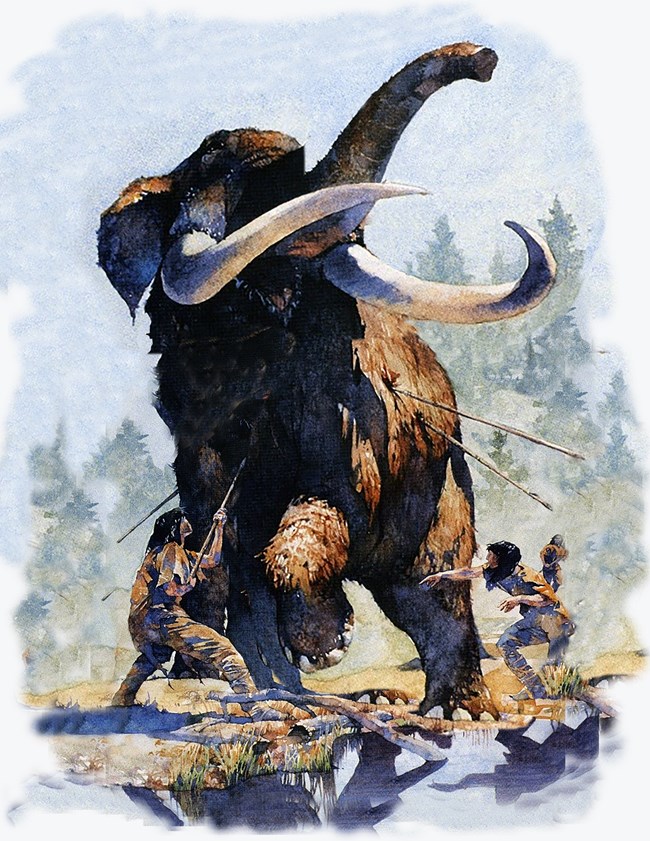

NPS Paleo and Archaic Cultures of Great Sand Dunes

NPS/Patrick Myers Culturally Modified Trees

NPS/Patrick Myers A Living Connection: Great Sand Dunes' Affiliated Tribes

NPS Archives Exploration and Settlement around Great Sand Dunes |

Last updated: May 1, 2025