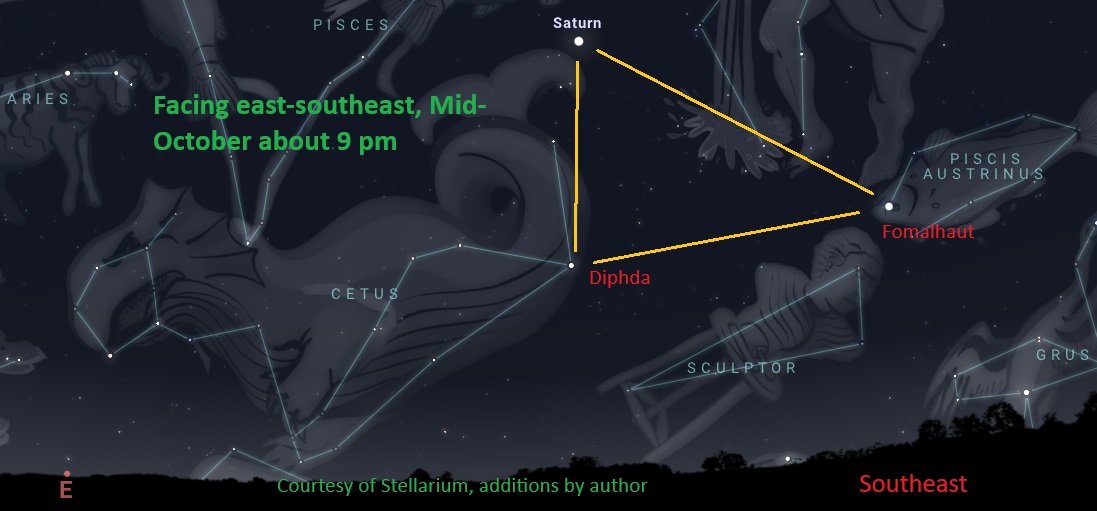

Let’s start by finding Saturn, which has finally broken the drought of evening planets visible in the sky. It is the only relatively bright “star” seen fairly low in the east to southeast in the early evening this month, rising higher and heading south as the hours and weeks pass. With a good telescope, Saturn’s rings look like a thin line this year, because we are seeing them nearly edge on. If it is a good clear night, you will notice two dimmer stars that form a triangle with Saturn - Fomalhaut and Diphda. Diphda is the brightest star in the mostly dim constellation of Cetus, the Sea Monster, sometimes also called a whale. According to the Stellarium map shown below, Diphda marks the point where the fearsome monster’s tail joins the body. The stars forming the head, well to the north (left) of Diphda, are a bit brighter than most of the rest and form a fairly distinct pentagonal shape. The rest of the constellation is quite dim and you will need to either bring out binoculars or head to a darker location if you live in a light-polluted location.

Cetus is a central part of the famous “Perseus Myth.” Queen Cassiopeia boasted that her daughter Andromeda was more beautiful than the Nereids, who often accompanied Poseidon (Neptune to the Romans), God of the Sea. They prevailed on him to chain Andromeda to some rocks and send Cetus to devour her. Perseus (see map below) came on the scene just in the nick of time, as heroes are wont to do, riding on the back of Pegasus, the winged horse. On the way to this potentially gory scene, Perseus had to slay the Medusa - a dangerous task as one look could turn anyone to stone. He used a shiny shield so as to not directly look at her while wielding his mighty sword. Very wisely, Perseus kept the Medusa’s head handy - you never know when it might be useful. Think how useful having a Medusa could be if you are on the road or if someone is trying to get ahead of you in line. The hero made short work of the monster by showing the Medusa to Cetus, thereby turning it to stone. Naturally, Perseus and Andromeda fell in love and lived happily ever after. Our hero did find the Medusa to be useful once again when some of her Andromeda’s suitors showed up and tried to disrupt their wedding. Perseus, Cassiopeia, King Cepheus, Andromeda, Pegasus, and Cetus have all been placed in the sky to recall this perhaps most famous of all star myths.

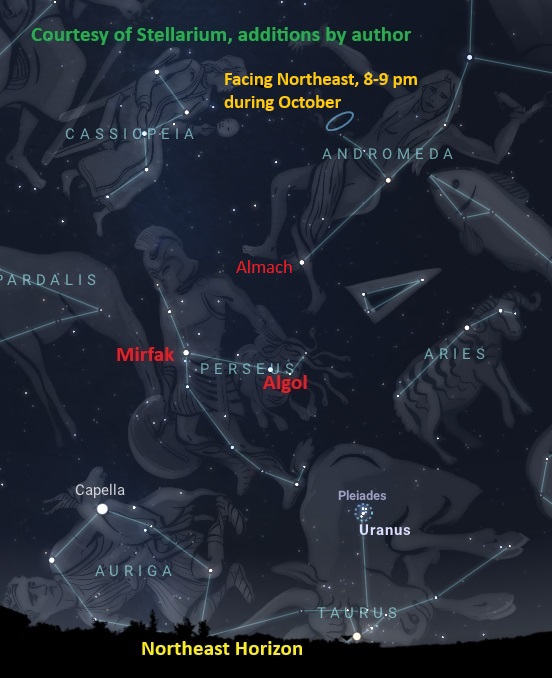

The star Algol is usually the second brightest star in the constellation Perseus. It is normally slightly dimmer than nearby Mirfak and about equal to Almach. The best way to find Perseus is to locate the distinct “W” or “M” shape that marks the stars of Cassiopeia, currently high up in the northeastern sky, and look straight down from there at this time of year. Every 2 days, 21 hours, Algol drops by about three quarters in brightness, to about equal to the dim star just above the “o” in its name in the map above. From my home about 20 miles from downtown St. Louis, when high enough in the sky, on a good clear night Algol is easy to see with the unaided eye when at normal brightness. At minimum, it can be hard to see with the unaided eye, and binoculars can help.

Although it is not certain, astronomers believe that the ancients noticed that there was something spooky about Algol, as it was considered “Satan’s Head” in Hebrew folklore, part of a mausoleum of stars to the Chinese, and “Head of the Ogre (Ghoul) to the Arabs. To the Greeks it may have been the winking eye of the decapitated Medusa. Algol is currently popularly known as the “Demon Star.” The cause of this fading was not determined until 1881, when astronomer Edward Charles Pickering announced that Algol was actually an eclipsing binary star, with a dimmer star obscuring a brighter one. There is also a very tiny eclipse when the brighter star covers the dimmer, but the change is so tiny that it takes instruments to measure.

If you just randomly look at Algol, there is about a one in thirty chance that you will see it significantly dimmer than normal, but here are some suggested times to watch, courtesy of Sky & Telescope magazine: November 7 6:01 pm, November 24 10:55 PM, Nov. 27 7:44 pm, Nov. 30 4:33 pm, Dec. 15 12:38 am, Dec. 17 9:28 pm, Dec. 20 6:17 pm. Start watching about 4 hours before the listed time, checking about every half hour or so to catch the fading. Algol will be at minimum brightness for about one hour on either side of the time, with the re-brightening taking about another 2-3 hours after the minimum. I have been watching Algol off and on for many years, and it is always fun to peek at it to see where it is in its cycle.

If all of this weren’t enough there is a chance that we may have a fairly bright comet visible in the evening skies of the second half of October. Should it look like Comet Lemmon will put on a good show worthy of interest by the general public, I may put out a special edition of this blog or post observing hints on our Park’s social media pages.

Fittingly enough with this scary theme, our last Gateway to the Stars event for 2025 will feature the traditional “Ghosts of the Arch Grounds” ranger talk. Learn about the various “incarnations” of the Arch Grounds as they evolved from a colonial village to a thriving riverfront to the present Gateway Arch National Park, with a great deal of adventure and tragedy involved. The “Ghost” talk will take place on our Entrance Plaza at 6:30 pm on Sunday, October 26, with telescope viewing on the Plaza to follow until 8:30 pm. In the event of inclement weather, the telescope viewing will be cancelled, while the talk will be moved just inside the Arch Main Entrance. In this case there will be no access to the downstairs Museum, Arch Store, or tram ride to the top. Call 314-655-1704 on the afternoon of October 26 in order to check on the status of the event.